Artists on Edge: How Sure is a Visa in Trump’s Brooklyn?

I’m sitting in offices of Frenkel, Hershkowitz & Shafran on 37th Street in Manhattan, which comfortingly look and smell of manila, trying to make the most of my lucky audience with what seems like one of the city’s busiest law offices. While immigration law hasn’t changed much in recent years, David Frenkel tells me, Texas-based U.S. bureaucrats responsible for approving (and increasingly, denying) visas have imposed increasingly restrictive interpretations on existing laws. “It’s become a far more complex field,” he tells me. “Where in the past a single immigration lawyer could realistically field everything from a simple employment visa to a political asylum case, now we have lawyers who specialize in every distinct category of the law.”

The material effect on foreign artists is twofold: it’s gotten much harder in the last five years to successfully attain many long-term visas and legal statuses; and many cases which might’ve been a “sure thing” in one year could be nigh-on precarious in the next. It’s often a coin-toss, I learn; your fate the providence of a bureaucrats’ rusty standards and unpredictable whims.

I met Frenkel through a girlfriend and several other foreign friends I’d made in Brooklyn since moving there in 2012. Of these, two Colombians comprise a New York indie pop act called Salt Cathedral, who make breathlessly pretty music with a Caribbean flare—an ode to the round-the-clock bump and grind that scores the street corners and restaurants of their adopted neighborhood of Bedford-Stuyvesant. A two-person outfit, Salt Cathedral members Juliana Ronderos and Nicolas Losada were born in neighboring sections of Bogotá, and are both here on what are called O1 and O2 visas, respectively, denoting “aliens of extraordinary ability.” Getting this visa is no small task, they tell me, and Frenkel confirms it—this was a tough one even prior to five years ago, when they first clinched it.

