Where Memory Lives: A Q&A with Jacqueline Woodson

The first book I saw myself in was Jacqueline Woodson’s If You Come Softly. I’d sit and relax into her words, breathing them in, over and over again, letting them heal the parts of me I didn’t know needed healing. As a curious thirteen-year-old, Woodson’s beautifully crafted and heart-wrenchingly honest work made me trust that there would be more words, more books, that would help guide me. Through what? I wasn’t sure.

Over a decade later, after reading the National Book Award-winning Woodson’s latest novel, Another Brooklyn, I found myself feeling, yet again, heartbroken and satisfied, questioning and in awe, confused and whole. In her first adult novel in twenty years, she uses her powerful prose to create moments that force you to remember to breathe, moments that beg you to rest, and moments that tell you to relax into yourself. By letting readers navigate the blank spaces, physically and figuratively, Woodson helps us slow down and reflect on what came before, and what comes after.

What I didn’t know when I first read If You Come Softly is that time is fleeting. Moments end. Pain and happiness subside. What I didn’t know then—and what Another Brooklyn, about an adult woman reflecting on her 1970s Bushwick adolescence, depicts—is that power and individual grace comes from the things we carry with us into the next moment. The things we choose to bear, and the things we choose to believe, become a part of who we are.

“We were on earth, heading home to Brooklyn.”

Tell us why Brooklyn, and writing a book for Brooklyn, was so important to you?

Jacqueline Woodson: I love Brooklyn. It’s important to put it on the map in a way that is both historical and relevant. A lot of times, for transplants and people who don’t know the history of Brooklyn, they just kind of come and take it for granted, like it’s this place that’s all about now. But there was a nuance and texture to it that, for me, felt worth remembering.

“Their cars and vans and trucks parted the brown boys, signaled right at the corner, and left our neighborhood forever.”

You dedicated this book to the memory of Bushwick, specifically the years 1970-1990. Are those the years you lived there?

No, I lived there from 1968-1981, but those were the years before it really started changing. In the nineties people started getting pushed out of Williamsburg and moving to East Williamsburg, or whatever they renamed Bushwick that was a lie. It was also when a lot of people started leaving. White folks had left Bushwick in the seventies and eighties, and then new white folks came back in the nineties.

“Little pieces of Brooklyn began to fall away. Revealing us.”

Another Brooklyn depicts the flip side of gentrification, white flight. What do you think of the changing tides of Brooklyn today?

I don’t know what’s going to happen. We were living the high life when 9/11 happened, and then people were fleeing New York like it was the plague. Now, New York is getting more and more expensive, and people are having a harder time living here. I grew up on Madison Street and, in the seventies, the city came in and planted these saplings. Now it’s this beautiful tree lined street. When I grew up it was predominantly black and Latino, and now it’s probably about a quarter white and not so much Latino anymore. It’s interesting to see what it keeps becoming.

Does that upset you?

It does make me sad that it’s a place people don’t have respect for. Even living here in Park Slope, you look at Paule Marshall’s [1959 novel] Brown Girl, Brownstones and all the Caribbean people who came to the neighborhood with the idea of working and buying a home. They bought these grand brownstones, and then they either went back to [the Caribbean] or they lost them somehow. And that loss became someone else’s gain—I’ve watched Park Slope go from this diverse neighborhood to this very not diverse neighborhood. I get that fear for Bushwick. But I also feel like what’s going to happen is going to happen, so what do we do with that? For me, it’s putting that history down so we know that it actually was.

“Who hasn’t walked through a life of small tragedies?”

After writing so long for children and young adults, why did you decide to write a book for adults now?

After Brown Girl Dreaming had so much success, I didn’t want people waiting for the next Brown Girl Dreaming or the next great young adult or middle grade novel. I didn’t want to paint a Starry Night again. I wanted to step out of that world and talk about something on a different level, and that’s not to say a deeper or a less deep level. What I really wanted to do was go in and get more implicit and experiment with the writing style. With Another Brooklyn, I use more vignettes. It’s playing with how memory impacts us. I wanted to see what it was like to write from the other side.

“It must have felt like a beginning, an anchoring.”

After writing Brown Girl Dreaming, a memoir, was it hard to shifting your focus back to fiction?

It was, and that’s why one of my main characters in Another Brooklyn is the place, because the place is not fiction. Bushwick is real. I was intentional about making it a place I knew. Even though the characters are all fictional, every aspect of what I talk about, in terms of talking about Bushwick, is true.

“When I grow up. When we go home. When we go outside. When we. When we. When we.”

Time plays an important role in your book. What was it like to write a character that has to grapple with understanding that we don’t control time?

For me, getting older and watching my kids grow up and watching the world change, it feels like it’s happening faster and faster. For my 8-year-old, it’s not. My grandmother, who I’m sure wasn’t the first one, was always saying that time waits for no one. I always got annoyed when she said that when I was a kid, and now I completely get it. I really wanted to slow time down [in Another Brooklyn], but even as I was forcing it on the page you can still see it moving so fast. [When protagonist] August and [her friend] Sylvia meet on the train, time drops away completely.

