Trials of a Century: On O.J.: Made in America

“If you’re a celebrity you have no color.” -Robin Greer, Friend of Nicole Brown Simpson

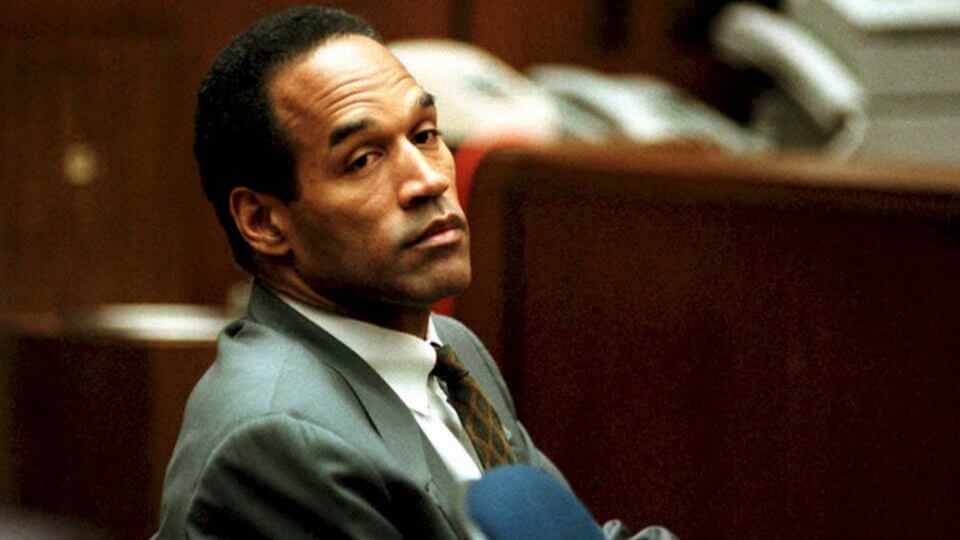

That June 1994 Time Magazine cover pissed us all the fuck off. When we realized it wasn’t a printing error, but a deliberate darkening of a medium-brown-skinned African-American, O.J. Simpson or not, we understood that the national conversation around the guilt or innocence of the former football player and celebrity would pivot towards race. Newsweek’s editorial team used the same mug shot for their cover in the same week. We looked at them side by side and those images became the filters through which we began to process a murder case much larger than the victims, the attorneys, and the accused.

That summer, between watching the LAPD collect evidence and build a case against Orenthal James Simpson, the football star, American hero and icon, for the double murder of his estranged wife Nicole Brown and her friend Ronald Goldman, the political debate was steeped in determining the feasibility of healthcare reform. That effort was led primarily by First Lady Hillary Rodham Clinton. That summer, I was in Milwaukee, back home from college, interning for Senator Russ Feingold, and subsidized my service by selling winter coats on weekends for JCPenney. I watched reruns of the first season of The X-Files at night and had a minimal interest in basketball. I logged constituent calls for the senator, drafted correspondence in response to each of those calls. Most of them, older Americans who seemed to have a singular source of news, repeated ad nauseam what they heard on morning news talk shows. The merits of the proposed legislation were completely erased. One day, I logged over 300 calls from angry, older Wisconsinites. Occasionally some wanted to debate. In 1994, there was no internet as we know it. I got to sit in on a meeting between the senator’s staff and members of the NAACP around a potential issue with racial discrimination and a local business.

