A Man of Many Names: A Lazy Afternoon with Questlove

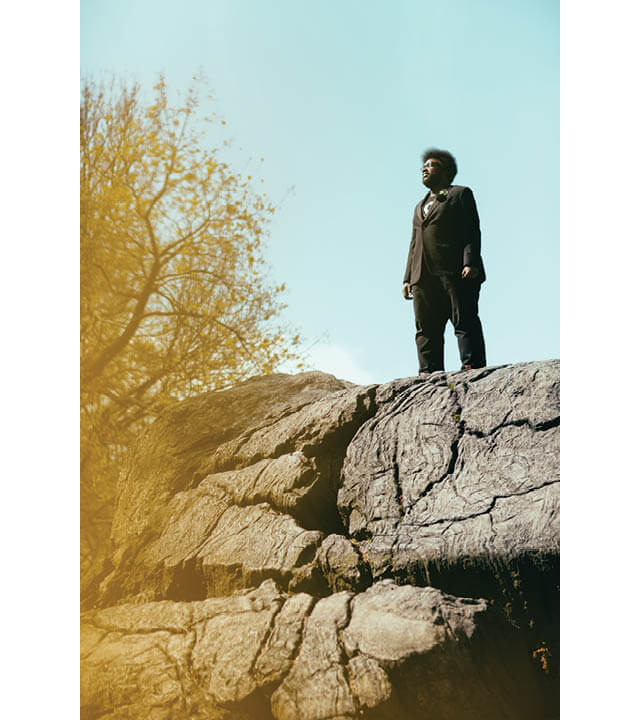

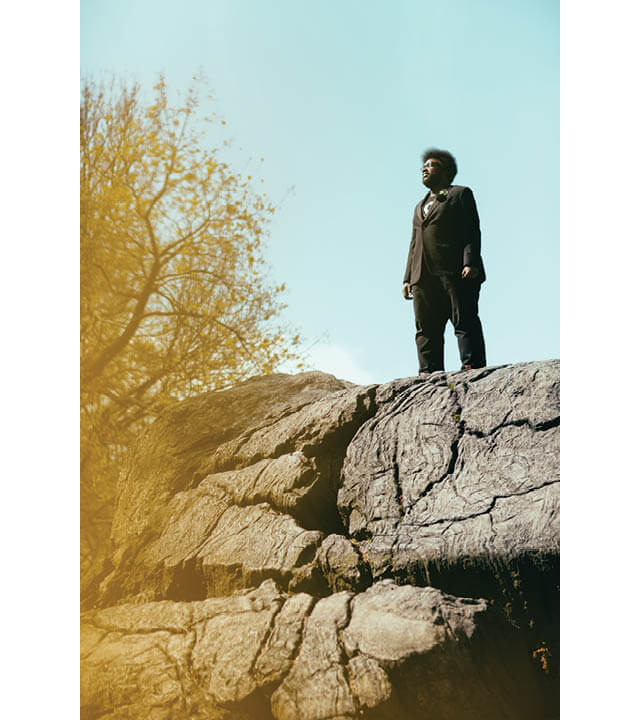

All photos by Eric Ryan Anderson

Running down Central Park West in the middle of the afternoon, I was having an absolute panic attack about being late to meet Questlove. Late enough, in fact, that I have to stop running to field calls from his publicist about where I am and how long it will take me to get there (“super close!” and “two minutes!” respectively). As I weave between strollers and dogwalkers on an absolutely gorgeous spring day, all I can think about is a 2012 New Yorker profile of Questlove that spent considerable time detailing how disrespectful and unprofessional he thought it was for people to keep each other waiting.

So I was pretty surprised to find him relaxed, happy, and generally unruffled when I finally collapsed next to him in a sweaty heap some 15 minutes later. The first thing I did was apologize.

He scoffs and leans over to me. “Aww man, that’s all smoke and mirrors,” he says. “I’m an artist. You ever know an artist who wasn’t late for everything?” I’m touched. Maybe it’s just a kind lie.

