The Troublemaker: Zetta Elliott and the Future of Children’s Literature

“I’ve been a storyteller a long time and I’ve been a troublemaker a long time too.”

It’s the third week of school and this is the first time I’ve seen this happen. Every single one of my fourth-graders is sitting up, eyes on the person speaking, enthralled.

Our guest today is author and activist Zetta Elliott. If it was her choice, Elliott would lose the second title. “Artivist is a term I’m more comfortable with,” she tells me later. But whether she likes it or not, activist is a label she’s been assigned by those who know her writing and advocacy on behalf of diversity in children’s literature.

“She is an activist in all the right ways,” says Michelle Martin, the Beverly Cleary-endowed Professor of Children and Youth Services at the University of Washington’s Information School. “She is not afraid to tell it like it is, even if people aren’t gonna like it.”

On this particular day, Elliott is in my classroom to discuss both her art and her activism. The students listen with wide eyes as she mentions the 23 children’s books she’s written — six in 2015 alone, and another five to be published by the end of 2016. Her latest, a picture book about the power of forgiveness and fresh starts called Melena’s Jubilee, came out this past November.

It’s clear Elliott has done this presentation before. She weaves her own story — growing up Black in Toronto with few Black friends, neighbors, or picture book characters — into an explanation of the overwhelming whiteness of children’s literature. In kid friendly language she summarizes Rudine Sims Bishop’s scholarship on the subject. As Bishop explains it, books should serve as mirrors, windows, and sliding glass doors.

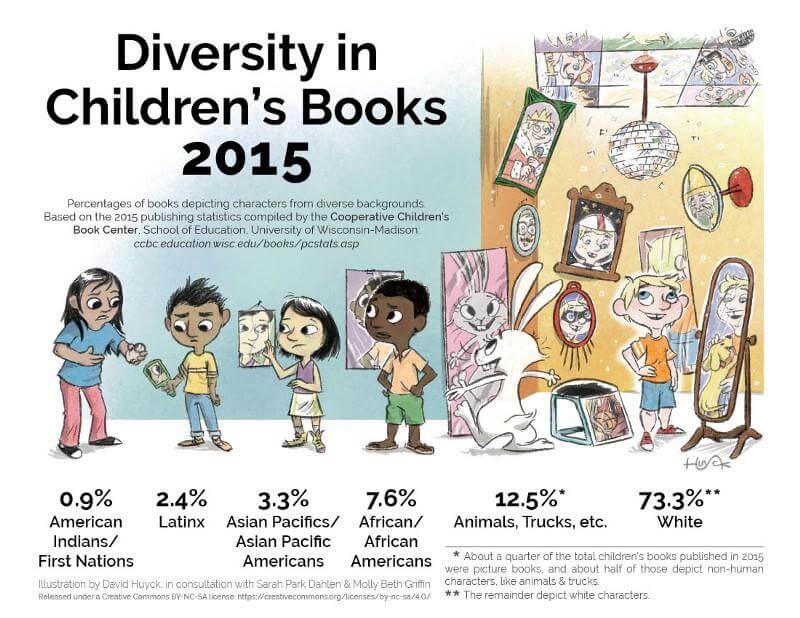

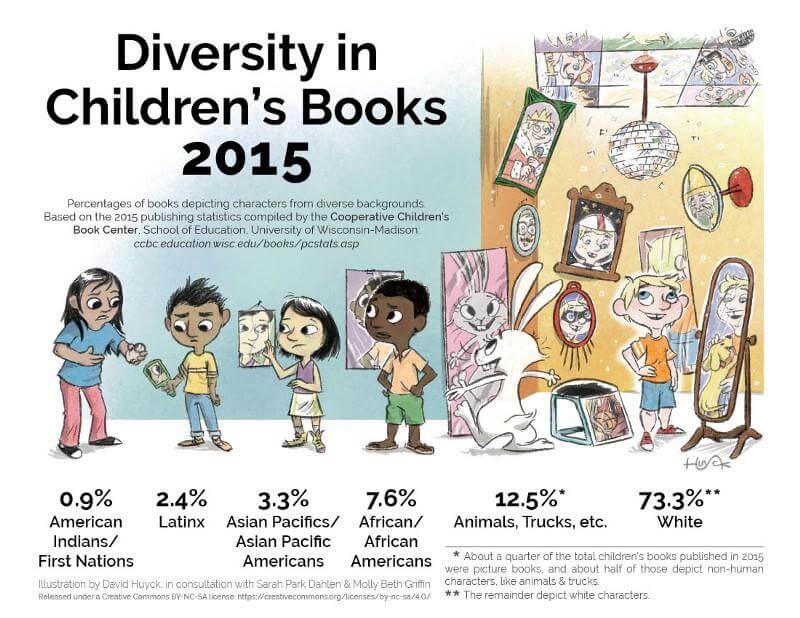

The problem is, Black and brown children like my Harlem students have far too few mirrors — books in which they find representations of themselves. Elliott makes no attempt to shield this injustice from my students. Together she and my students analyze an image based on the latest report on diversity in children’s literature by the Cooperative Children’s Book Center (CCBC) at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

All of this leads to a discussion to a book which — like all of Elliott’s work — she hopes might be the answer to this problem. Published by Lee and Low in 2008, Bird is Elliott’s most critically acclaimed and perhaps most personal story to date.