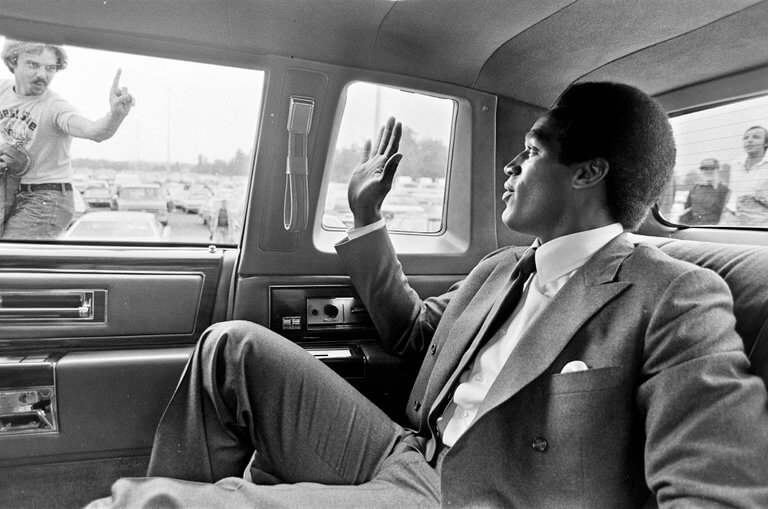

I didn’t have much of a language to articulate the anger I felt for the characterization of a football hero I never cared about. My knowledge of Simpson lived inside warm chuckles from my grandmother who really enjoyed the Naked Gun movies, or in passing commentary from my uncles over potato salad and ribs, who remembered maybe a play or two from “The Juice.” I may have remembered his face from a Wheaties box. I was too young to have any memory of the well-dressed black man running through the airport with a briefcase, barreling toward a Hertz counter to pick up the keys to his rental car. What I did know was that the choice Time Magazine editors made to deliberately darken a brown-skinned man in 1994 connected to a cultural legacy, a construction of anti-black hatred, and now the safest black man among white society had been reconstructed into a blackness white people feared. Is this how all white people see black men?

The memory of that anger flooded back with a bitter vengeance upon viewing ESPN’s seven and a half-hour documentary, O.J.: Made In America. The large canvas that filmmaker Ezra Edelman provides is as necessary as it is literary, a precise examination of our national attitudes about identity, racism, domestic violence, class and celebrity. Through concurrent stories, Edelman humanizes villain and victims, filling out an exhaustive picture of the invention of O.J.Simpson, a constructed self that conformed to expectations of white society while pointing to early signs of domestic abuse. Those twin plots become the lens through which we see how Simpson’s reinvented self revealed all our shitty selves and systems, culminating in the “Trial of the Century” and its outcome, an indictment and reprimand of our failure to resolve the problem of the color line.

***

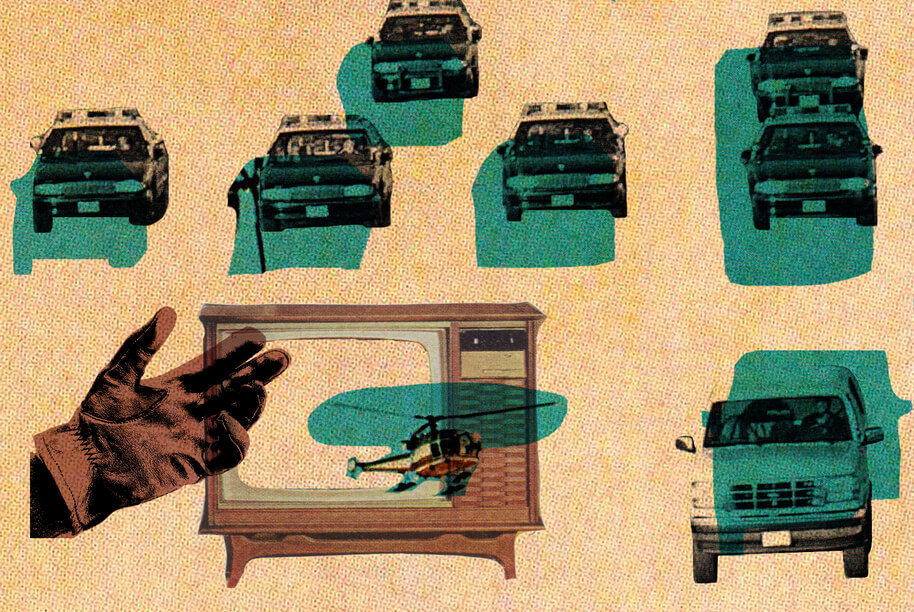

“If O.J. Simpson were black, that shit wouldn’t have happened. But since he transcended race, to the exalted status of celebrity. He got a motorcade.” – Zoey Tur, Brentwood Resident