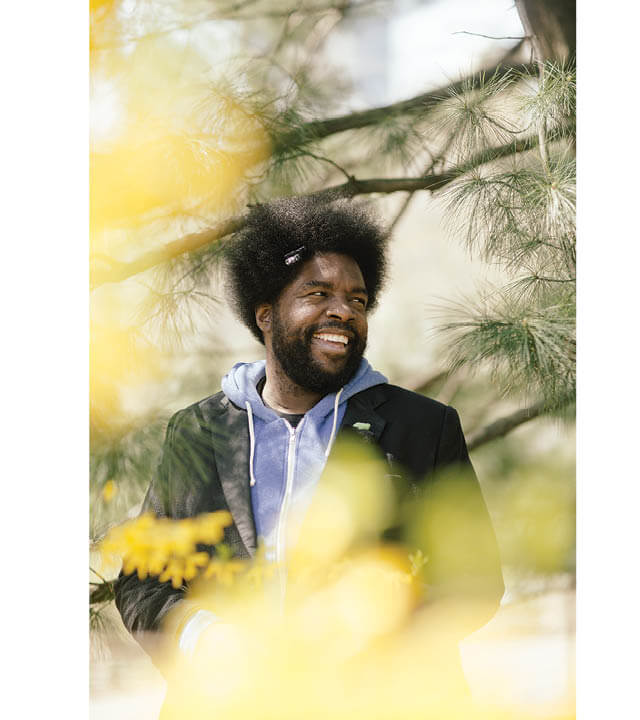

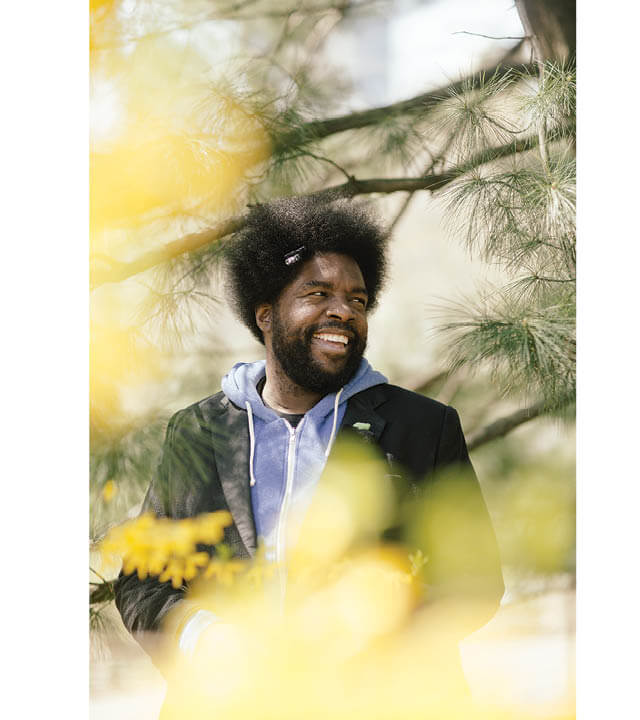

But honestly, he doesn’t seem to be seething. During the course of our afternoon, Questlove is kind, generous, funny, and engaged. On the whole, he seems pretty happy with how things are going.

Ahmir Thompson, more often known as Questlove, is a television star, food-world aspirant, actor, film composer, and, among other things, widely lauded drummer of The Roots. As we sat and talked, flower petals floated down from the trees and lodged themselves in the nearby bushes and his hair. People leaned out of their cars to yell his name and wave. He would smile and wave back.

It’s no wonder he gets recognized. Over six feet tall, with hair towering far above that, he has a wide, friendly grin; his lapel almost always features some kind of heart pin (he had a LEGO one for a while that I really liked), and a physical stature that reflects his lifelong love affair with food (in a 2013 Village Voice article, he credited Timothy Ferriss’ 4-Hour Body diet with dropping his weight from 440 to 350 pounds). Beyond physicality, there’s familiarity. Since 2009, The Roots have appeared on television as Jimmy Fallon’s house band, first on Late Night and later on The Tonight Show. Since Fallon took over that latter program from Jay Leno, in 2014, Questlove has appeared to nearly 4 million people every single weeknight.

He’s actually got some pretty good advice for anyone currently laying plans for their own future recognition. If you’re going to make up a name for yourself, he says, “Always give yourself soft consonants, or start your name with a vowel.” Generally, he said, you want to pick a name that doesn’t startle you when strangers yell it to your face. “I hang in places people don’t expect me to be, and they’re not sure it’s me. So, the only way for them to find out is to wait 0.3 seconds, until right when I pass them and yell, ‘QUESTLOVE!’” he says, affecting an usually deep masculine growl.

