#NYFF 2016: Paterson and Gimme Danger

Gimme Danger played October 1 and plays again October 3 as a special presentation of the 54th New York Film Festival. Paterson plays October 2, 3 and 16 within the NYFF main slate. Gimme Danger will be released theatrically on October 28; Paterson on December 28. Follow our coverage of NYFF 2016 here.

Gimme Danger played October 1 and plays again October 3 as a special presentation of the 54th New York Film Festival. Paterson plays October 2, 3 and 16 within the NYFF main slate. Gimme Danger will be released theatrically on October 28; Paterson on December 28. Follow our coverage of NYFF 2016 here.

Jim Jarmusch has long fulfilled a cultural role we don’t talk about in the mainstream, something we leave more to cool older siblings, one-time romantic partners and friends we didn’t get to know as well as we should have. That of the curator. He’s been a curator as long as he’s been an artist, someone who presents without ego the art that shaped him, that made his upbringing in Akron—and later the bombed-out, roaring silence of Ed Koch’s New York—not just tolerable but exciting. When Eszter Balint gets off the bus in the opening act of Stranger Than Paradise, before she asks for directions or situates herself in any meaningful way she hits play on a cassette deck and out spills “I Put A Spell On You” by Screamin’ Jay Hawkins. This is her passport, and Jarmusch described what it meant to be an immigrant as well as any American. He was a man from nowhere, who had only the culture he learned from to turn a dirty unfurnished room into a home. He fled his Ohio home to become a poet in Chicago but his love of film and fiction brought him elsewhere. Wherever you go, art will be the roof over your head. Look no further than his 2003 omnibus feature Coffee & Cigarettes (a movie that basically defined cool for me and my friends when it was released) for a quantifiable distillation of his virtues as a curator. Every ten minutes a new set of figures appear, hinting both at Jarmusch’s past work and/or the work of the creators who made them popular. I didn’t know at the time that placing Alex Descas and Isaach de Bankolé in the same cafe meant evoking Claire Denis. Jarmusch let us in the audience do that work ourselves. And in the process we learned, as he did, about the great wide world of cool, one shibboleth at a time. You can see it in his use of the music of Boris in The Limits of Control, which he then learned to emulate in his own band Sqürl (a name that comes from a joke Cate Blanchett tells in Coffee & Cigarettes), who are all over the soundtrack to 2013’s Only Lovers Left Alive and 2016’s Paterson. His love only gets sharper and more focused as you grow to know his art.

Jarmusch collected other misfits professionally, and projected them onto us through his stark, lovely compositions and patient, lonely sound design. He dropped names like Nikola Tesla, Jean Eustache, Junior Parker, Mike Hammer and William Blake throughout his filmography like living annotations. He was spreading his wealth of information, hoping to entice people like me, watching his films in dark basements or sparsely attended arthouses; just excited to learn about what was waiting for me on the other side of 100 minutes.

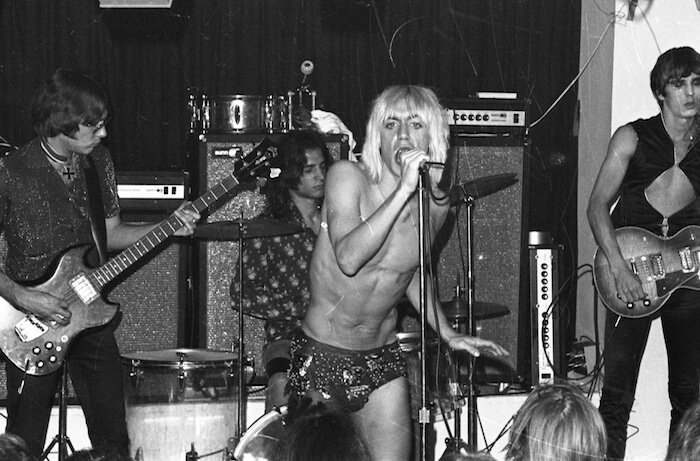

Despite his curatorial nature, he almost never makes documentaries, preferring to liberally spread his love for obscure cultural figures throughout his fiction. His last doc was the beautiful, expressionistic Year of the Horse on Neil Young. His latest is Gimme Danger, a hyperactive look at the brief, fragmented history of Iggy Pop and his band The Stooges. In Jarmusch’s eyes, they were the best rock band of all time, and by any measure they’re among the ten or twelve most important American bands ever. It’s a tough legacy to grapple with, when almost all of the work was done through osmosis. They permeated the ground water of rock and punk, which is a tough thing to explain cinematographically. So all that remains are anecdotes, not that they aren’t important and heartbreaking.

Gimme Danger is thorough enough considering the anemic sources left. Singer Iggy Pop (born Jim Osterberg) and James Williamson, one of a few guitarists the band once played host to, are the only living members of the once formidable garage-psych outfit. Naturally their stories are valuable and formidable, but they offer only pieces of the shattered puzzle. Jarmusch takes Iggy’s recollections and sets them to many, many different kinds of visual accompaniment: sped-up concert footage from the band’s heyday, clips from old movies, tv shows and industrial shorts, stock photographs, personal pictures of the band’s history. It’s a dizzying amount of stuff, only about half of it tuned to Iggy and the Stooges’ singular frequency, a mix of old school horror, Timothy Leary and lazy TV memories.