The summer O.J. fled in that white Ford Bronco with his ace A.C. Cowlings, drove all over the freeway with a gun to his head and an LAPD escort on national television, I thought of Bigger Thomas, the protagonist of Richard Wright’s 1940 novel Native Son. Bigger Thomas is a thoroughly unlikeable character. He is flat, lacking any dimension, and in Richard Wright’s imagination, was the canvas on which he could arrange America’s class and race anxieties into an equally flat melodrama about what it meant to be black and American in the early twentieth century. Wright had the distinction of being one of the few black writers achieving mainstream literary fame in 1940, a distinction perpetuated into the reading list of canonical texts for my high school honors English class. And let me tell you something: I hated that fucking book. Fuck you Richard Wright, I may have mumbled to myself reading it or in class. When you’re one of the few black students in honors English at your predominantly black magnet school, the shittiest job you have been given is to explain the multitudes of black humanity and simultaneously make white people feel safe as they fumble in a haze to understand. That is the race card you are dealt.

Thomas accidentally kills (who the fuck accidentally kills?) the daughter of his white employer. At this point in the novel, the reader wonders if this is a bad modeling of Steinbeck’s Lenny, but we soldier on. Then, to cover up his crime, Thomas dismembers his victim’s body, and feeds her to the furnace of her own house. This is all very bad. Thomas flees to his black woman, who is also given short shrift (even sixteen-year-old me wasn’t sure Wright respected black women), until he kills her, too. Thomas spends a considerable amount of time on the lam from Chicago cops. The wild thing is that this utterly implausible, radicalized and misogynist nightmare of a book became a bestseller. Which means white Americans in that time readily consumed this high-concept, poorly developed horseshit long enough to confirm their biases towards black men and boys.

The year I read Native Son, an all-white jury from the Los Angeles suburb of Simi Valley acquitted four white LAPD cops for beating Rodney King on the side of an L.A. highway. There was videotape. If I was to understand the plight of black men in encounters with law enforcement in 1992, it was clear that to be a black man was to be stained with inherent criminality, and that it was reasonable in the eyes of white America, that the black body could be crushed—wrecked—and that my fellow citizens would only ask, “What did he do to deserve it?”

For most Americans, Los Angeles is synonymous with the glamour of Hollywood, photographs and films, a small frame that ignores daily realities for working-class communities of color. Moreover, to understand Los Angeles is to understand the relationship between highways and cops. For this, OJ: Made in America never feels overwrought in digging so far deep into the past, as much as it feels necessary in laying the foundation for Los Angeles of 1994 and 1995. From its outset, the actual Simpson murder trial was never simply about the brutal double murders of Nicole Brown and Ron Goldman. Frenzied media attention was less about the facts of the case than about, as writer Walter Mosely sharply notes in the documentary, “Black American Hero kills white woman.”

That distinction is crucial to unpacking the pathos of the American public, still suspicious of (and scandalized by) relationships between the races. We had entered the last decade of the twentieth century with a jaunty anthem celebrating unity along the color line and a twee video of symmetrical faces morphing into each other. Which is to say, even Michael Jackson was out here in these streets, concerned about social injustices while talking unity, confusing us with his struggles with his own blackness, whether by plastic surgery, or by providing us with that most exquisite black pride cultural document, “Remember The Time.” Meanwhile, five kids from Compton chronicled their frustrations over the long siege between their generation and law enforcement. Decades later, the current movement to end police violence in black communities would later declare their anthem prescient.

From the Watts riots of 1965 to the 1979 police killing of Eula Mae Love, a single mother whose tense interaction with cops ended in them shooting her eight times on the front porch of her home in front of her kids, the grievances of black Los Angeles were casually ignored. Love’s killing (The crime? Nonpayment of a $22 utility bill. The officers were never charged) was an acute affront and fueled outrage by activists and local politicians. “Once again we have a member of the black community, dead, under circumstances that are highly questionable at best,” said a young Maxine Waters, then a state senator, after Love’s death. LAPD’s then-police chief remained clinical in his response to community outrage, simply saying that he was “Deeply sorry that it happened. But It did happen.”

The repetition of these incidents are no news to black Americans. The strength of this documentary series is that it orders the chaos that we have already witnessed, making it plain for viewers who argue that the black anger to state violence perpetrated by police departments nationwide is overblown, that their beliefs, too, exist in a continuum of white indifference (and conscious ignorance) to black pain.