Around this time, the coterie of professionals who keep his schedule begin herding him into a large black SUV that’s waiting to whisk him to his day job as musical director of The Tonight Show. I’m told that, given how late I was, I should feel free to ride in the car with him to NBC studios at 30 Rock. I settle myself into the middle seat next to Questlove, and we’re still talking about his name. Specifically, its evolution from ? to BROther ?uestion to a few other permutations before settling where it is now. I lay my digital recorder on the seat between us, but he picks it up and begins speaking into it, like a very practiced interview subject.

“Well, here’s the thing: I hate monikers. So I wanted a question mark symbol,” he says. “The thing was, journalists kept calling me Mark. I was like huh? Yeah, you know question mark. So it evolved into the worst acronym ever, BROther ?uestion, which is why people would be like, ‘Brother’? No, it’s an acronym… so that didn’t work.”

Such are the perils of picking your professional identity as a teenager. Questlove and his Roots bandmate, Black Thought (Tariq Luqmaan Trotter), started the band as high school classmates in Philadelphia and have been at it together (with much rotation of personnel in the band around them) ever since. Their work stood apart from other artists of the time for its mix of jazz, soul, and hip hop, as well as its willingness to be extremely odd. One song, “Lazy Afternoon,” from 1993’s Do You Want More?!!!??!, is one relatively short verse repeated over and over like a jazz earworm, for just over five minutes.

It was with 1999’s Things Fall Apart that the band achieved major national and international recognition. With complex lyrics, a leitmotif of loss and disillusionment, and guest spots from artists like Common, Mos Def, Jill Scott, Eve, and Erykah Badu, it was a smash hit, eventually certified platinum and winning a Grammy.

Unlike many (or virtually all) hip hop artists, the band was, in fact, a band—while they used samples, the core of the Roots’ music was live instrumentation.They were famous for their long sets and wild improvisation. Roots shows were talked about in the mid 00s the way people had talked about Bruce Springsteen concerts a generation earlier: hours-long endurance tests for the audience and band alike. This gave the band a certain entrée into otherwise mostly white (or at least mostly non-hip hop) music festivals and packaged tours that other hip hop acts of the time did not have. The band has twice played Bonaroo, spent 2007 touring with The Dave Matthews Band, and are frequent guests at Brooklyn Bowl (club owner Peter Shapiro’s seal of approval is a jam world bona fide if there ever was one).

By 2008, Questlove says, the band had finally reached “the financial mountaintop,” meaning that it was comfortably profitable to bring the band, support staff, and heavy equipment on tour. The only problem? They weren’t sure they wanted to do it any more.

“Bands don’t last after ten years,” he says. By this point, The Roots were in their 20th. The band had long since become where its members worked and how they made a career, not an adventure they were sharing. “Like, we started in high school,” he says. “We’d spend nights at each other’s houses, best friends… and then, you know, OK, this guy got a girlfriend. This guy’s getting married.” In short, they were drifting apart.

Plus, it was beginning to feel irresponsible to be touring as much as much as they were. “It’s one thing when your babies are not of age and you do five weeks in Australia,” Questlove says. “But it’s a whole ‘nother thing when they’re 8 and you’re not making baseball practice.”

They found themselves wishing for “a Celine Dion situation,” a long-running, stable gig at a casino. In 2006, Questlove revealed, they seriously considered signing a long-term deal to appear at The Borgata, in Atlantic City. “However, I personally just felt like the Wikipedia page in my mind didn’t want to end there,” he says.

It was around this time that the band met the man who would totally change their lives: Jimmy Fallon. At the time, Fallon wasn’t up to much, his movie career basically in terminal shape after bombs like Taxi. He was keeping busy doing cartoon voices, starring in great low-budget movies like Drew Barrymore’s rollerderby dramedy Whip It!, and terrible low-budget movies like The Year of Getting To Know Us, in which he appeared alongside Tom Arnold.

Questlove was taken with Fallon when they met in Los Angeles, and invited him to come see The Roots play UCLA’s Spring Fling. “I only invited him—I knew he was going to say no, but I only invited him because I’d look real cool having 2008-era Jimmy Fallon coming to the show. Hey, my cool-ass pal Jimmy Fallon. You know, that guy. And he came by, and the weirdest thing happened,” Questlove says, before re-telling an origin story that is now well-practiced.

