The Best Uzbeki Food in Brooklyn Is in This Woman’s Home

Last Sunday in Borough Park, I sat around the dining room table of Damira, a cardiologist from Uzbekistan. In front of us was a feast: cinnamon bread made from an Uzbek family recipe, a Georgian pastry filled with a tangy farm cheese, a bowl of crystalized sugar made from grape juice that, in Uzbekistan, is an aphrodisiac eaten on wedding days, and yet another traditional baked-dough pocket filled with vegetables and cheese.

“Usually, dinner or lunch begins with pastries like you see on this table,” Chef Damira tells me and four other guests from around Brooklyn. Damira, sitting at the head of her table, wore an Uzbek-style head scarf, and a traditional silk ikat; modern Uzbek music played in the background and pictures of her family rested on a table behind us. “And then,” Damira continued, “we eat again, but before, almost every time, we put sweet things on the table, in order for our life to be sweet.”

In addition to the sugary spread, hot tea inside a pot covered in blue and white cotton-flowers rested next to her. Green tea is traditionally served in Uzbekistan for strength, Damira told us, even during hot months. “It makes us fresh,” she explains. As we gobbled the sweets, Damira demonstrated the traditional way that Uzbek people serve their green tea. She took one small cup and poured it half full of steaming liquid—then she dumped it right back into where it came from.

“Now we say it is mud,” Damira said of its return to the pot. Then she did it again—another half cup, another pour back into the pot. “Now it will be wine,” she explained. And then, a final half-pour. “Now,” she finished, “it is tea.”

The first cup she poured for herself, “to make sure my pot I am giving to you is served with love,” she explained. “You see, I didn’t put the whole cup because it will sooner be cool.” This ensured more hot sips. And, “This means I respect my guests,” she continued. “If I give it to you cold, it means you have to get out.” We laughed: all of us had nice steaming cups of green tea. We got to stay and keep eating.

Damira had come from Uzbekistan with her husband, a historian, two years earlier. They moved into their apartment in Borough Park, with their son, who had found it for them. She and her husband wanted to try something new in retirement; the world is big, and we only get to be here one time. After telling us a bit more about Uzbek culture—handicrafts, like the ikat she wore—history, and the religious tolerance there, she explained how it was she came to be cooking her country’s traditional food for us that day.

When she first arrived to New York, she thought she might work in a hospital, like she did in Uzbekistan. But quickly, she changed her mind. She wanted to enjoy her life in retirement. “So I asked myself what I like to do. And I said I like to cook, and I like to have people around the table, to socialize with them, to tell them stories, and maybe they tell me interesting stories,” she explained. She researched some options and, eventually, a friend directed her to The League of Kitchens: This was the job she wanted. “I wrote my resumé and they invited me to interview. I started in December, and all the months I am working with great pleasure. Every time it is very interesting, and it is like the first time,” she told us, though we were about to make and eat recipes that she had made for herself and family and friends countless times, on the other side of the globe.

League of Kitchen’s founder and CEO Lisa Gross was raised on her Korean grandmother’s delicious cooking, but her grandmother had never allowed her to help—studying was more important, she insisted. But as Gross got older and tried to replicate her grandmother’s recipes, she failed. Something tasted different. Whatever her grandmother was doing could not be learned from a recipe. To make the staple Korean dishes—and matzoh ball soup (she is also half Jewish)—Gross realized she needed her grandmother’s—or someone else’s grandmother’s—expertise, to learn the hands-on preparation and process beyond the recipe. Only this could replicate the food she had eaten growing up.

Beyond nourishment, what those recipes contained was family history, passed from mother to daughter, on and on. What Gross ate from her grandmothers were not just perfect dumplings; she was eating an entire family tree of tradition and love. And that, above all, can not be incorporated into a dish when directed in two dimensions, from a recipe.

And so Gross set out to gather expert grandmothers from around the world, living in New York City, who could fill the role of her grandmother, and teach her and other New Yorkers authentic, long-held recipes but, along with it, stories of culture, history and family, inside of these expert home cooks kitchens. Today, Gross and League of Kitchens have assembled home cook instructors from Japan, Argentina, Trinidad, Greece, Bangladesh, Lebanon, Afghanistan, and India. Their immersive, five-plus hour home cooking lessons have grown so popular that Stephen Colbert got in on the fun: At Chef Yamani’s home in Queens, he prepared a multiple course Indian feast, grilling naan over the stove top, breaking coconuts with a hammer, and slinging knives.

And on Sunday, we got invited to do the same—only with Uzbek food—with Chef Damira inside her home kitchen in Borough Park.

All five of Damira’s students had varying degrees of cooking experience. For most, myself included, experience was limited, save for one student whose Jamaican family had taught her that food was the cure for everything. The rest of us were, above all, eager students who really liked to eat. “I love people who love to eat,” Damira said, as we finished our pre-meal sweets and then walked into our classroom, the kitchen.