That simmering anger and frustration persisted in the black Los Angeles, and became more pointed in the aftermath of the 1991 criminal trial of Soon Du Ja, a Korean grocer who murdered fifteen-year-old Latasha Harlins. Soon, who shot Harlins in the back of the head after Harlins had turned to leave his store, was sentenced to five years of probation, 400 hours of community service, and a $500 fine. Devastating security camera footage of Harlins’ killing surfaced thirteen days after video of Rodney King’s beating emerged. These events were not tangential to Simpson’s trial and double murders of Brown and Goldman. Edelman makes clear that black communities in Los Angeles lived in an alternate universe. The big story of the 1992 riots is critical to understanding how hypersegration and racially systemic bias within the criminal justice system would shape the composition of the Simpson jury, and finally, how impossible it would be for racial politics to not enter the courtroom.

***

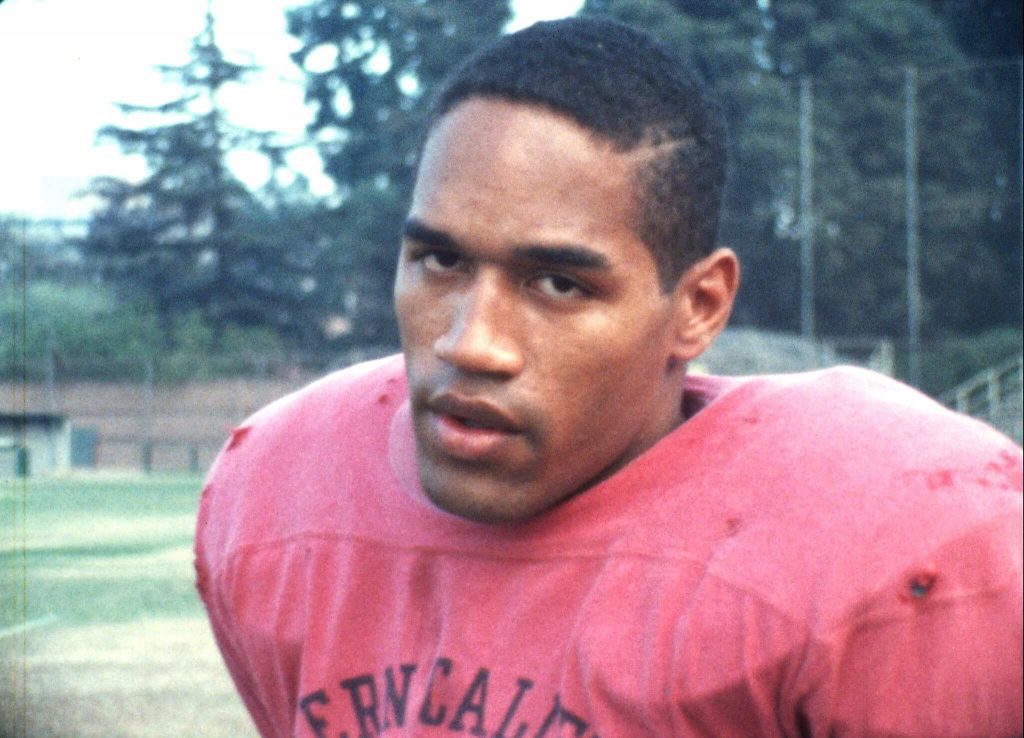

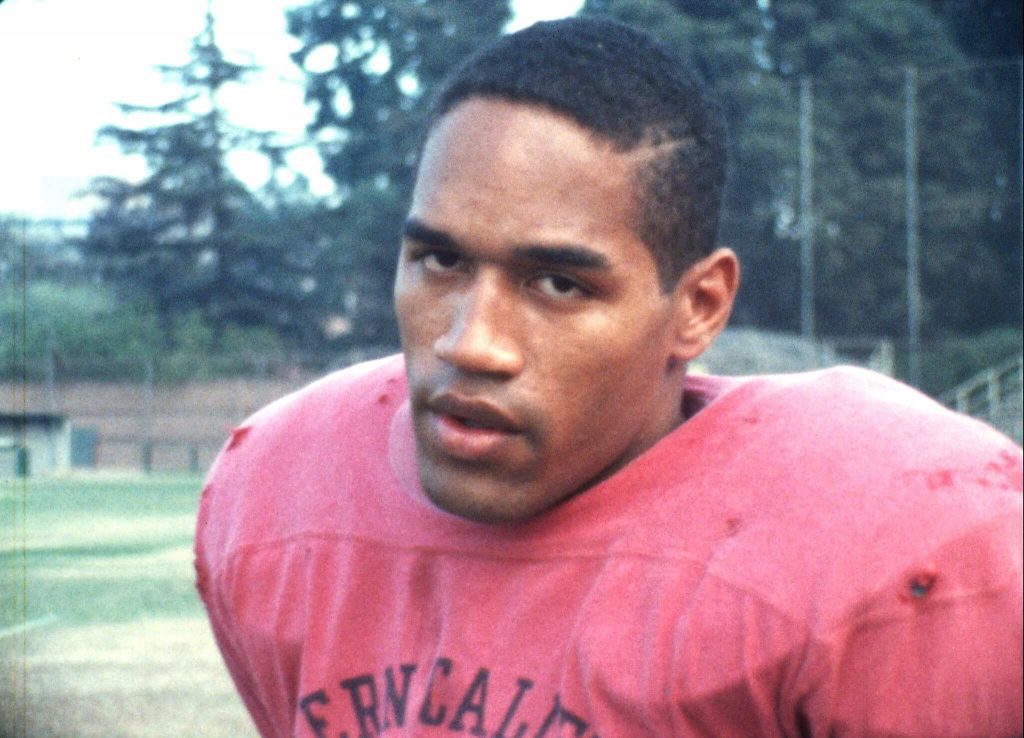

“Where did he begin to write this novel about OJ Simpson?” – Robert Lipsyte, Sports Journalist

Here we consider the impact of Coalhouse Walker, Jr., the hero in E.L. Doctorow’s bestselling and award-winning novel Ragtime. Doctorow’s time-bending epic attempted to excavate the origins of America’s consciousness, reconciling tremendous economic and social change as well as white anxieties around class, ethnicity and race. Ragtime’s themes resonate as a counterpoint to Simpson, the self-invented man whose individual actions led to his downfall. Simpson’s overlooked quest to parlay “sports celebrity” and “advertising icon” into “venerated actor” is illuminating. As Hollywood prepared to adapt the novel, Coalhouse Walker was a role that Simpson vigorously sought. It is an excellent, yet overlooked detail in the Simpson narrative that Edelman skillfully interweaves into Part 2 of Made in America.

“When I read the book, I could identify with this guy so much—it was a black guy at a time where you’re supposed to know you’re ‘black,’ supposed to know you had a place,” O.J. says in an archival interview.