“I was doing an interview in a trailer,” at the UCLA concert. “And when I walked out the trailer, the eight of them—Fallon and the seven Roots—were making a human pyramid. He was able to disarm us in seconds. Usually people are conscious of it: Oh, the nerdy white guy and a bunch of black guys. They’re a little quiet or whatever. Like, he was silly and was just proud of it. And was so silly that it made us silly. Like, we rock $500 sneakers. I’m not getting my knees dirty on the grass at UCLA to do a human pyramid! Like, imagine the Wu Tang Clan decided to play in a playground. That’s what it looked like. And I’m looking at my manager and we just stared there shaking our heads. I was just like, we’re stuck with this guy, aren’t we. And he just looked like, I’m afraid so. And that’s when I knew, I instantly knew. And what was even crazier was that every show after that show, it was as if that was the moment The Roots started. Whatever happened before, I don’t even count no more because suddenly we weren’t afraid to be—we weren’t guarded with each other anymore, for some silly reason. Suddenly, we became friends again.”

Just as our car pulls to 30 Rock, Questlove stops himself mid-sentence and leans across my lap to stare out the window at a bright red food truck, excitedly saying, “Oh my god, Valducci’s is on this block?! Have you ever ate that pizza? Dude, oh my god, Valducci’s is like the best pizza ever. Have you ever tried it?” It’s the most excited I will see him all day.

Honestly, it’s not my favorite, so I offer a weak, “Yeah, uh, there’s lots of good pizza?”

He looks directly at me and says, “I love Valducci’s” in a tone that makes it clear that it’s not up for debate. He promises to send an intern out for some slices, which I take to be just a conversation closer, a sort of, “let’s definitely get coffee some time.”

Anyway, I figure, I won’t be able to see what happens. I’m going to lose him at the door of 30 Rock. Rushing now for the second time today, I ask him one last question.

“Oh, sure,” he says. “We can talk about that upstairs.”

I’m not sure this was the plan all along and I misread an email, or if he’s just winging it, maybe, or if I’m just devastatingly charming, but in any event I do not ask any questions as we walk down the marble corridors of NBC studios on our way to its brass bank of elevators. But first, actually, there’s a little problem.

Questlove has developed a bad habit of forgetting his wallet at work when he leaves for the night. It’s the perfect drum mute, he explains to me, so he ends up leaving it on the drum set in his dressing room at The Tonight Show, which doubles as The Roots’ recording studio. When I point out to him that the show would likely purchase him an actual, purpose-built drum mute, he grunts dismissively and waves his hands. It’s as if I’ve told Willie Nelson he could buy a new guitar instead of playing the same old one over and over.

This habit has some consequences. Not only is it embarrassing when he takes his friends out to dinner and suddenly can’t pay (on a recent night, even though the restaurant offered to cover dinner, he made everyone wait while he ran back to the office to get it so he could pay, himself), but he doesn’t have his ID to get into the elevators when he arrives for work at the very security-conscious NBC offices. As he’s escorting me upstairs, he has a brief confrontation with the guard at the gate. They don’t want to let him in.

“Come on, it’s me!” he says, joking, but also a bit exasperated.

“I know it’s you,” the guard says. “But where’s your ID?”

A short time later, we’re upstairs. It’s like trailing the prom king: Everyone he passes knows him and says hi. He knows everyone’s name. We walk past bobbleheads of the band, sitting on a small shelf outside their dressing room, next to a Grammy award, also belonging to them. As soon as he reaches a reception desk, Questlove says hi to the young woman working sitting there. Then it’s down to business.

“Did you know there’s a Valducci’s here? Can you send an intern to get me some?” Then, turning to me, “Do you want any pizza?” For some reason I will never be able to explain, I pass on eating pizza with Questlove.

We wander into the Roots’ dressing room, actually two and a half rooms crammed full of drums, keyboards, and knick-knacks: a plastic flamingo, an Oscar the Grouch plush doll, framed records, Elvis Costello’s guest badge from a visit to the studio, a photo from a parody of Downton Abbey that features Fred Armisen in a dress and Questlove looking sharp in a tuxedo. Mob Wives is playing on a flat screen TV mounted to a wall in a smaller room, in the very back, with couches along the walls (Questlove’s drums are stuck in a closet, as well). We settle in to wait for food.

