Talking to Benjamin Dickinson About His Williamsburg Creative-Class Satire Creative Control

Benjamin Dickinson (center) in Creative Control. Courtesy of Ghost Robot.

In Creative Control, set in near-future Williamsburg, director and cowriter Benjamin Dickinson plays David, who works at the marketing firm Homunculus. He’s tasked with leading the campaign for Augmenta, a virtual-reality system in the form of a pair of clear-framed hipster glasses (as we used to call them in the 2000s); to promote Augmenta, Homunculus has hired a “genius-level creative,” in the form of Reggie Watts (as himself) to produce some content with them. Meanwhile, David—stressed from work and the input of many screens, fighting with his hippie-inclined yoga-instructor girlfriend, and self-medicating with an ever-increasing pill regimen—begins, with Augmenta’s help, to lose track of the line between fantasy and reality. Gavin McInnes, the ousted cofounder of Vice, plays David’s boss at the firm, in a nod to the film’s very current, very local concerns: the essential interchangeability of not just reality and fantasy but art and advertising, innovation and commerce.

Creative Control opened in local theaters on March 11 and will expand to additional screens, including the Nitehawk, on March 18. Benjamin Dickinson answered a few questions of mine over email.

As this is a local magazine, and I’m told you live in Clinton Hill, I’m obligated to ask you how long you’ve been there, what you like about it, what you like about it, etc.