“It occurred to Father one day that Coalhouse Walker Jr. didn’t know he was a Negro,” the novel’s unnamed narrator observes. “The more he thought about this the more true it seemed. Walker didn’t act or talk like a colored man. He seemed to be able to transform the customary deferences practiced by his race so that they reflected to his own dignity rather than the recipient’s.” The comparison between Walker and Simpson is really compelling, and I wondered briefly what degree of hubris Simpson possessed to ever believe he could bring the emotional complexity of Coalhouse Walker to life on screen, given his struggle to deliver a real performance in film-that-time-forgot Capricorn One. Coalhouse Walker Jr., in Doctorow’s imagination, was a self-fashioned black man who didn’t necessarily deny his blackness, as much as he refused to be confined by white men’s definition of blackness.

Perhaps I am misreading this character.

“He suffered for his pride, which makes him the right soul for Coalhouse Walker,” says Simpson’s friend and Capricorn One director Peter Hyams. Maybe Hyams is right, but this read is telling. There’s a naïveté in assuming that Walker’s pride was his undoing, and not the fact of racism. Walker’s principle crime was asserting his personhood and citizenship while social norms of his day allowed white men to remain blameless. “I think I created an image by being me. My life is mine. I’m not prejudiced in any form,” O.J. says in the same clip. There’s another pretty Tony McSchmaltzy clip, where an interviewer presses him on his controversial role in made-for-TV film A Killing Affair, in which his character is romantically involved with a woman played by Bewitched star Elizabeth Montgomery. O.J. in this movie and interview had to confront racism, a move he’d sooner avoid offscreen. (It was good TV in 1980s America to invoke the taboo of love across the color line.) Simpson wanted the role to challenge himself. “I felt I was today’s Coalhouse Walker,” he said.