“This is memory.”

In Another Brooklyn you explicitly call out memory. Why did you feel the need to identify it directly?

What I was trying to do was have August understand her space and time. If someone comes along and says “It didn’t happen like that,” what she is saying is “This is memory. This is my experience of that moment.” August repeating that again and again is about her owning it and saying, “You know what? You can’t take this from me. This is mine.” You see her telling some really painful moments, stepping back from them, and saying “This is memory.” In the very beginning of the book, she says “What is tragic is not the moment, it’s the memory.”

“That year, every song was telling some part of our story.”

Music, specifically jazz, comes up over and over again in Another Brooklyn. How has music affected your writing?

Whenever I write, I put my headphones on and I’m gone. It depends on the book, so when I was writing After Tupac and D Foster it was all Tupac all the time. When I was writing Behind You I was listening to a lot of Stevie Nicks and Fleetwood Mac. When I was writing Another Brooklyn, I was listening to a lot of music from the seventies, so “50 Ways to Leave Your Lover” comes up, “Rock the Boat.” I knew I was going to weave it together to eventually talk about jazz. But I didn’t listen to jazz until the end. That’s when August says “If we would have had jazz, we would have known that our life was going to come together this way.” Towards the end of the writing it was all jazz all the time: Monk, and Coltrane and Nina Simone.

Before I started writing I was thinking of the number four, and how many girls it was going to be [in August’s teenage friend group]. At one point it was just two, and then it was three, and then I was thinking about the four girls murdered in the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing, and what if they had grown up? Then thinking about Nina Simone’s “Four Women” and [the lyric] “my skin is black,” I knew it was going to be four girls. Nina Simone’s song is on my playlist along with a couple of songs from Sweet Honey in the Rock, my friend Toshi [Reagon]’s mom’s band. I was thinking about the Civil Rights Moment, the girls who would have become teenagers and who would have become women.

“I held on to my body and my brother held on to his faith, finally pulling my father back into it.”

You’ve written before about different religious traditions. Why was it important to you to explore Islam in this book?

I always felt that the Nation of Islam got a bad rap. My family was Jehovah’s Witness, but my uncle came home from prison having converted to the Nation of Islam. We grew up with both religions in our house, and I’d see people laughing about the bean pies, or the guys on the corner. It wasn’t understood that someone’s faith goes so much deeper than the joke you can make of it. I’m constantly thinking about people’s need for faith, and what are the situations that move them toward finding faith. There’s the scene where right after the Nation of Islam brother says to August, “Your body is your temple.” They are on their way to church, and she sees this white Jesus. She’s thinking about how god gave his only begotten son and what did he give his daughters? That juxtaposition of god and all this maleness and “my body’s my temple” and “who am I?”? I wanted to talk about what it means to have a deep faith not only as her father and brother do, but also to question it as August does. She is able to put it on and take it off. Even with the hijab, she covers her head at home and she goes out [without it]. She’s also taking a lot of it in and understanding her family’s need for that faith.

There’s an assumption of Christianity in our society that’s really dangerous, or even of Judaism, this idea that “This is who we are.” I remember when I was in Iowa, and this woman kept saying, “We’re all Christians here,” and no, we’re not. We come from all different faiths and all deserve a deep respect. After Farrakhan, people started disrespecting the Nation of Islam in a way that didn’t account for the fact that people deeply believe in this. Who are we to say that this is a lesser-than faith? It felt so much a part of the story because the Nation of Islam temple is in Bushwick. I wanted to talk about how everything is encompassed in the faith, from what one eats, to how one prays, to who one loves, to how one walks through the world.

“The four of us sharing the weight of growing up Girl in Brooklyn.”

Do you think growing up as a female in Brooklyn is an act that requires a specific kind of guidance?

I think definitely it does, even more so for girls of color growing up in Brooklyn. I’m saying that from the point of view of a mom, from someone who walks the street as a person of color. My daughter is fourteen, and I’m constantly talking to her about the guys hollering at her, but she doesn’t hear it because she has her earphones in. She’s a little bit more protected in some ways, but there’s still the gaze, and there’s that underlying rage. She was showing me all the #maninism posts on Instagram, which are ridiculous. We have to teach our daughters the history of feminism so that they have the tools to be able to talk about this with people who are anti-feminist or anti-affirmative action or anti-any of the things put in place to make life a little less rigorous for us.

“We saw the lost and beautiful and hungry in each of us. We saw home.”

You beautifully celebrate and thoughtfully construct female friendship in this book. What has the role of female friendships played in your life as a writer and a woman?