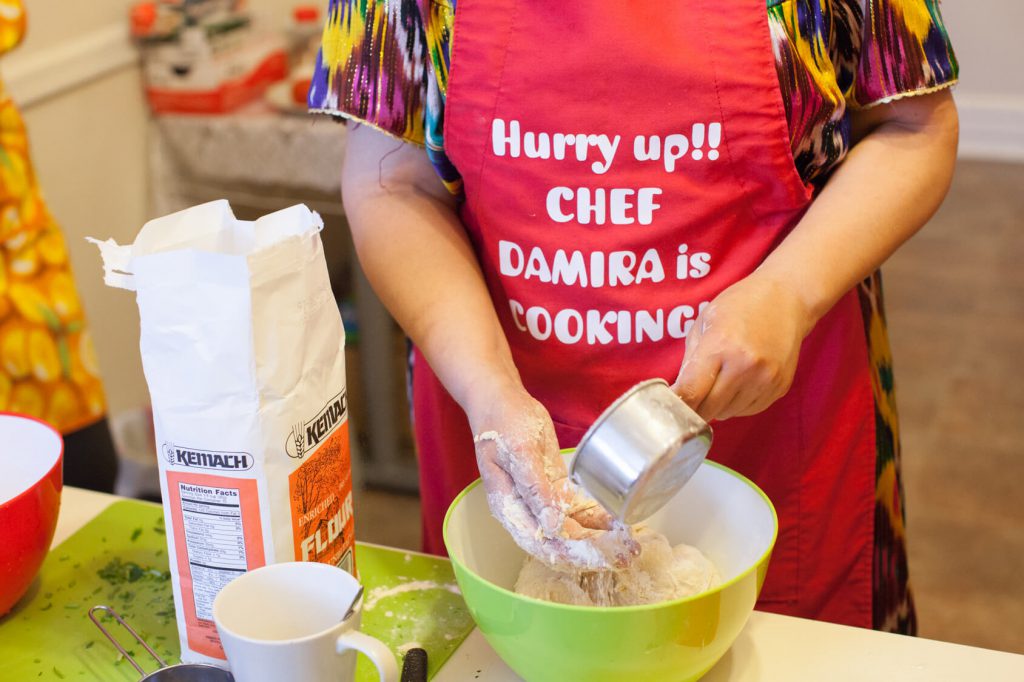

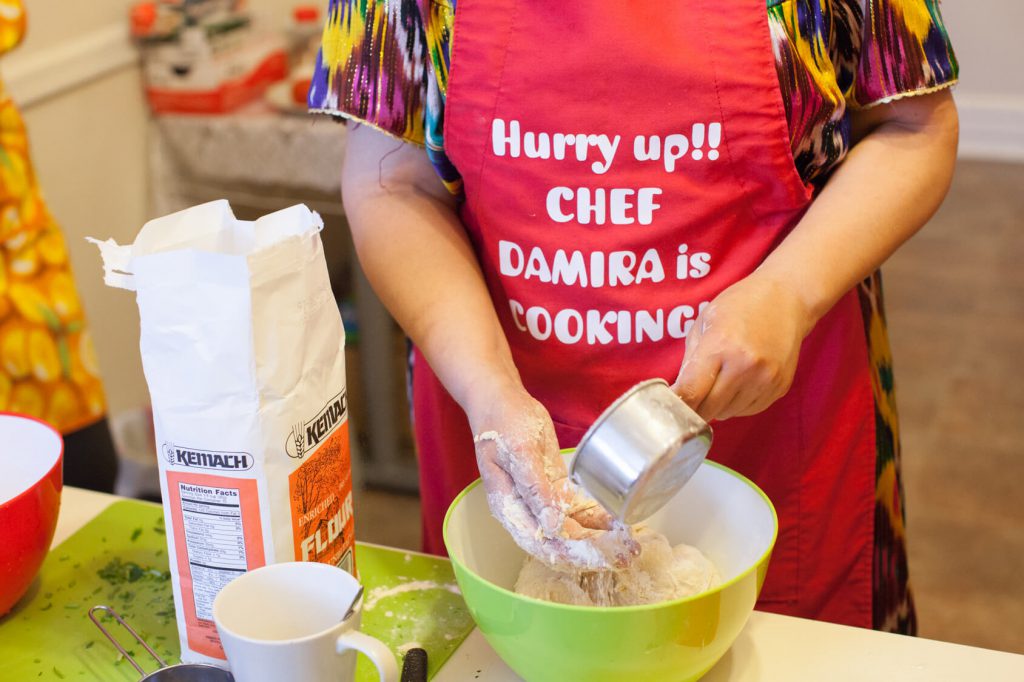

Once there, we tied back our hair and put on blue and red aprons (Damira’s said: “Hurry up!! Chef Damira is Cooking!”). On a white board in the kitchen, Damira had written out the cooking course for the day: Mashhurda (her husband’s family’s Mung Bean and Vegetable soup), Halvatar (Uzbek custard), Qovok Quymok (fried Gray Squash pancakes), pumpkin Hanum (a giant steamed dumpling), pumpkin sambusa (a smaller, baked savory dumpling pie) and a simple radish salad—refreshing and cold, finished with labneh—for a summer day.