Sports journalist Robert Lipsyte’s early impressions of O.J. Simpson really key into the notion that Simpson was always self-aware in constructing a character that would be pleasing to white people, his way of fulfilling whatever private ambitions he had. “Think of O.J. as an American man, a poor American man, a tough American man who’s recreating himself in ways that people would accept and that people would push.” The thing is, however, Coalhouse Walker, who sought recompense and repair (reasonably in the beginning, then violently) from racist white men for the damage to his property, a model T Ford that was a symbol of his wealth and status, was eventually killed by them.

Watching that white Ford Bronco speed along the highway followed by a squadron of police cars in June of 1994 (and later, the Time Magazine cover) reminded me how Simpson, like Bigger Thomas, had tested the comfort he enjoyed among white people, now ran out the clock on white society’s benevolence, and finally became what they believed and feared of black male bodies.

***

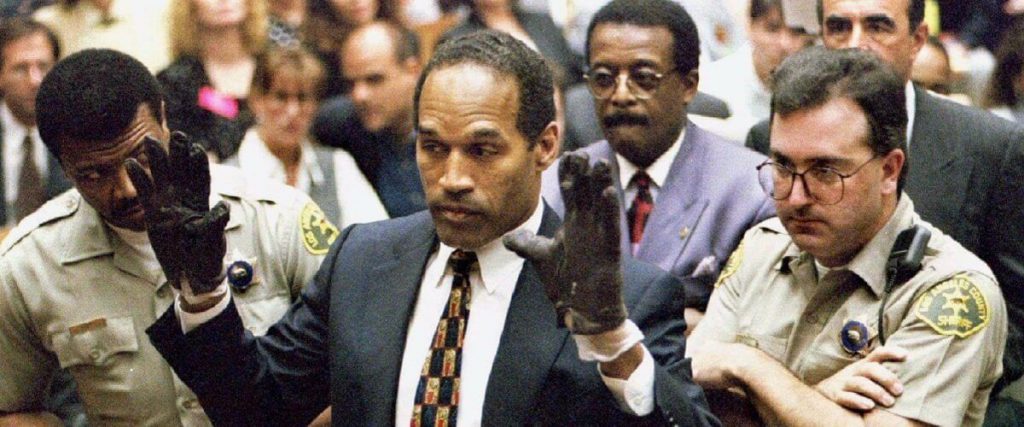

The striking thing about the concept of race for white Americans is that they simply believe it is something that just springs up on them whenever they’re in the presence of black Americans. The greatest trick. Like it was an actual playing card, shimmied up a high-priced lawyer’s sleeve waiting for some sleight of hand. Race is only a topic when black people point it out. Race is absent as topic or controversy among white Americans because they are firmly gripped in the powerful fiction that they are not raced, and this unique position is the delineation of normal. Everyone else is deviant. For the L.A. County DA’s team, as the LAPD itself, the intersections of race, class, gender compounded by the culture of celebrity blindsided them. Their case couldn’t ignore race, it was inextricable. Talk had already begun around building a case to discredit the LAPD’s evidence collection and the nefarious intentions of one cop. Detective Mark Fuhrman was flagged as a potential lightning rod within this context as early as the summer of 1994, when the defense team told the New Yorker’s Jeffrey Toobin that “Mark Fuhrman’s motivation for framing O. J. Simpson is racism.” “This is a bad cop. This is a racist cop,” they said.

