Scene Stealer: Jessie Edelman

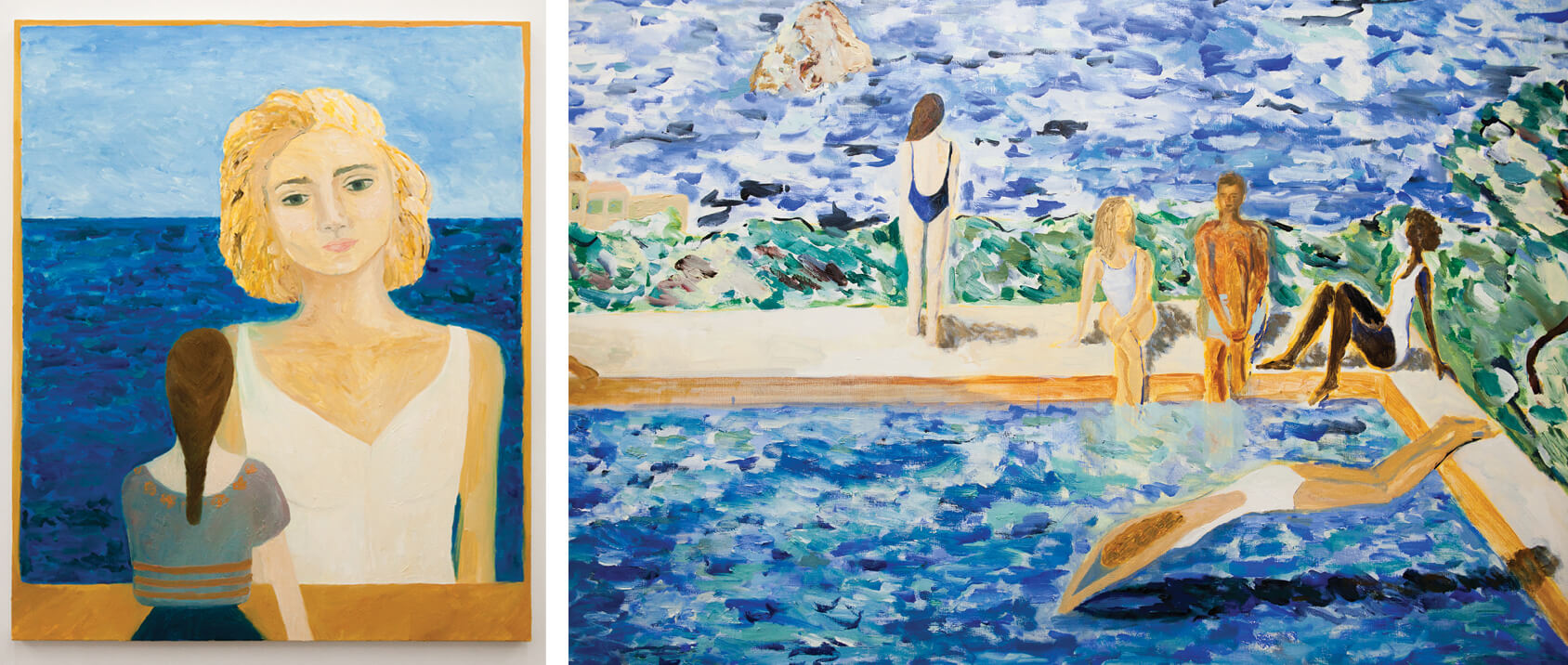

That same sweet, fiercely directorial framing tendency is a hallmark of Edelman’s paintings. Inside a careful, thin border, a starlet peers at another carefully painted frame, and inside that frame, a woman peers out again, but this time her gaze terminates on a bright blue ocean: it’s the Land O’ Lakes effect, perhaps better known as mise en abyme. Edelman harnesses that sense of long-looking—a sort of frozen stare—and turns it into a wistfully impressionistic world of repeated gazes.