As a writer I’ve had a village, and the village is all these people I’ve known for at least twenty years who have helped me raise my children, who’ve been there for me as a writer, when I’ve just needed someone to go out to coffee with, when I needed to whine about the publishing industry. When I gave birth to my daughter, my partner was still doing her medical residency, and I remember people coming by and holding the baby for five hours so that I could be human again or have an adult conversation. I never felt isolated, and I’ve seen people feel this deep sense of isolation as new moms. That’s heartbreaking to me. [My village] comes from trust and it comes from recognizing that family is both biological and chosen. My relationships with women—and even men—in my life have been both so necessary and so appreciated.

“She told me to keep my nails long.”

August’s mom is hell-bent on her daughter understanding that women should not be trusted. Why was it important to show the kind of sisterhood and solidarity shared among women in this text?

Feminism for people can sometimes be more of a theoretical concept than a realistic and necessary one. People think they can be feminist and not have female friends, or can be feminist and be anti-women, misogynistic. You look at stuff like the constant hateration of everyone from Kim Kardashian to Beyoncé to Azalea Banks and then the same kind of hateration not paid to men. There is this disdain that’s coupled with a jealousy and competition that is so not necessary. As we talk about feminism we can forget what the true meaning of feminism is, which is that we are sisters in the struggle, no matter what our economic class or race or sexual preference or gender. Coming back to Park Slope, you see nanny’s pushing babies and you see people kind of looking at them as other. No, these are women raising your children and they are human and this is their job. They want equality as much as you do and they struggle with their husband just as you do and they want a good education for their kids just as you do. Trying to come to that playing field where we all see each other as 100 percent human is a struggle for people sometimes, but it’s necessary.

“We were safe inside our brown skin.”

Your characters grapple a lot with safety in both the internal and external sense, how does your understanding of safety impact the characters you write?

It’s so interesting because [in the seventies] with the [New York-based serial killer] Son of Sam, he wasn’t killing black women. It was one of those rare times when black women could feel safe and could actually go out at night. As tragic as it was, there was some safety. The outside gaze sees [black women] as tragic and even talking to white journalists about Another Brooklyn and hearing them talk about the poverty and the tragedy, it’s like, no. They were actually okay. For these four girls, when they are together, they are a human shield against the world. I talk about how boys didn’t understand girls together, what they understand is girls apart, covering their chest and the shame. There was a safety in their friendship and there was a safety in them living in a very brown place, walking through the neighborhood when all of this stuff was happening and not being threatened by it.

“We thought we knew.”

Was there an event or a certain point you felt you reached in order to write this story? How long have you been working on this?

When I started Brown Girl Dreaming, I had this plan of writing down everything I remembered from my childhood. When I got to the point of asking my mom what she remembered, about six months into the year I was writing the book, my mom died suddenly. I realized she wasn’t there to ask anymore, among other things. While writing Brown Girl Dreaming, my uncle had passed away, my grandmother had passed away, my grandfather, my aunt, my other uncle, and I realized that all these people who had gotten me to this place had become ancestors. And I felt like as ancestors, writing that book, I was in the room with them. I never felt really isolated as a writer. I felt like they were all saying, “Yup, this is the story you need to tell now.” So when I stepped outside of that space and later on began writing Another Brooklyn, I really wanted to speak more to what it means to lose and then gain. When someone dies you do gain a wisdom. You get older and more informed to what it means to be living and to have moved on to the next place.

“Death didn’t frighten me. Not now. Not anymore”

Another Brooklyn is as much a book about reconciling with death as it is about friendship and coming of age. What made you want to write about and explore death?

August is an anthropologist [studying global death traditions] who spent her life denying death. It makes sense, as an adult, to begin to try to understand it. The thing that comes with knowledge is a power, and so now she has this power over it. The United States is kind of behind the times when thinking about death. You have all these other cultures that believe that your soul moves on through the world after the body is gone, or that you put the body in front of the house so that it guards the family, or that you exhume the body so that it can help you understand stuff about the world you are living in. We [as Americans] have a deep fear of death, and dying, and the dead. We don’t make peace with it. In Another Brooklyn, August’s whole journey is to make peace with death.

How do you grapple with loss and death?

It’s hard. I feel like I’ve had a lot in my life and in the last couple of years. I don’t believe people who die leave us. I think they’re very much with us and here to guide us through our own journey to the next place. That does help me a lot, I’m much less fearful of death. I still don’t want to see a dead person’s body but I do feel like my mom’s with me, I feel like my editor’s daughter is with me, I feel like my uncles and all these people are still with me in this way. That gives me so much peace. I feel kind of sad for people that can’t see that, who have this feeling of being lost—thinking this is all there is, just a human body in the world.

Another Brooklyn Is Available Now. Check out Jacqueline Woodson’s official website

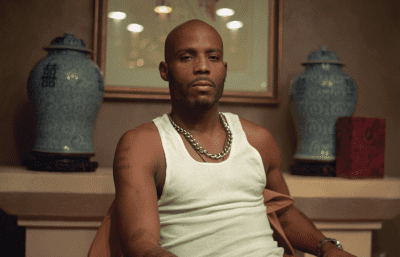

Photos by Jane Bruce

You might also like