In 1995, I was introduced to critical race theory through a survey course in American politics. It would be my first introduction to the tenets of intersectionality and it was taught to me by a black man, educated at Oxford and Columbia, with working-class Midwestern roots, a heritage he and I shared. I read Derrick Bell’s Faces at the Bottom of the Well. Bell used story to help deconstruct the degree to which racism is woven into the fabric of the legal system. Bell, who had been part of the generation that agitated for black civil rights decades before, had written previously about the unraveling of those gains. The conservative backlash began as swiftly as the last critical civil rights legislation was signed in 1968, nurtured under the Nixon administration and solidified by the time of the Reagan revolution. Working-class and poor black communities suffered under a radicalized caste system that worked assiduously to compensate for the newfound liberties allowed to black middle-class Americans. The first lady declared a war on drugs which translated to a war on poor black communities in practice, and Bill Cosby wore garish gauche ugly sweaters performing a kind of respectable and socially palatable black genteel (yet, fatherly!) fool weekly, and later lecturing on the pathology of black folk. (Funny how that shit worked out, huh?)

When L.A. County made the decision to try the Simpson case in downtown L.A., it was in direct response to their failure to secure convictions for the four police officers in the King beating that caused the 1992 riots. The harder truth to swallow is that it was a raced decision to begin with. Which is, to say, race had long entered the courtroom because each of the actors, judge, attorneys, defendant, victims, witnesses and jury were all raced, harboring a host of biases silent or pronounced. There were raced decisions prosecutors made when tapping Christopher Darden to second chair and cross-examining Mark Fuhrman, who would later gut the state’s case against Simpson by invoking his Fifth Amendment privilege upon re-cross weeks before the verdict.

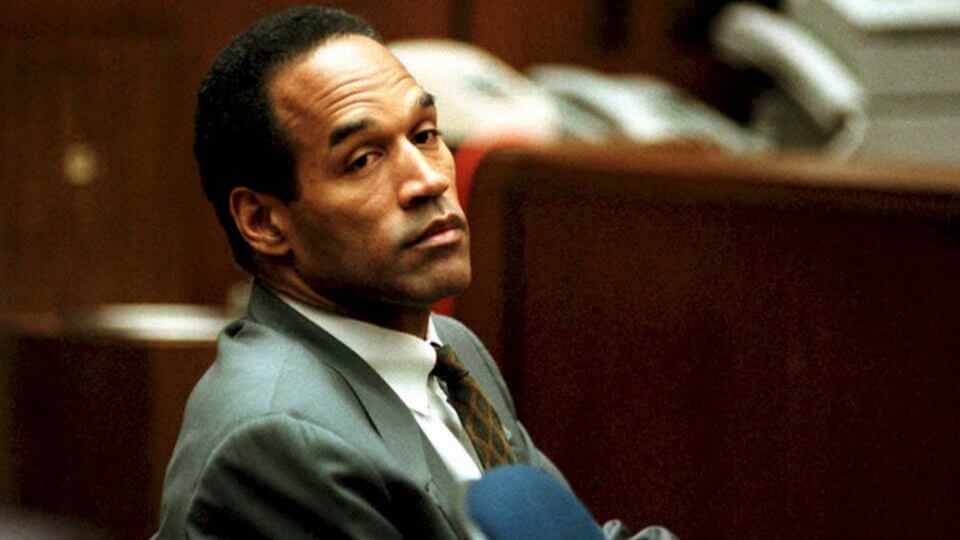

O.J.: Made in America affords us a clutter-free hindsight at this moment, a linear juxtaposition of Simpson’s defense team strategy, private conversations, the L.A. County’s DA team’s earnest and naive assumptions about the degree of racial animosity between law enforcement and black communities, O.J.’s trial notes, physical evidence, anecdotes from friends who were not witnesses during the trial, journalists, activists, former police officers, all assembling a robust portrait of a wealthy guilty man, who gamed the system.

The New York Times sought Derrick Bell out in 1995 to help explain the state of mind of black people to white America, who were reeling from the Not Guilty verdict, in the face of so much, as Marcia Clark put it, “blood evidence.” “Black people across the board, particularly women, tend to side with black men in trouble,” Bell told the Times. “They’re willing to convict if all the evidence is there. But there’s a presumption that there has been racist wrongdoing somewhere in the process. We saw it with Clarence Thomas and we saw it with O.J. Simpson.”

White America’s short and selective memory in these matters is critical in relation to black America’s very long memory. It is why a jury would eschew blood evidence.

