Truman Capote’s Brooklyn Heights

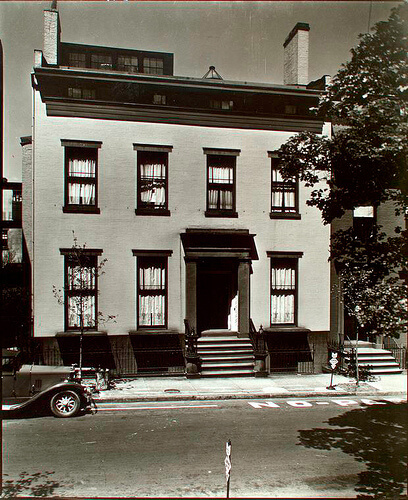

The brick house where Turman Capote lived in Brooklyn Heights.

“I live in Brooklyn. By Choice,” Truman Capote began his essay “A House in the Heights,” a response to why the complicated, charming, silver-tongued author with roots in Alabama chose to settle in the then decidedly unfashionable borough for a time. In the constant maelstrom of real estate speculation in Brooklyn, the wave currently crashing over Crown Heights and Bushwick, the borough’s conversion to a land of organic grocers and oyster happy hours seems inevitable. But when Capote settled in Brooklyn Heights in 1955, Brooklyn wasn’t a place that seemed on the verge of redemption. It was a place of quaint ruin, full of decaying mansions, a place that it was very difficult to convince fashionable people to come visit on the subway. Capote thought of his neighborhood and Brooklyn, fondly, as a lost cause.

Capote lived in a the basement of a yellow brick house at Willow Street, owned by his friend, Broadway stage designer Oliver Smith.There he entertained his cat and worked on the literature that would become his best: In Cold Blood, and Breakfast at Tiffany‘s. He was living here when he was still on relatively good terms with New York society, before the facelift, before the Black and White Party, before running himself into ruin. He was still young, then, fresh and hopeful, writing about the mysteries of New York City life, of art, of navigating foreign social land.

It’s the kind of house that seems impossible these days: high ceilings, twenty-eight rooms, marble-manteled fireplaces, situated in the tangle of charmingly named fruit streets in a pocket of Brooklyn Heights. When I walked past it on a recent blustery day, the softly glowing windows afforded a glimpse at a tastefully curated living room. A man on the corner walked a horse-sized dog. Sandwiched between brownstones and taller buildings on the block, the house looks like a single snaggly yellow tooth in a jack-o-lantern smile. Capote left the place in 1965, beginning his long slow decline into alcoholism and drug use. It sold in 2012 for $12 million, making it the most expensive single-family home sold in Brooklyn.

The picture Capote gives of his Brooklyn neighborhood is of a place that is in the midst of the Robert Moses-led urban renewal. “As a group, Brooklynites form a persecuted minority,” Capote wrote. Brooklyn has become “synonymous with the crudest, most vulgar aspects of contemporary life.” As for Brooklyn Heights:

It is condemned, of course; even now a tunnel is coming through, a highway is planned; steel-teethed machines are eating at its palisades, many of the old mansions wait in derelict darkness for the demolition crew; the red newness of Danger! Men Working signs glitter in the sober shade of dwarfed Dickensian streets: Cranberry, Pineapple, Willow, Middagh….as for Brooklyn, archaelogists of another civilization, like taxi drivers of our own, will never decipher the secret of its streets, their destination, their meaning.

It is a beautiful description, but it doesn’t exactly glimmer with prescience about the shape of the borough in fifty years. Capotes vacated the house in 1965. He died in 1984 in California, having run through his fortune and friends, just 59 years old. But one of the things that Capote captures about Brooklyn that hasn’t shifted in the decades since he occupied the little yellow brick house is Brooklyn as a place with a distinct melange of personalities, a crazy quilt of neighborhoods that each contain something precious. It is the poetry of the place that Capote understood and captured, the romance of being adjacent to blustery Manhattan, the scrappy kid brother of the glamorous jet set. In his essay, “Brooklyn”, Capote put it best:

Terribly funny, yes, but Brooklyn is also sad brutal provincial lonesome human silent sprawling raucous lost passionate subtle bitter immature innocent perverse tender mysterious, a place where Crane and Whitman found poems, a mythical dominion against whose shore the Coney Island sea laps a wintry lament.

You might also like