The late-night talk show jobs, have given Questlove the stability—psychologically, financially, temporally—he was looking for.

“Yeah, I have a day job,” he says. “What this enables me to do is to really pursue other dreams and goals and things that I normally couldn’t do otherwise.”

Chief among those goals? Food, something in which Questlove has a passionate, life-long interest. As a child, he says, “Thanksgiving didn’t mean anything to us, because every Sunday was Thanksgiving.” His family would gather around for a feast—ham, fried chicken, okra, greens, cornbread, yams, rice, potato salad—which his grandmother, his aunt Corinne, and his aunt Laura would somehow miraculously prepare while also spending most of the day in church.

“I went to the type of church that you had to be there at 7am,” he says, “and then there’s a break at 10 and then you go back at 11. Church is over at 4 and there’s like three sermons. You get home at 5. Yet dinner was always ready at 6:30.”

He broadened his culinary horizons in the late 1970s, while traveling with his father’s doo-wop revival band. “Now everything is mixed, but there was a point when America was really regionalized,” he says. “So, food in Miami was way different than food in Los Angeles. In Los Angeles, the idea of a pineapple on your pizza was just in Los Angeles.”

Questlove’s food obsession has taken multiple forms. He spent many years perfecting his fried chicken recipe, with the ultimate goal of opening a food truck, which he described with typical ambition and insight as “Mr. Softee for drumsticks.” To perfect his recipe, he’d gather friends in his apartment and give them chicken from around the city—Blue Ribbon, Marcus Samuelsson’s Red Rooster, EN Japanese Brasserie, and more—as well as his own special recipe, worked up in conjunction with his partners.

“We were always in last place,” he says, laughing. But he kept going, though, 17 or 18 focus groups taking place over several years. I tell him that other people as busy as him, or even those much less busy, might have just taken it as a sign that their food wasn’t very good and moved on.

“Nah, man. By that point I was determined,” he says. “We’ve been doing this shit for a year. I’m funding this shit. We better make it happen.”

And, eventually, it got better. Questlove’s friends came around, picking his as the best. He even felt confident enough to take part in a 2012 TV chicken battle with Momofuku’s David Chang. Admittedly, he lost (a panel of judges including John Slattery and Tina Fey unanimously voted for Chang), but it was a big step. Not long after, he launched a proper home for the chicken, Hybrid, a short-lived Chelsea Market stand in partnership with Philadelphia chef Stephen Starr.

Since 2014, Questlove’s food focus has been on events, like the upcoming Taste Talks series (put on by Brooklyn Magazine’s parent company, Northside Media), and his own series of salons in his New York City home, attracting chefs like Wylie Dufresne, April Bloomfield, Brooks Headley, and Craig Thornton, of Wolvesmouth, to work together in his small kitchen serving a select group of guests (these parties have also been filmed and put online, though Questlove is reluctant to call it a web series). Past guests have included Grimes, Bat for Lashes, Best Coast, Lykke Li, Adrian Grenier, Miranda July, and Sasha Grey.

At first, he admits, he was unsure how it was going to go “I was like, is this going to work? Are they going to collaborate?” he says. But he’s found himself impressed by the food world. “I thought it was going to be petty, and it’s so not petty,” he admits. This was especially shocking given how prone restaurants are to fail, something he knows firsthand after Hybrid’s 2013 shuttering.

“To keep a restaurant thriving—to keep it open is one thing, but to keep it thriving and on the radar, especially when new blood comes in,” is extremely hard, he says. “The way that musicians think, it’s like, off with their heads.” But not so much in the culinary world. “And I’m shocked about that. I mean, just to have that community work together is awesome.” He wants to keep expanding the salons, if for no other reason than so that he can stop having awkward conversations with the people who don’t make it on to the very small guest list.

“There’s always that one person that’s just like, ‘Soooo, yeah. I heard you had a food salon?” he says, imitating his cordially devastated friends who get left out. “I don’t want it to be that way. In a perfect way, I would love to bring it back to my childhood where there’s this kind of a weekly occurrence.”

It’s around here that the intern comes back with the pizza. “Wow, did you run there?” Questlove asks the obviously confused young man. It had actually been almost an hour since he’d left. Questlove had been having such a good time, he hadn’t noticed. ♦

You might also like