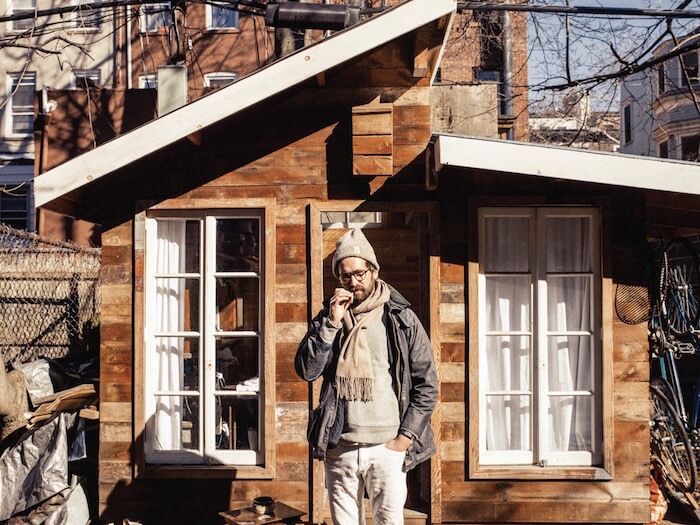

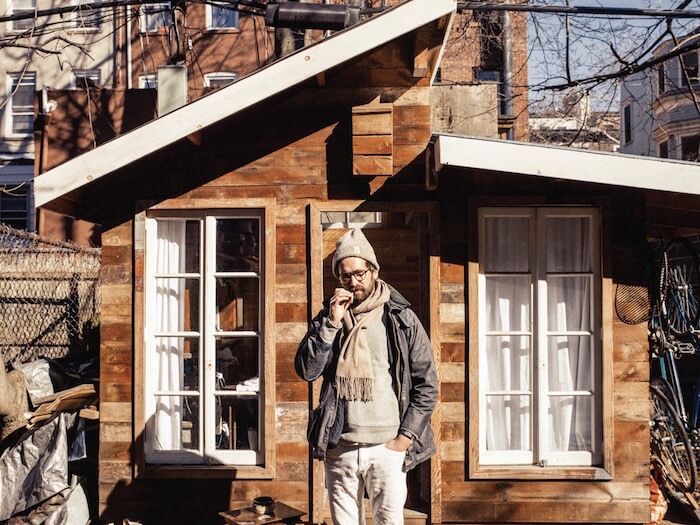

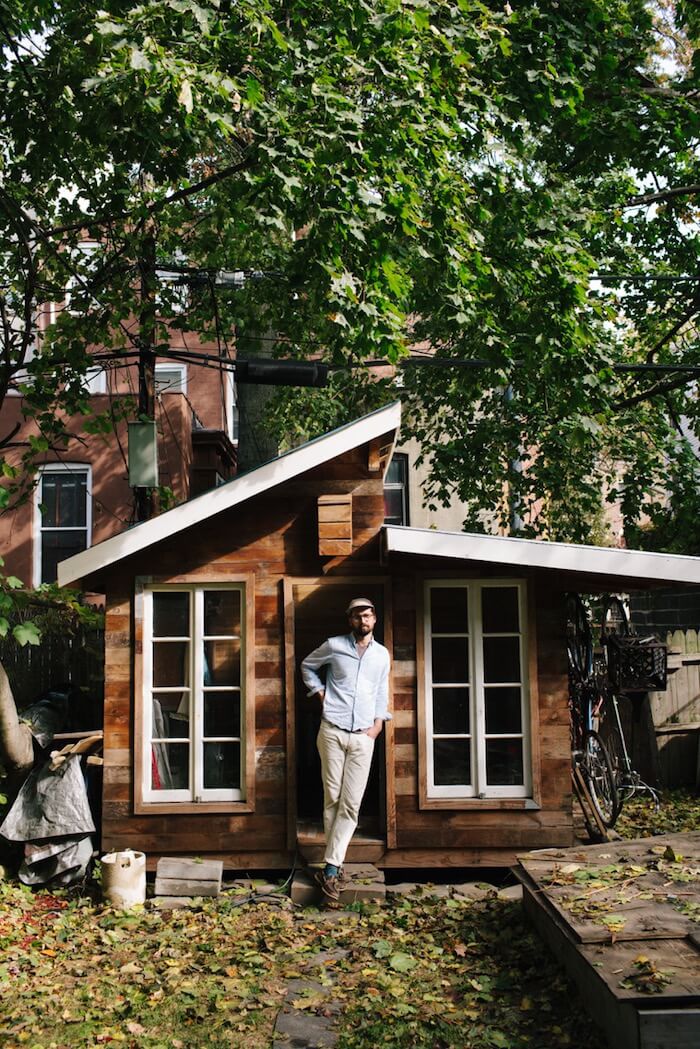

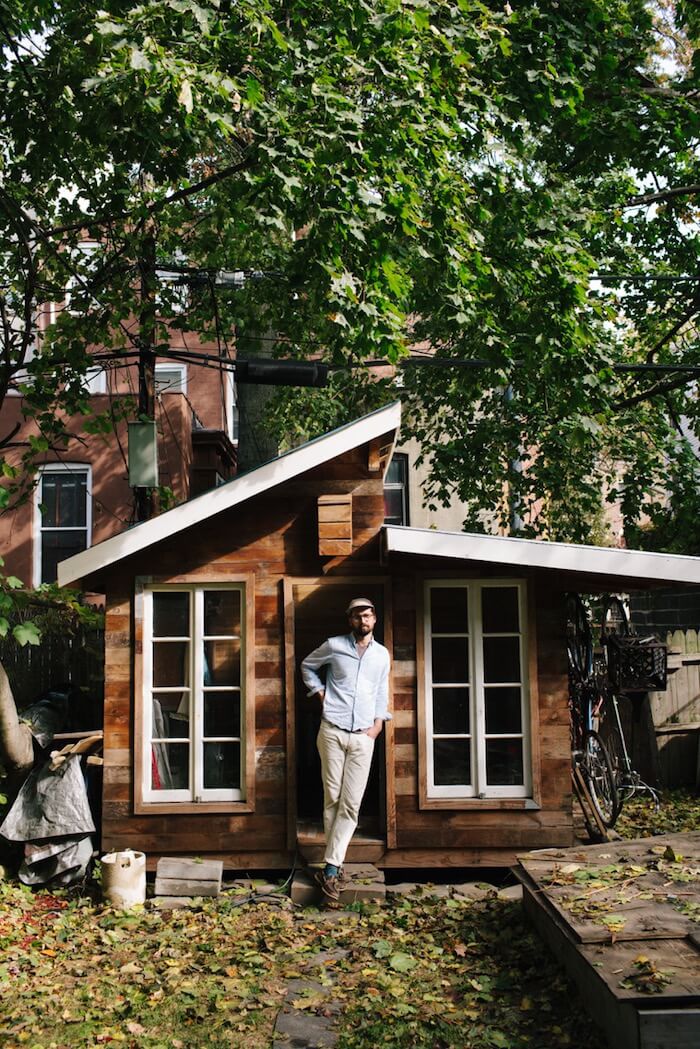

I’ve lived in Clinton Hill for five years; I like the old buildings and the big trees. It feels like a neighborhood, like I know my neighbors and the local shopkeepers, some of the local derelicts. Some of the people have lived in my building for decades. Betty King, my upstairs neighbor, tells me amazing stories about the 60s & 70s. Most importantly, I have a backyard. I built a shed back there with Adam Newport-Berra (Director of Photography of Creative Control) and Andrew Hasse & Megan Brooks (its editors). It’s where I write. Some summers I grow vegetables, depending on how much I’m traveling. I’ll include a photo.

In the near-future in which the film is set, the rise of North Brooklyn has culminated in it being basically the world headquarters for businesses like the film’s Homunculus, media companies connecting startup capital with cultural capital. I know that since graduating NYU in 2004, you’ve done some videos for DFA bands, and ads for companies like Ford and Puma. To what extent is the film derived from your personal experiences in the Williamsburg media-and-cultural industry—and how exaggerated do you feel the film is?

I’m reminded of a quote from Dawn Powell’s diary, “Satire is the technical word for writing of people as they are.” When Micah Bloomberg and I were writing this, we agreed that if we wrote about advertising & tech culture exactly as it is, without exaggerating at all, it would SEEM so ridiculous it would be as if we had exaggerated, or completely made it up.

But the second part of that quote is: ‘”Romantic,’ the other extreme of people as they are to themselves—but both of these are the truth.”

So it really depends how you slice it. I wanted to make satire and not a romance, because I was full of sorrow, because I was angry and frustrated. So yeah, from a critical point of view, I am accurately representing the milieu of the Creative Class of North Brooklyn, which, as you say, has been my milieu for a decade, although I don’t live there. And since it takes place in the near future, I’ve also extrapolated, to a certain extent, where it is going.

