The Filmmaker and I, and You: Caveh Zahedi’s The Show About the Show

Directed by Caveh Zahedi

Opens March 17 at the Metrograph

Five years ago, at South by Southwest, Caveh Zahedi presented the world premiere of The Sheik and I, a film about a film: he had accepted a commission in the emirate of Sharjah, but the final product primarily documented his difficulties with censorship in a theocracy, and the threats of reprisals that followed. The Q&A was wild, with questioners angrily accusing him of recklessly putting his Arab collaborators’ lives at risk (Zahedi contends that this concern led to the film’s partial “blacklisting” in the US as well), and one even presuming to ask him, referencing his 2005 film I Am a Sex Addict, whether he was sleeping with the younger sound recordist and part-time child minder in the film. (Zahedi’s wife Mandy and toddler son were in attendance at the Q&A, as was the sound tech, if I recall.)

Zahedi’s confessional and video-diary films are based around an ethos of radical openness that extends even to a scrupulous attention to their own making—and makers. The Sheik and I would be incomplete without the moment when Zahedi says that, yes, “My films are the most important thing to me,” and, forcing his motives, conflicts and compromises (all of them!) out into the open as he does, Zahedi invites viewers to layer on more of their own. (“Caveh brought the whole thing up, not me…” is how Reverse Shot’s Nick Pinkerton ended his review of I Am a Sex Addict.) Zahedi movies wouldn’t be the same without the concentric rounds of second- and third-guessing spiraling outwards from his self-exposures—and The Show About the Show probably wouldn’t exist at all.

In this explicitly self-referential seven-part series, produced starting in 2015 and continuing up almost, seemingly, to the present, Brooklyn-based Zahedi pitches BRIC on a television show, to be concerned primarily with the issues that come up with its own making. Episode one features reenactments of Zahedi pitching the show to its producer (played by the local filmmaker Dustin Guy Defa), and subsequent episodes dramatize the artistic process and increasingly complicated personal fallout of the previous ones, through a combination of obvious and less-obvious fictional scenes and dramatic re-creations, presumably on-the-fly-documentary footage of Zahedi and home and working on the film with his crew, and Zahedi’s to-camera monologues against a black background, in which he freely, painstakingly, explains where we’re at. As in Nathan Silver and Mike Ott’s Actor Martinez, which also opens today at Cinema Village, and similarly concerns filmmakers willing to sacrifice a bit of professional image in the name of posing emotional and metatextual questions, there are not clear delineations between different “levels” of fictionality in the film (which Zahedi edited the film with several of his students at the New School).

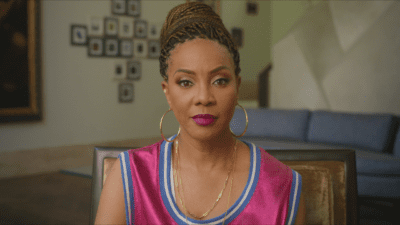

As in The Sheik and I, much of the drama emerges from Zahedi’s compulsion to bite the hand that feeds, in the form of sparring with his BRIC supervisors over standards and practices; with New School administrators over his sharing of a joint with his student production assistants (and his desire to use their H.R. meeting in the show); and with Mandy, a frequent presence in his filmography, over her finite support for his transparency, which extends beyond himself into their family life. Zahedi gets much dramatic mileage out of collaborators who prove willing to push boundaries, up to a point: actress Eleonore Hendricks and her boyfriend(?), aspiring filmmaker(?) Sam Stillman, bare themselves (physically, emotionally) for the camera, in scenes and re-shot scenes covering ethics in artistic partnerships—and, later, the fairness of those scenes. Sam is recalcitrant about reenacting his more erratic coked-out moments for the film, but not so much that he doesn’t ultimately (though we see the scenes before his reluctance to shoot them) also flaunt a volatile charisma, particularly his declaration that he’s Zahedi’s “David Mark Chapman,” which he immediately follows up with an offer of babysitting help, all delivered with a tellingly affected city-boy drawl.

Zahedi is obviously a purist about his work, pushing to render sex, drugs and raucous fights in ways that leave little cover to the participants—to the point of cruelty at times, as when he invokes his capacity for resentment to convince Mandy into shooting a scene. There’s a canniness to his shit-stirring, to a degree greater than I noticed in The Sheik and I, where I read his prods against content restrictions less as manipulation than as an innate reflex towards free and open speech, which he in his rigor must then account for by faithfully portraying it, and its methods and consequences, in the final film. But if I’m now more suspect of his motives beyond “an ethos of radical openness,” well, that’s because of what Zahedi left in the movie for me to discover.

And it certainly does keep the show moving, yielding emotional debates over art and love—Eleonore’s recorded-live reaction to some dailies is touching, uncomfortable, and thought-provoking—as well as glibly funny meta-moments revealing the process and compromises of the film: Mandy refused to shoot an oral sex scene inspired by a recent marital spat, Zahedi explains, which is why she’s eating a banana here. If that joke raises another layer of questions to be worked through, it’s just a byproduct of the process (and further complicated by Mandy’s goofy face-pulling in later outtakes…). Zahedi’s discussion of their marriage, frayed by resentment over the sharing of parenting burdens, and anchored by frequent pot use, is challenging in its apparent frankness: you question what right you have to watch it, even as it taps in to genuine insights into partnership (and art-making).

In addition to being a rare mix of raw and mindfucking, The Show About the Show is frequently quite funny: Zahedi is verbose, a fan of quick-cut insert-shot gags, and delightfully overplays his naïve obliviousness in the more obviously stilted reenactment scenes. There is, though, a latent meanness that occasionally surfaces, like the rare inadvertently scary hostilities in Woody Allen. When Zahedi sets up a scene by mentioning that the BRIC promotions team is, in his view, simply lousy at their job, the gratuitousness of the call-out is not mitigated by the cutesy sight gag that accompanies it. It’s a shitty way to treat people, incredibly casual in its solipsism, evidence of a worldview that troublingly prioritizes art-making above human considerations as if they’re separate things, and it’s killing me that I’ve spent so much time thinking about it, because it means that Zahedi was right not to cut it.

You might also like