I, too, cheered when the jury announced that OJ Simpson was acquitted of double murder. A miscarriage of justice with all the money Simpson could buy. When my white classmates asked what I thought, I simply said, “Now you know how it feels when a system fails you.” I didn’t give a fuck. Simpson, in the back of my mind, was guilty, and certainly not worthy of the particular kind of adoration he received from the masses of working-class and poor black people, a community from which he worked arduously to distance himself, ran to the arms of white acceptance. But he was a compelling proxy for the systemic imbalances in the criminal justice system that black Americans have articulated for decades; his life, Gatsby-esque right up to his fall, embodied all the things we observed about how whiteness and racism operated in American culture.

Yet, the documentary orders all of our narratives into a coherent whole. In some ways, it upends some of my rigidity around this case, and in others it challenges me to hold both my compassion and frustration in the same space; In reconsidering the spectacle of the trial and its players, as well as re-remembering the compassion I felt for the Brown and Goldman families. Now it seems so petty that any of us believed that justice for black communities could be found in the body of someone who tried to erase his identity. Or the question that inevitably follows: If you knew then what you know now, would you have cheered?

I equivocate. The answer falls on Maybe?

Still, I bristle watching archival footage of Fred Goldman’s (justifiable) frustration with the trial as he declares Johnny Cochran “the real racist” for pointing out racism within the criminal justice system. I did feel for him and I don’t think, now, I could ever ask him to understand the damaging effects of racism on black bodies and consciousness. But…

The Simpson trial really was the trial of the century because it told us who we were and who we weren’t. African-Americans so eager for a win amidst their pain accepted a perverse win over no win at all. Simpson repaid African-Americans for his newfound favor by doing some straight bullshit: posting up in Miami, performing as an outlaw—renegade—pimp, penning a memoir all but admitting to the crimes, never searching for his wife’s “real killer,” and later, commitment for armed robbery and kidnapping carried out to recover beloved personal trinkets. When you tempt fate like that why wouldn’t karma come and collect your ass? Really, bruh. In the 2005 edition of Native Son, the first line of the back cover reads, “Right from the start, Bigger Thomas had been headed for jail.”

Where, oh where, did he begin writing this novel of O.J. Simpson.

The powerful takeaway from O.J.: Made in America is an understanding how all of us process Simpson’s guilt within socially and politically charged environments: Los Angeles and its strained relationship with its African-American citizens; misogyny, overt and internalized; the obsession with celebrity and spectacle. The trial of the century was about us as Americans and the frayed parts, the intersections where we haven’t resolved our own shit.

Trials are constructed narratives where one hopes to arrive at the truth, then fairly determine the consequences. It would be ten years after the Simpson trial when I would serve as a juror on a criminal case, and the writer in me then could see how scrupulously selective facts work to serve the narratives between state and defendant. The Los Angeles DA team had a narrative in mind as they presented a case to a jury of people about whom they knew so little, and kind of, maybe, condescended to their frustration and anguish over a system that has repeatedly failed them. Hindsight has done little, it seems, to clarify for the prosecution the degree to which they honored or acknowledged that anger.

Edelman told Vanity Fair last month that one of the ideas from the film he wanted to show was that “the more things change, the more they stay the same.” There’s a surreal symmetry between yesterday and today that the film elides to be sure. Edelman later added: “I think the whole conversation that people—I would say primarily people not of color—have been sort of swayed by, or lulled into thinking, is that we’ve achieved a state of Post-Racial America because we have a black president. Well, that’s not correct.”

This month, the New York Times reported that Americans believe race relations to be worse in the final year of the Obama presidency than in the first, and as bad as they were in 1992, in the aftermath of the L.A. riots. Rodney King, forever haunted by his beating and its fallout, plagued by nightmares and flashbacks, drowned in his pool in 2012. “Some people feel like I’m some kind of hero,” he once told the Los Angeles Times. “Others hate me. They say I deserved it. Other people, I can hear them mocking me for when I called for an end to the destruction, like I’m a fool for believing in peace.” The summer after his death, the American media debated the criminality of a hoodie, in order to determine whether or not 17-year-old Trayvon Martin was responsible for his own murder.

You might also like