I want to focus a bit more on the title—it’s a phrase David uses in the context of his own work, though in another interview I read, you referred to “The idea [that] you can play an artist by working in advertising[.]” There’s also lip service paid throughout to the idea of the “creative” (a noun), a sort of black box that produces authenticity through some kind of mysterious alchemical product, and presumably legitimizes the whole enterprise. Is this an angry film, do you feel? Do you find this sort of compromise between art and commerce to be inevitable and/or in line with historical traditions of patronage, or fundamentally poisonous, or what?

Is the film angry? Yes. How feasible are the alternatives? Not very. Except perhaps to excavate some of this hypocrisy, look at it, and have a deeper understanding of ourselves and the world around us? And to laugh at it.

I am not a politician and I don’t expect this film to answer any questions or provide a solution. Rather to ask some questions about where our society is going with the current confluences of technology, drugs, and political economy. We need to discuss it.

Perhaps a related question: When Zach Wigon interviewed you for The L in 2012, about your previous film First Winter, you talked about how, “In a yoga community, even though you’re removing yourself from the madness of the technological world, the same problems are all there.” And Creative Control, with its opposite poles of high-tech urban capitalism and upstate yoga retreats, is very much a continuation of that idea, though with the emphasis shifted. Do you think of the two films as being in dialogue with one another? Is it a dialogue you want to continue?

Yes, initially I thought of Creative Control as sort of a prequel to First Winter. That if we had followed Juliette’s character after the end of Creative Control, we might have found her at the yoga retreat, during the apocalypse.