Damira’s kitchen was clean and orderly, and her daughter-in-law Saodat was on hand to help, aiding with dish cleaning and preparation. We began with the mung bean soup. On the table, she gave us each cutting boards and knives. We all began timidly, in the presence of a master. “Who wants to start peeling and cutting carrots?” Damira asked. Slowly, we volunteered. With each ingredient, though they were not unfamiliar, we watched Damira handle and prepare them quickly and efficiently before we jumped in.

What a lot of us began talking about was how the toughest part of cooking a large meal was figuring out its order of operations: when to cut the carrots and put them in the pot, and when to start grating the squash for the pancakes, and how long to let the first ingredients for the soup boil down before adding more. But Damira moved around her kitchen attending to all these steps with easy confidence: It was multi-tiered obstacle course, mapped out in detail, and programed into her unconsciousness over decades.

At the stove, Damira told us an Uzbek lore about the custard, made of three simple ingredients: flour, oil, and sugar (and, in this case, with plenty of cinnamon—her personal favorite). Once, there was an Uzbek cook who talked about how difficult it is to make halva, despite the fact that it only requires three ingredients.

“One day, I decided I want to make halva but, when I have flour, I have no sugar,” Damira began recounting the tale, “When I have sugar, I have no oil; and when I have oil, I have no flour.'” And then somebody responds, “Ok, but why can’t you do it when everything is in your home?” As she talks Damira assiduously stirs the flour, sugar and oil, and it slowly turns into a creamy light brown sauce. The man answers the final question: “Because when I have it all at home, I am not home myself.”

We all react with a slow light laugh—stories like these are unfamiliar to us. But actually, Damira, adds, there is only one thing needed for a successful Uzbek custard: “Like a beautiful woman, every time, halva likes a lot of attention.”

She turned off the flame: It was perfectly cooked. She placed dollops of the sweet tan custard onto small round plates to set. Soon, it would be in our bellies, lopped up with thick, traditional Uzbek naan.

Before making the final three dishes, we took a break to eat. Already, we’d been at work in the kitchen for more than an hour. Personally, my feet were tired and I’d gone back in the dining room on more than one occasion to drink some cold tap water, which Damira and her daughter-in-law had set up neatly in water jugs. Sitting down for this midday repast—slurping the fortifying soup, finished perfectly with that tangy labneh, the same recipe that had been enjoyed by her husband’s family for decades—was very welcome. It was satisfying on a level—accompanied, as it was, with stories and detailed instruction—that I rarely, or rarely have, experienced.

The second half of the day we tackled the dumplings and radish salad. At this point, we’d gotten comfortable working and talking together, and developed an easy kitchen rapport. The initial timidity was gone and we all stepped in willingly as Damira gave us commands—how to roll out the dough, an easy way to grate a tomato into sauce, the most efficient way to break open an egg. Each instruction made the finished product cleaner, and faster. That said, while all League of Kitchens workshops come with printed packets that contain every recipe, a list of ingredients, and even local places where you can shop for them, Damira did not consult a recipe a single time. She eye-balled all ingredients. In particular, she’d add salt liberally, and at will.

In Uzbek cooking, she told us, it is said that when you add salt to a recipe, it means you love the people you’re cooking for. But now her kids tell her: Mom, it’s ok—we know you love us; you don’t need to add more salt. She tells us this with a smile, adding more salt anyway to a bowl containing egg and flour, that will soon turn into the dumpling dough.

Finally, it is time to eat the fruits of our labor. The food is phenomenal. Listening to the traditional Uzbek music, watching Damira take in all that we have just done, looking satisfied in her ikat, and eating the steamed dumpling filled with pumpkin and plenty of fresh cumin crush in all of our hands, we may have been in Borough Park but, really, all of us had just taken a full-sensory journey, far away.

As we finished, I decided to ask Damira how she and her husband had met. “It is just a normal story,” Damira explained, readily. “One day we were at a party at the State University in Samarkand,” she explained. “He came with his friends and I came with my friends, and we just looked at each other, and it was like”—she makes a motion like an explosion with her hands—”and then he invited me to dance and we danced together.”

She started to explain more about what it felt like, but asked Saodat to help translate. “You said it very well,” said Saodat. “Everything sparkled, she saw everything in his eyes, kindness, love, excitement, passion, everything, all at once.” Damira jumped back in. “And I said to myself: wow.”

These days, with all our devices, Damira tells us, we are too busy and distracted to notice thing like this—like kindness, and excitement and happiness—in someone else’s eyes. We certainly can’t see these things on a guy’s Tinder profile. We are all blown away, sad and happy at once to have heard Damira’s story of magic and eternity, her “normal” love story, and to know that today this scene is not the same. Yes, we were there to cook with her but, in the end, this whole endeavor was one of love. “Now my PhD is my three children,” Damira finished, “and I am happy to do it.”

Earlier, while we were preparing the fresh dill salad, we stood around as Damira eye-balled the ingredients—but she paused for a moment before throwing in a little more salt.

“More salt?” she wondered, asking us to test the composition of dill and oregano and radish, all resting happy in a pool of labneh.

“We already know you love us, Damira,” we told her.

“Ok,” she said with a hidden smile. “I don’t put more salt.”

All photos by Sasha Turrentine

You might also like