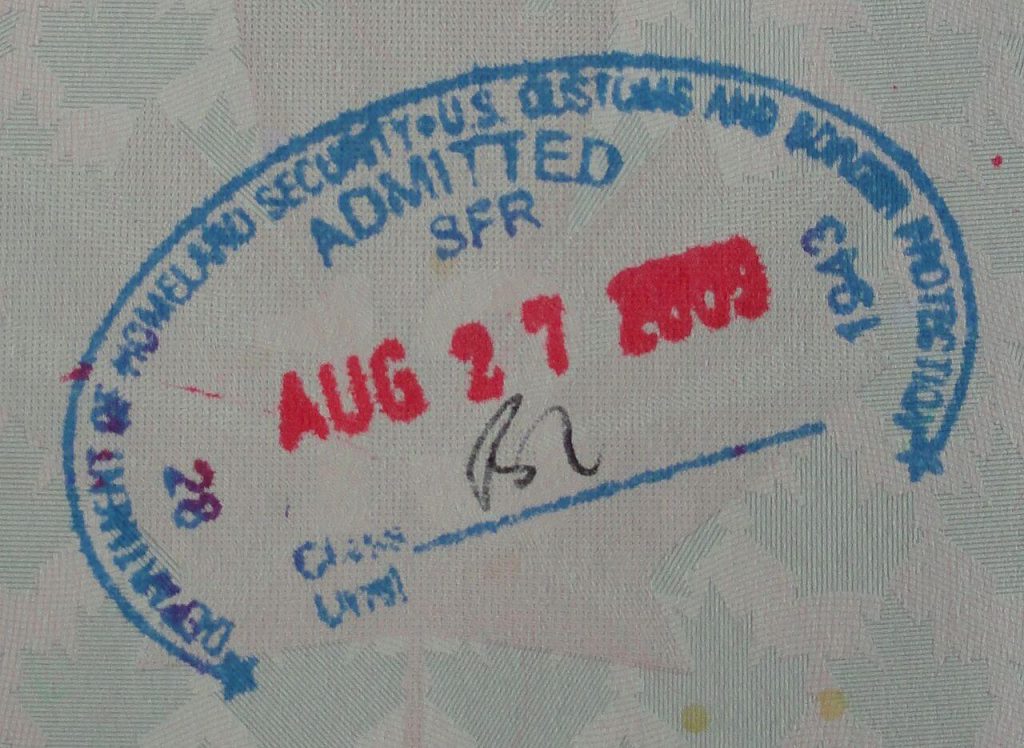

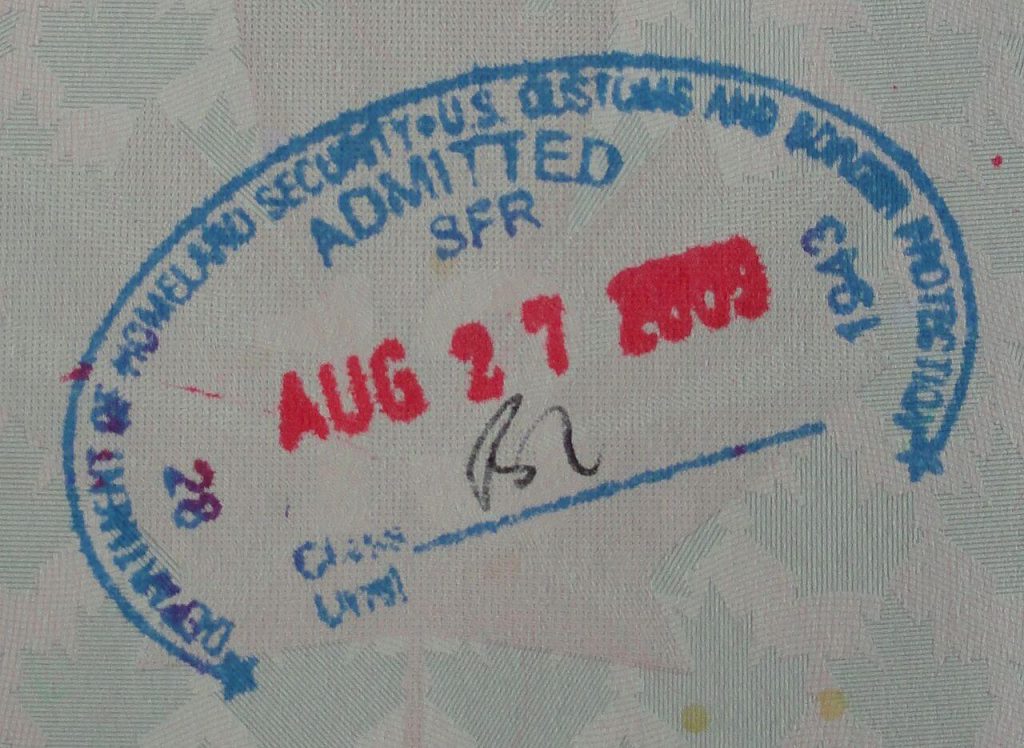

There are a number of different visa types, all with different requirements, stipulations, and privileges, determining the conditions on one’s “legality,” whether one can work, whom must “sponsor” one’s existence here, and under what conditions they could, quite suddenly, be made to leave. B1 visas, the most common, are typically granted for short periods, and for extremely limited business purposes, while J1 and H1 visas are much more common among New York’s younger crowds. While the J1 affords limited working privileges to younger college students, H1s (and H2s) are designed for foreign college graduates. Companies looking to recruit for a highly specialized skill might sponsor their prospective employees for an H1 (for a period of three years at a time, contingent on employment), while H2s are much shorter, seasonal visas for far less specialized work; duration and privileges granted according to one’s background, education, and skills.

EB-1 visas, by contrast, grant “permanent residence” on an employment basis to aliens who demonstrate “extraordinary abilities” in anything from business to the sciences to the arts. This is a much tougher get—doubly so for artists—and requires applicants to demonstrate “a level of expertise indicating that the individual is one of that small percentage who have risen to the very top of the field of endeavor.” While it’s by no means unheard for artists to pursue this visa, without making a truly seismic impression in their chosen field, the EB-1 route to permanent residence is next to impossible.

Many opt for the path of least resistance, if they can: a green card through marriage. While no one advocates the pursuit of a spurious “green card marriage” (government scrutiny on couples within the first two years of marriage is extraordinarily high) immigration lawyers often hold seminars stressing how mind-bogglingly tough permanent status can be to get, and how those with serious boyfriends or girlfriends have a real opportunity to cut swiftly to the front of the line if they feel personally and emotionally ready to take the plunge into “till death do us part.”