Hopefully we won’t be facing anything of that magnitude. I think I have become more optimistic recently. Spending a lot of time with Reggie has been a big part of that. He has a very cautiously optimistic vision of the potential of technology to help us all wake up.

Inevitably, my films will continue to be a dialogue between the spiritual and the material, the economic and the artistic, between the organic and the mechanical, because that’s where my interests lie.

Benjamin Dickinson in his backyard in Clinton Hill. Courtesy of Noah Kalina.

Antonioni’s come up in a lot of the interviews I’ve read with you about this film, in terms of the black and white widescreen look and the subject of personal alienation as a mirror of social alienation, though obviously the tone of your film is very different. A major thread of Creative Control is David’s descent into addiction, particularly to pills, and the toll that takes on his relationship—were there any influences you looked at or were thinking of particularly for the relationship drama in the film?

For the relationship stuff, I think I was really just reflecting some of the issues in my parent’s marriage, stuff I absorbed as a kid. Sounds weird, but honestly I can’t fight like David & Juliette fight in the movie. I am far too conflict averse. I have those fights in my head though. Writing those scenes was just writing down the fights in my own mind.

In terms of the addiction narrative, I’m sure I must have been influenced by Aronofsky’s Requiem for a Dream. That was so clever, how he did those drug montages. Because addiction is about repetition, the ritual of it, and the comfort of that ritual.

I’m really curious about Creative Control‘s costumes and hair. Everyone’s working a variety of on-trend looks with about 10% extra money and polish behind them, like the people at a rooftop dance party in a Bud Light Lime ad. What sort of discussions did you have about the styles in the film, what did you look at for inspiration, and where’d you source the clothes?

Ah! Exactly! We were very conscious of having the whole film use the language of a luxury advertisement. The idea that these people would appear to be living in an advertisement, but unlike in an advertisement, they would be unhappy and frustrated and anxious.

My dear friend Gina Aglietti did the costumes, and her background is in high fashion. She understood what I was trying to do. But I can’t keep all of the designers straight, we’d have to ask her where all the clothing came from.

There’s a lot of near-future tech in the movie, and an ambitious amount of VFX for a movie of this scale. How was the collaboration with the technicians and designers you worked with? Did you have a very clear sense of how the AR interfaces etc. would look and work, or were you more hands-off?

There were several phases to conceptualizing AUGMENTA. The first was thinking about the hardware, and how the physical object would function. I did most of that brainstorming work with Jake Lodwick, who also appears in the film as Gabe, the founder of Augmenta. I wrote a users manual as if AUGMENTA was a real product. We talked a lot about how you would control it, how flexible and programmable it would be.

The next phase was thinking about the design of the UI, which I worked on with Ethan Keller. Ethan had done some great concept videos for Microsoft. It was with Ethan that we decided on building the entire UI around a hexagon. We also did some branding work since that had to be done beforehand so the production designer could work it into the sets.

Finally, once we had an locked edit, we started collaborating with Mathematic in Paris. The lead designer was an amazing man named François-Côme du Boistesselin. The cut that he was using had a lot of temp effects to give him narrative cues, but in terms of how the UI would animate, how it would move, that was all to be determined. It took awhile to find the right feel. I knew I wanted it to feel very very light, and translucent. One day Francois showed me a very simple animation he did of a hexagon spinning around, which formed a cube. A hexagon is a cube drawn in 2D, if that makes sense. Anyway, that was the Ah-Ha! moment. From that point on, we did most of the work just discussing over three-hour dinners.

Had you given much thought to the possibilities of virtual reality technology before embarking on Creative Control? Are you excited about the prospect of working in VR in the future, or is feature-length narrative cinema forever the medium for you?

No, this film was the beginning of my interest in it. At least since the mid-90s, when it almost happened and then didn’t.

I had a great time making the VR piece—Waves—with Reggie, and we’re going to do more. It’s just fun to play with a new medium. Makes me feel like a kid again. But feature-length narrative is still my favorite medium.

Courtesy of Adam Hoff

You might also like