Jarmusch’s mixing of all these elements is certainly not without precedent, but his rhythm here feels a little off, a little too jittery and silly. It’s one thing to have Bill Murray’s confused bachelor turn on the TV in Broken Flowers and find an old WB cartoon about the stork delivering children, but it’s another to manipulate cut-out heads of Stooges rhythm section Ron and Scott Asheton in a Terry Gilliam-style animation of the band’s early hellraising days. We accept, in his fiction, the coincidences he provides in movies and tv as mirrors of his protagonist’s psychology. We live through our reference points and Jarmusch always zeroed in on that. But when they’re the only thing bouncing off Iggy’s stories of the band’s early days, it’s not enough to get a grammatical foothold. Gimme Danger is a little crazy and too fast to feel like classic Jarmusch, like he had a couple of funny ideas he’s never tried because they’re outside his stylistic wheelhouse. It’s still a fine and funny work about a few mixed-up kids who changed history, history now written all over their wrinkled, liver-spotted skin.

You just know how much Jarmusch feels kinship with these men and their weathered hands (fans know he’s used Iggy Pop as an actor in Coffee & Cigarettes and Dead Man). The director is 63 years old now and only just getting to the part of his career where he can let go of narrative and start to tell his own story in more than just his interests, though they’re also here in earnest. Paterson, his other film playing this year’s New York Film Festival, is about a young man who wants to be a poet, but seems overwhelmed by the signals life sends him.

Adam Driver plays Paterson, a bus driver in Paterson, New Jersey, who like his hero William Carlos Williams (author of a book entitled, wait for it… Paterson), is also a poet in his daytime. Jarmusch fills the film with his usual panoply of cultural icons, all Paterson natives at one time or another hanging on his local watering hole’s wall of fame, that device itself a nod to Spike Lee. Every day Paterson drives past Lou Costello park, hears kids (including Kara Hayward and Jared Gilman from Moonrise Kingdom) talking about Gaetano Federici or Hurricane Carter in the back of his bus, and ends up underneath pictures of famous natives and happenings at the bar, including when a local girl’s club named Iggy Pop sexiest man alive in the early 70s. His wife Laura (Golshifteh Farahani) tells him she wants to buy a guitar so she can be a country singer like Patsy Cline, and takes him to the movies to see Island of Lost Souls. Twins, a pet metaphysical theme of Jarmusch’s, start showing up everywhere after Laura says she had a dream about them. And when he has time, Paterson writes poems (writer Ron Padgett pinch hitting for Driver) and staring at the Passaic River’s Great Falls for inspiration.

Narratively speaking, Jarmusch telling the story of an aspiring poet is about as personal as he gets (though you can certainly see something of him and his life partner Sara Driver in the uber cool vampires at the heart of 2013’s Only Lovers Left Alive), and Driver does a remarkable job filling the Jarmusch hero with a very current set of motivations that allow him to strip himself down to essentials. The picture of Driver in military dress on the bureau explains his stillness, his willingness to accept minor confusion and turmoil if it means his life can stay on course. It also explains the smile on his face even when he sees his wife making plans and getting excited for life events he clearly can’t visualize. She’s excited by life, he’s content to coast. She loves and supports him, and he does too in his own way, but there’s an emotional language barrier between them. They’re never in the same register. Laura is constantly painting their house and her clothes different patterns in beautiful black and white, changing their environment every chance she gets. Paterson is more content to observe what he’s got. The light on a chess board sitting in beautiful, half-chiaroscuro on the bar, the foam at the top of a glass of beer, the boots of construction workers swapping stories about girls they didn’t make it with, his mailbox, always slightly askew. Paterson, like Jarmusch, sees delicacy and fairness radiating from every accidental form and overheard conversation. The world at rest, the same one he’s been filming since Stranger Than Paradise, lays claim to a calming disorder. The streets of Paterson, NJ look just as splendidly ruined as New York, New Orleans, Detroit and Memphis did when he let his camera find them in the past.

Jarmusch has always been known for his almost zen-like mise-en-scene, the studied calm of his pacing, the way he allows dead air to make both his comic beats and dramatic payoffs all the richer. By removing all but the faintest hint of a plot from Paterson, he’s returned to the laconic prose he used in his first features Permanent Vacation and Stranger than Paradise, and found himself a more patient, observant person, one willing to use close-ups and inserts to help us see how remarkable the ordinary can look. He’s still providing help for emigrants from childhood by showing that the world is full of gravitational forces and each can look mighty seductive, but it’s also ok to follow your own path. To love everything you see without letting it change you. Paterson is one more guide for young cinephiles to help center themselves, to start their journey towards finding their identity through art. Jarmusch found himself a long time ago, and has been sharing in the euphoric moment of discovery ever since by putting together the work that so inspired him in a neat, slightly rusty lunchpail like the one Paterson carries to work every day. The world is still hard on Jarmusch’s dreamers, whether an aging rock star or a bus driver with a notebook, but he’s always known how wonderfully kind it can be, too. Paterson is one of the warmest creations he’s ever given us, but with any luck he’ll never stop showing us what’s cool.

You might also like