For a writer, a painter, or a musician, the O1 is a plum, three-year visa. My lucky Brooklyn friends—whose families had the means to commission Frenkel’s in-demand services—are thus credentialed exactly the same as British television personality Piers Morgan, or Canadian pop stars Justin Bieber and Drake, who may live and work here only in the musical capacity for which their O1s were approved.

Like Bieber, Juliana and Nicolas are not permitted to work or earn money outside their “field.” For musicians who make their living off anemic streaming royalties and meager gig fees, and with rents in Brooklyn wafting upward like a runaway balloon, this can be a particularly hard pill to swallow. Even a part-time job in the service industry to make ends meet is completely out of the question. For performers like Salt Cathedral, as well as the writers, painters, and even cooks who share their visa, it quickly becomes clear that the only immigrants who can really afford to “make it” here are the ones with prior economic privilege, or those whose industries quickly open up and usher them into the highest echelons of success.

Even trickier, some visas, like Nicolas’s O2, are much more provisional. His, for example, is entirely contingent on Juliana’s O1; without her, or if she were to be denied renewal, he would have to abandon his lease, his furniture, his recording and touring schedule, as well as his friends and the rest of the roots he’s placed here in the last eight years. His life, as Juliana’s, is dependent on the evolving—and narrowing—approach that the Texas-based USCIS (U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services) takes toward our country’s laws regarding who “matters” enough to live here, and whose entire existence should be suddenly upheaved with the flick of a pen.

Frenkel, initially a bit skeptical of my freewheeling interview (and my probably glaring ignorance in the basics of his profession), recalls fondly that he never meant to get into immigration, and soon eases into kvetching with me about the purgatories and frustrations unique to his field of the law. “I just sort of fell into it,” he tells me, “because I was the lowest man on the totem pole. But before I knew it, it had just sort of blossomed into a practice..”

David turns away far more clients than he can take—of this, he reminds me over and over. And of the clients his office takes on, many are so befuddled by the dozens of rolling hula hoops they’re meant to dive through they screw up some tiny, yet critical part of the application process, and risk being refused the visa they seek—one they may even have felt confident of receiving (or renewing) with ease. Many, too, remain in denial about their soon-to-be expiring visas, and only make a visit to lawyers like Frenkel with mere weeks or days left. There’s often little he can do for these people, he tells me. Without the huge amount of time needed to pull together a hearty-enough application, their chances are basically nil.

My friends might not have gotten their O1 if they tried again today,David tells me, reflecting on Salt Cathedral, former clients of his office. I quickly learn why: The Texas approval agency refuses to update its understanding of what constitutes a musician in this day and age. As such, it’s become almost impossible for many artists to ‘prove’ their relevance to a U.S. bureau which can barely understand anything more modern than a cassette sale.

“Music streaming figures” mean absolutely nothing to the USCIS, and if an artist can’t demonstrate a certain threshold of “record sales”—an increasingly meaningless concept in the digitally-dominant, Spotify-driven music industry, they’re likely out of luck if they try to shoot for an O1 these days. A bevy of press clippings delivered in print are given higher credence by the Texas evaluators, but such things feel downright old-timey nowadays, and oblique references (or even explicit write-ups) in influential blogs and websites will carry less weight, if any at all. Frenkel has even heard of instances where visual artists with prominent gallery exhibitions were told their achievements didn’t merit the requisite artistic relevance to sustain their continued legal residence in the country. Put simply: without a Nobel Prize or a Grammy Award, nabbing an O1 is an increasingly steep task for the scores of young artists whose dream it is to live, work, and create in the United States.

Later on, I’m sitting with Juliana and Nicolas in Contra, a trendy Lower East Side eatery whose tiny, upstart kitchen has recently netted a well-deserved Michelin star for their witty, creative interpretations of new American cuisine. One of the cooks is mutual friend of ours—another Colombian national with dual European citizenship, and he drops by our table to have us try another of the restaurant’s offerings—a tiny, modernist pile of brightly-colored shavings on a gleaming plate, more white-space than actual dish.

