Nice Fish Brings Ice Fishing and Existential Reflection To DUMBO

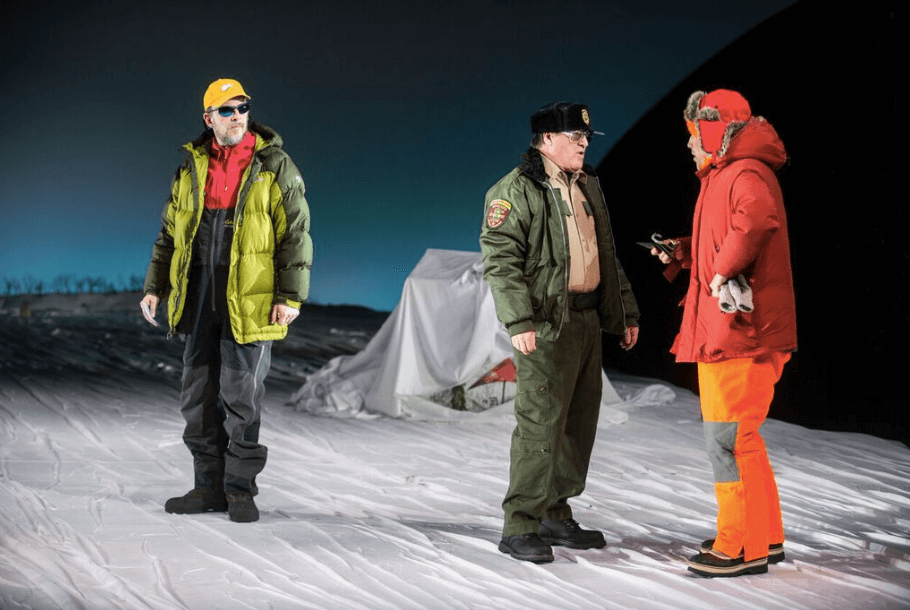

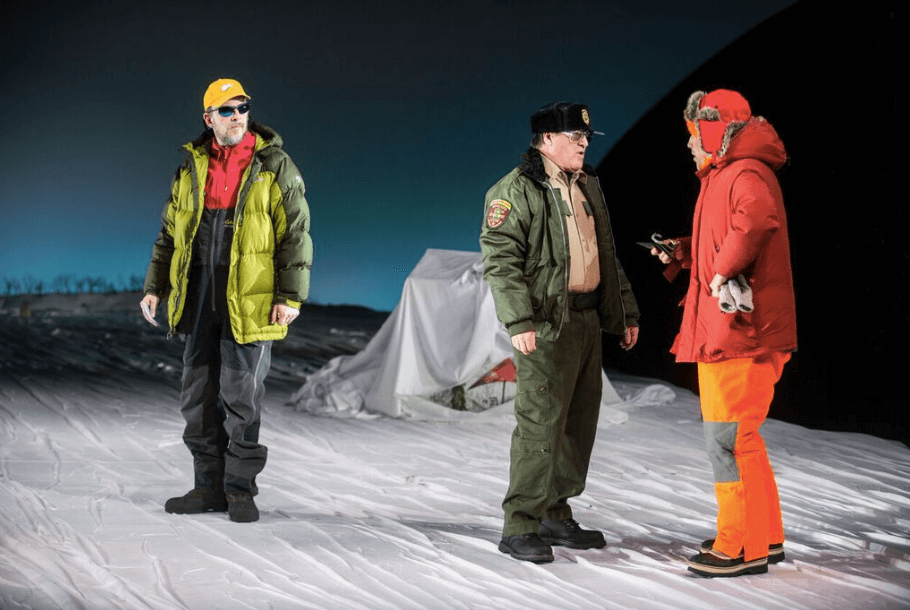

Jim Lichtscheidl and Mark Rylance in “Nice Fish.” (All photos by Teddy Wolff)

In Minnesota, ice fishing—waiting in the cold on a frozen lake or river, for hours, inside a miniature house, next to a deep, dark icy hole, in the hopes of catching a fish, which may never come—is seen as sport.

And now, a theatrical production that is based around it, “Nice Fish” (which first debuted at Minneapolis’s Guthrie Theater in 2013), has come to St. Ann’s in DUMBO for a month-long run.

You might ask yourself: But what happens in a play about sitting in below-freezing temperatures for hours on end? It’s a fine question. Because the answer is not one that highlights the action of the sport so much as the mindset required to do it, the character of a people who have made this seemingly painful activity a cherished pastime.