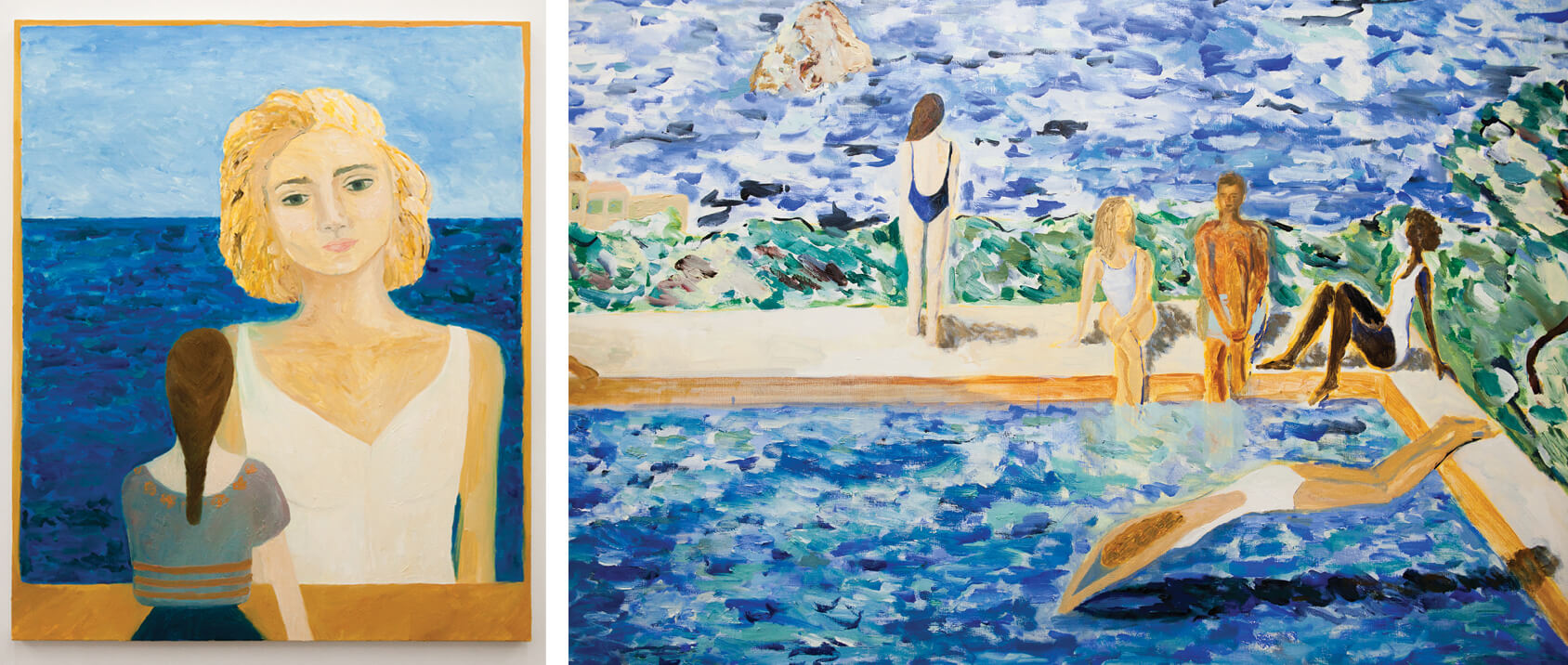

Edelman imagines the work in Stills from “The End of Summer”, her solo show open through October 16 at Denny Gallery, as snapshots from a film she might direct. There’s an establishing shot of everyone swimming, a closeup of the star, and an aerial of two best friends floating in a cove. In nearly every frame, the master-viewer, a shadow of the painter, is as omnipresent as a voiceover.

Born in Milwaukee, Edelman attended Skidmore and Yale. She now lives in Fort Greene but keeps a studio in Bushwick. We met just after she finished installing the show, and her cheeks were flushed from early September heat; her curly hair tumbled over sparkling green eyes. “Hi,” she said. “Sorry I’m late.” We embraced.

Just kidding! She wasn’t late and we didn’t have a steamy embrace. That’s what happens in the movies, or in paintings. But the rest of this—a snapshot of our conversation—is true.

BK: It feels like none of your figures really exist in the same space—even in paintings where people appear together, no one is loudly together. Except maybe in the largest work.

JE: Yeah, I do feel like my figures end up looking like sculptures, and I want the figures to be in their own heads or own space. The most interactive is the group of figures talking together [the largest work], but I intended to do that—I felt like my figures were so isolated, and I wanted to have a group that was talking together.

I do feel like in some of the paintings, people have a certain tension—you feel as if something psychological might be happening. Or, for me it’s unclear if there’s some psychological tension between the figures. I wonder.

It does make sense in that larger work, because everyone is convening.

And I do feel like in some of the paintings, people have a certain tension—you feel as if something psychological might be happening. Or, for me it’s unclear if there’s some psychological tension between the figures. I wonder.

Like the man watching the woman in that smaller painting, in the back room [The Object of My Affection].

Yeah. When I thought about the female gaze in terms of this series, I decided I should also paint the male gaze. Why not?

With that painting, “The Object Of My Affection”, I wanted to paint a traditional male gaze, with him looking at her. And I feel like the scale makes sense for them to be in a real space. I wanted to play around with something that seemed traditional to me.

She’s kind of like, whatever. But is it a real space? Is it not a real space? And I really wonder what’s going on with them—are they in a fight? Is he leering after her? Does she even know if he exists?

Is he working at the hotel and just staring at her?

Right, do they know each other, or are they just strangers? Does she even know if he exists?

Can you talk about the water in your paintings?

I think about the water as a painting space. [In the largest work] I was imagining that the whole painting frame had tipped down, and became the pool, and it was a painting within a

painting. And so the water for me is a very abstract space.

I like the idea of the figures reaching inside the pool, as if they’re physically reaching inside a painting or walking into the space of the painting.

When I was at Yale and Rob Storr was the Dean, he gave a

lecture and he talked about Cezanne’s painting of the bather, and it’s a painting of a man who’s stepping forward, as if he’s stepping out of the picture frame. I remember Rob Storr talking about him as the first modern painter, or what could have been the first modern painter, because the frame, or plane, is broken. And when he said that, I thought, how could I step into a painting? How do I turn around and go inside the painting, as a painter?

You might also like