He sits, and I tell them of my recent interview with Frenkel. The conversation quickly veers to the almost absurd level of privilege enjoyed by the four of us. I, an American of wealth and blinding whiteness; they, Bogotá-natives with supportive and enterprising enough families to help them brave the miles of red tape required to live and pursue their creative dreams here, which seemingly only money can allow one to cut his or her way through to a happy, if always temporary, ending.

We’re sitting there in that restaurant, but it’s not even November yet. We toast to our privilege and forget about life for a little while, my friends each a comfortable year or two from having to reckon with a multi-circle of Hell visa process that lies in their future. “There’s an inhumanity to it,” our friend tells us. “You are scrutinized and interrogated and you wait indefinitely for an answer without explanation, positive or negative. Then you are always at the mercy of customs officials when you travel, and it can get disrespectful and undignifying. It’s what you sign for as an immigrant.”

But since that autumn evening, in the twilight before the November 8th catastrophe, and particularly in recent weeks, everything has changed, every immigrant’s latent anxieties and feelings of unbelonging revved into high gear. Tax-paying mothers ripped from their homes and their children deported to countries they haven’t set foot in in decades; academics and new hires from countries deemed “too Muslim” forced back onto planes at the border, their cars left stateside to rack up parking tickets indefinitely while the ACLU—if they’re lucky—sues to pry open the border just an inch, so they can squeak back in while they still might.

Lawyers, analysts, and opinion writers are baffled, stunned, with cartoon birds flapping around their heads. In these uncertain times, who will stand up for the immigrant? Who is ready to risk their safety for the student, illegally parried by a rogue Customs agent, operating under “direct orders” from the President; or the Uber driver, non-union, a “contractor” without a single protection from his employer, who has to worry obsessively over every speed limit, lest a chance run-in with a police officer—or worse, a random “ICE checkpoint”—could tear him away from his home and his family forever?

In Brooklyn, it happens more often than you’d think:

“Ah, so what country are you from? India? Which visa? I tried for that but got denied, and my student visa is about to expire, so I’ll have to leave. Unless I can get married, you know? The lawyer told me that’s by far the easiest way.”

Or, “I’m leaving for a month. Honestly not sure if they’ll let me back in when I come back.”

Are these questions you ask yourself when you make plans to leave the country on vacation? Or when you make plans more than 12 months in the future?

“Being an immigrant is getting scarier every day,” Juliana told me recently, as we discuss the quiet horror experienced by every immigrant, legal and illegal, in the month since the GOP took control of two whole branches of government. “Some people sigh with relief when I explain I’m from South America and not the Middle East. But the immigration bans so far are so arbitrary, and they could come after any of us next without reasonable justification – that’s the precedent they’re setting. There’ve been no terrorists from any of the Muslim-majority countries banned so far, so I doubt the real reason is ‘national security’.”

“I have been living in the United States and paying taxes for eight years now. If I’m scared, I can only imagine what it’s like for people who are undocumented or even green card holders who have been living here for many years, functioning as Americans, and now live in fear of getting kicked out and having to abandon their life as they know it. It’s unfair.”

Unfair or not, Salt Cathedral presses on with recording their debut record, and scores a minor Spotify hit with a surprise collaboration with Jewish reggae singer Matisyahu. They’re lucky—this could mean another O1 visa is in the bag, provided they don’t find green cards first, or don’t find themselves caught in the widening net of peoples the government considers “banned.” Our friend in the food scene takes a brief opportunity to visit London to design a menu, hopeful that he will be let back in—but he tells me he’s not willing to place any bets on it.

Doubtless lawyers like David Frenkel will see a more desperate deluge than ever in the coming years; already, as he is, at the point where he has to turn many cases away,. Many more still will be turned down for insufficient access to information, or another uncharitable revision to the bureaucratic interpretation of immigration law. The Trump Administration has dramatically expanded the already wide grounds on which it can expel people from the United States With cases of probable deportation, Frenkel told me, and unlike visa cases, his firm will often take on a client, knowing eventual deportation is the likeliest outcome. “Whatever you can do to simply prolong their stay in a legal fashion, it’s worthwhile, even though you know you’re ultimately going to lose the case.”

For all immigrants, documented and undocumented, life here will go on until, quite suddenly, it doesn’t anymore.

Banner image by Evan Romano

You might also like