Nice Fish was created by an enigmatic powerhouse of a man, Mark Rylance—a Tony Award winning, Shakespearean English actor, who happens to have spent formative years in the icy stillness of Wisconsin. Rather than standard dialog, his script is made of lines from revered and award-winning Minnesotan poet, Louis Jenkins. (In 2008, Rylance’s first Tony acceptance speech was not a simple, “Thanks to this person, and thanks to that,” it was just him reciting one of Jenkins’s poems, unbeknownst to Jenkins himself, and to the bewilderment of the crowd. Afterward, the men struck up a friendship, and Rylance convinced Jenkins to collaborate on a play based off his poetry.)

Louis Jenkins was born in Oklahoma but has lived near the frigid shores of Lake Superior in Duluth, Minnesota for decades. His poems have simple names taken from slow, northern life: “Sainthood,” “The Talk,” “Diner,” Fish Out of Water,” Insects.” Rylance liked that Jenkins’s lines had an off-handed, conversational quality–qualities that imbue the character of a person who, like an ice fisherman, spends a lot of time inside of oneself, just thinking. When the temperature outside is many degrees below zero, and not a lot happens there anyway, a mind darts from this to that, and tends to focus on extremes: either the minutia of daily life, or existence’s bigger meaning. Nice Fish, suffused with Jenkin’s poetry, delves into both. And the result (directed by Rylance’s wife, Clair van Kampen) is a funny and profound riot.

The staging at St. Ann’s, a beautiful and newly restored old tobacco warehouse, is ingenious: a frozen, barren, snow-covered lake is made to look giant through skilled design and tricks of there eye. It rests at a slight upward tilt (so that its far shore looks, with just a little effort, like it’s hundreds of yards away), and the ridges of an enormous, rippled sheet become wind-sculpted snow dunes. At the lake’s far end there is a row of miniature trees, and, occasionally, headlights from a lone car. Sometimes a train’s whistle reverberates quietly. Civilization is far away and muted. The frozen isolation that is conjured is effective.

A large portion of Nice Fish is Ron (played by Rylance) and Erik (Jim Lichtscheidl), pals sitting side by side, making random observations about the big and small. Though spoken ostensibly to each other, each could be a thought normally kept within the silent confines of the brain. And the men react to each one–namely, they don’t often react at all–as if nothing had been said. At the outset, their thoughts are quotidian and very funny, and then become increasingly existential and philosophical.

For example, from his upturned fish bucket perch, Erik says, “In the morning, after I dressed, I looked for my wristwatch on the nightstand and discovered it was missing… Perhaps my wife has, for years, been harboring some secret grudge and finally, unable to bear it any longer, took revenge by flushing my watch down the toilet… nothing, nothing was the way I though it was.” Or Ron, in his perfect Minnesotan dictions: “When you are in town, wearing some kind of uniform is helpful… a team jacket, and baseball cap, and carry a cell phone,” he says, “Otherwise it might appear that you have no idea what you are doing, that you are merely wandering the earth, no particular reason for being here, no particular place to go.”

Eventually, Ron and Erik are visited by an officer from Minnesota’s Department of Natural Resources (who speaks at least twice as quickly as any Minnesotan I’ve heard in the 17 years I lived there), trying to give Ron a citation for not having the proper fishing license; Flo, a young erudite woman, and her grandpa, a spear fisherman named Wayne, also appear from a sauna house, set up a hundred yards away. It is during these interactions when the larger narrative becomes: What, really, is life all about? On a barren lake, in the freezing cold, this is the question the human mind is driven to.

“You look for deeper meaning in things… You find special significance in certain places and days, the cottage by the lake, Christmas, a certain Chinese restaurant in Winnipeg, your birthday, and set them up like signposts marking the passage of your life,” the men say to each other.

By then, in a turn to the surreal, they have transformed into an elderly couple, drifting on an iceberg that has broken off from the rest of the lake (fret not, if you ever ice fish, this never actually happens!), and are lifted off stage from straps that have descended from above; they are exiting life, lamenting that looking back on the end of it resembles a movie they didn’t understand, and that didn’t seem to have a plot.

Ice fishing, yes, leads you to a barren place that doesn’t seem fun–but ultimately, it’s a place familiar to everyone. “There is only one empty wilderness to explore,” Erik says earlier in the play, standing in a green puffer jacket, snow pants, and a yellow ball cap, surrounded by almost nothing: “The vast empty spaces in your head.”

Nice Fish at St. Ann’s, 45 Water Street, DUMBO; performances run through March 27.

You might also like