Anne Helen Petersen on Scandals of Classic Hollywood

For most of us, celebrity gossip is a pastime. For Anne Helen Petersen, a staff writer at Buzzfeed and the author of Scandals of Classic Hollywood, it’s an academic pursuit. Petersen earned a PhD from the University of Texas specializing in the history of the gossip industry, and the ways that reporting on the stars reflects the cultural standards of the time. In her book, stemmed partially from a series of columns for The Hairpin, Petersen examines the lessons that celebrity scandals can teach us about “what it meant to be a man, a woman, a child, a straight person, a fat person, a person of color, or a sex object during specific time periods in our past.” Scandal, Petersen argues, is instructive because it necessarily instructs us about the status quo. Below, our conversation with Petersen about image management, movie stars, and what thing Beyonce does poorly.

What was it like shifting from academic writing to internet column writing to book writing?

I started blogging in 2007, at a site called Celebrity Gossip, Academic Style. It was a way to write about these concepts that I was reading about for my thesis but apply them to things going on at the time. I was also super lonely, you know, just reading theory books all the time. So the blog posts I wrote in a way that my mom could understand, rather than working in academese, which I was really sick of. And the day I turned in my dissertation, I had all this extra energy, and turned in a draft of what would be my first column for The Hairpin too.

What did you leave out of the book that you wish you could include?

I would have loved to do Joan Crawford and Bette Davis as tough broads. But the problems is both of them had careers that were so long and varied, they would have to be 50 page chapters. Those are two of my favorite stars of all time.

You had already done so much research in this area. What did you find that suprised you?

One of the interesting things is that as much as I knew about these stars and their images, I hadn’t done the nitty-gritty about how they were mediated by the fan magazines. Until very recently you couldn’t do that research. There are only a couple places that have those archives. People didn’t collect fan magazine because they were essentially looked at as trash. But this place, the Media History Digital Library, took the digitized backlogs and put those online. I didn’t have this with my dissertation in 2011 and it completely fleshed out so many stories. Having all of them available and researchable allowed me to do much more with the topics.

Why do you think celebrity gossip is so maligned as a topic?

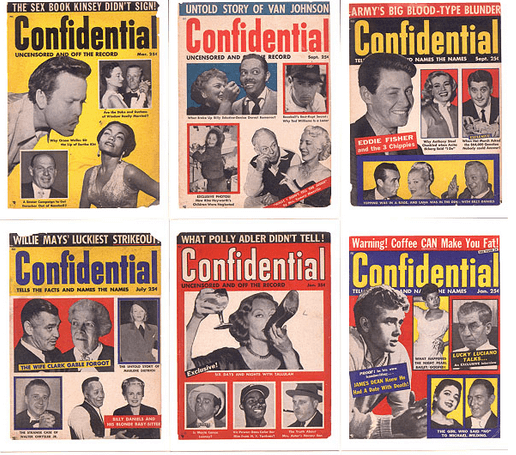

There’s two things. The fan magazines have always been incredibly feminized. Women’s culture is thought of as throwaway pleasures. Hard news is masculine and real intelligence, where this is fluff and soft and not worthwhile. Which is, of course, not true. Those magazines are incredibly instructive about the cultural moment. I mean, Us Weekly is a treasure trove for generations to come. I have my own personal archive of Us Weekly. The other reason is about sex. Things that address sex in an explicit or titillating way are delegitimized. Like, Confidential magazine was absolutely not collected because that was a real rag. You couldn’t even admit you brought it in the house.

One of the things I found so interesting about your book is how much the cycle of scandal has stayed the same, even though we like to think of ourselves as much more sophisticated than, say, audiences in 1917.

My favorite trope of the classic fan magazine is the phrase they used. “Has [insert name] gone high hat? It means: “Has this person become a snob? “We have very similar ways of framing the same question. That star, they’re too good. They think that they’re better than other people. That’s a small point but it’s one of many many things about how cyclical these things are. It’s all about regulating social behavior.

But I think it’s really easy to belive that every single reader believes exactly what they read in the fan magazines. In fact, that’s only a handful of people. There are people who are dubious, and then people who are kind of conspiracy theorists. There are people who believe that it’s gospel, and game players who try to figure out what’s really going on.

The difference between now and then is that if you were arguing with your friend you didn’t have proof that, say, Marlene Dietrich was making out was women. But there were things between the lines you could pick up. I’m writing now about Anna May Wong, the first Chinese-American movie star, and there were these items saying “Anna May Wong and Marlene Dietrich sure are really good friends.” You could pick up a Saphhic rumor from those pieces. But you had to know about it to see it.

How has social media changed the dynamic that we have with celebrities?

I think we view social media as this authentic conduit to the real star. Which is bullshit, of course. Maybe at the very beginning that was true. That time Ashton Kutcher tweeted a picture of Demi Moore’s butt. But there’s this carefully managed concept that Twitter is some sort of Wild West for stars, and I think that’s very rarely true. In some ways stars have usurped the paparazzi by using social media. Tabloids won’t get paid as much to get an exclusive of my baby if I post it first, that kind of thing. Every star has a very savvy social media team. Things that look staged or managed are really carefully elided. I mean, there might be a scandal if something accidentally went up, like a tweet that was meant to be a direct message. But everyone is so media trained now that odds of that happening are so small.

Right, it’s this weird game where celebrities are hyper-controlling of their image but have to appear to be casual about it.

Right! Like with the footage of Solange attacking Jay Z. What they did afterwards was so clearly managing, and there was backlash. Beyonce is very controlling and smart about day-to-day managing her image, but less smart when things go wrong. What you really want to do is instead of trying to manage the actual event, you change the conversation. When Brad Pitt and Angelina Jolie got together, they made the conversation be about their global philanthropy. If you chose to gossip about them—they were in Somalia and Tibet, helping children—you look like the asshole.

What do you think is scandalous now that won’t be in fifty years?

We like to believe that being gay is no longer an issue. Names don’t matter, but so I’m almost 100 percent positive that several major stars we have now are closeted. Not more than a handful, but still. It’s hard to drastically change your image one you’ve already gotten to a certain stage. Those people will be held up later as evidence of the persistence of the closet. The new generation of stars hardly bothers with being closeted. If you come out at 18 you make it as part of your image or you do something like Ellen Page and make it a non-announcement.

But there’s no fixed line on what is scandal. Something can be scandalous for one person and totally innocuous for someone else. Those nude photos that leaked of Jennifer Lawrence were not a scandal about her, it was about privacy and the photos. How would that affect Taylor Swift’s image differently? What’s interesting now is that the real way way to burn your image to the ground is to be really explicitly racist or homophobic. Those are things that wouldn’t have mattered as much, but now, career arsenic.

The thing about celebrity scandal is it’s rupturing the status quo. Because it’s something that’s societally binding. When there’s a rupture it takes all of this discourse and puts it out in the open. It really depends on the cultural moment. Sometimes scandal is a wedge driver and sometimes it’s papered over and nothing changes. The reason why it catches people’s eye because its challenging the way things are, and how we think they should be.

Anne Helen Petersen is launching Scandals of Classic Hollywood tomorrow at Powerhouse Arena, and you should go!

You might also like