The story is heavier than what most consider picture book material. For that reason, Elliott had to fight hard with Lee and Low, who were more inclined to turn it into a chapter book (and thus present it to an older audience).

The story focuses on a boy, Mekhai, who longs for his older brother to get well. But he and young readers learn a tough lesson about the ways drug addiction can fracture individuals and their families. Is this really a book for kids?

It depends which kids.

The kids in my class share painfully earnest connections to Bird (a missing family member, a loved one addicted to drugs). But their honesty is fully reciprocated. Elliott shares the painful story of her own brother’s drug addiction. In less than 45 minutes in the classroom she’s created a space of trust and sharing that some teachers can’t cultivate in a whole year. It’s the kind of emotional resonance that powers her stories as well.

You won’t find most of Elliott’s books in bookstores. With the exception of Bird, Melena’s Jubilee, A Wish After Midnight (published in 2010), and Ship of Souls (published in 2012), all of her books have been self-published, which means few reviews and even less access to marketing. Elliott recently hired an agent in hopes of finding more publishing opportunities. And on November 22, Publisher’s Weekly announced that Random House had acquired her book, Dragons in a Bag. The book is not slated to be published until 2018, a timeline Elliott finds frustratingly slow. In the meantime, she continues to self-publish, intentionally making them available in paperback and selling them at affordable prices.

Elliott has lived in Brooklyn since 1994. “I do think I’ll have to move,” Elliott says in response to rising rent prices in her home of Prospect Lefferts Garden.

Elliott has spent the past two years as a writer-in-residence at the Weeksville Heritage Center. She will return in spring for a third time. It’s a role that perfectly blends her interest in preserving Black history (she has a PhD from New York University in American Studies), mentoring new writers, and her love for Brooklyn.

According to Weeksville’s Executive Director, Tia Powell Harris, Elliott is the kind of person Brooklyn should be fighting to keep. “If you’re in search of a newfound place, you have to start with what’s there. Part of the richness is people who carry the legacy, teach the legacy, and influence future generations, and Zetta is one of these people.”

Both the fight over gentrification and the struggle for diversity in children’s literature are about space existing for people of color. Elliott draws a comparison between white people moving into a neighborhood and “discovering” a restaurant or art form and non-Black authors telling narrow stories about Black characters.

As evidence, she cites When We Was Fierce, which was pulled by its publisher, Candlewick Press, after backlash over the use the author’s usage of manufactured Black slang. The fact that When We Was Fierce made it to bookshelves before prompting a storm of controversy is another testament to the lack of diversity in the publishing workforce.

Gentrification isn’t the only parallel Elliott sees to children’s publishing. She often couches her advocacy in strong terms: for example, talking about “reparations” for children’s literature. Likewise, she compares the publishing industry to a police force.

In both cases, Elliott says, the problem is cultural and systemic. For a book by or about a person of color to be successful it has to go through a process of being acquired, marketed, and reviewed.

“If we’re going to look at disparities we have to look at the people who are the gatekeepers,” Elliott says. The vast majority of people in the publishing industry are white women, as are librarians and teachers who might select her books for reading lists or read alouds.

Some people might consider Elliott impatient. Zetta has suggested (as did a publishing industry professional who spoke to me off the record) that she would have more success with publishing her work if she learned to play nice and put more trust in white editors and publishers.

“I’m really not interested in having a conversation with someone who’s not going to tell the truth,” Elliott says. “Everyone wants reconciliation without the truth.”

This is where the “activist” title once again feels appropriate.

The publishers and others admonishing Elliott to slow down bring to mind the white moderates Dr. King complained of in his “Letter from a Birmingham Jail” or at the very least contemporary white liberals who support the motives of #BlackLivesMatter while tsk-tsking their sense of urgency.

While publishers preach patience, the publishing industry seems more invested in lip service to diversity than radical change. Scholastic Reading Club recently partnered up with #WeNeedDiverseBooks to produce special editions of their monthly book catalog. And yet, in addition to the grim numbers recently published by the CCBC, there have been some messy, high profile missteps by publishers such as A Birthday Cake for George Washington, which Scholastic withdrew after protests about its happy-go-lucky slave narrative.

Rather than wait for an equitable publishing industry fully committed to racial diversity, Elliott is creating an array of stories that center Black children here and now. Some of these are fantastical, such as The Phoenix on Barkley Street and A Wish After Midnight; others such as I Love Snow (an homage to Elliott’s childhood favorite Ezra Jack Keats) tell everyday stories.

The next book Elliott plans to self-publish is Milo’s Museum. Elliott says it was rejected for being too “didactic,” but it’s in many ways the perfect analogy for Elliott’s work overall.

The story is inspired by The Colored Girls Museum in Philadelphia. It tells of a young girl who comes home upset from a class field trip. She doesn’t see any images of her community in the museum, so she creates her own.

“We shouldn’t have to wait for a special exhibit to see ourselves in the museum,” Milo says.

In the author’s note for Milo’s Museum, Elliott nicely summarizes the intentions of all her writing and advocacy. “I hope this book will inspire children in search of mirrors to make their own museums, write their own stories, and value those institutions that truly reflect our diverse communities.”

You might also like