Coney Island Baby Brings the Heat

Come Sunday, the boxing world will tune into NBC at 5 o’clock to assess whether a former Olympian—Errol Spence Jr.—lives up to his professional, Pierce-ian billing: “The Truth.” He’s undefeated since the London games, fighting fluidly and with power, a welterweight with all the right attributes who’ll likely win a title within a year (he could win one now, probably).

But Spence is from Dallas, and these fights are the first in the new Ford Amphitheater on Coney Island, the urban pleasure park depicted in countless New York lives (Think: Woody Allen’s house under the Thunderbolt; Buster Keaton and Fatty Arbuckle romping through the public bathhouse in a 1917 silent classic; Saoirse Ronan opening herself up to the world in a green “bathing costume” in last year’s Oscar nominated Brooklyn).

In another year, perhaps, boxing would’ve snubbed its nose at all that parochial pride and collective memory and held further events at casinos. But every few weeks this summer, boxing has returned to Brooklyn like the ghost of Campy and Hodges, Jackie and the Duke. You can’t shake it—like some kind of otherworldly middle finger to the specter of Robert Moses (though it’s really the doing of boxing impresario Al Haymon, who mysteriously confines himself to his Las Vegas headquarters).

In June, 13,000 packed the Barclays Center to see a tense welterweight championship. In July, 9,000 saw perhaps the fight of the year, the featherweight showdown between Mexican-American champ Leo Santa Cruz and upset winner Carl Frampton (whose legion of singing Gaelic fans poured onto the streets like burbling Guinness).

I don’t know what Brooklyn was like in the radio days of Red Barber, but we must’ve been close. And I’m sure that came through in the broadcast—but only in part. Because besides the champs and challengers and fierce crowds, there were hometown girls who fought on those cards but weren’t televised (no, women didn’t fight in the cigars-and-sepia era, but it’s the spirit of the thing).

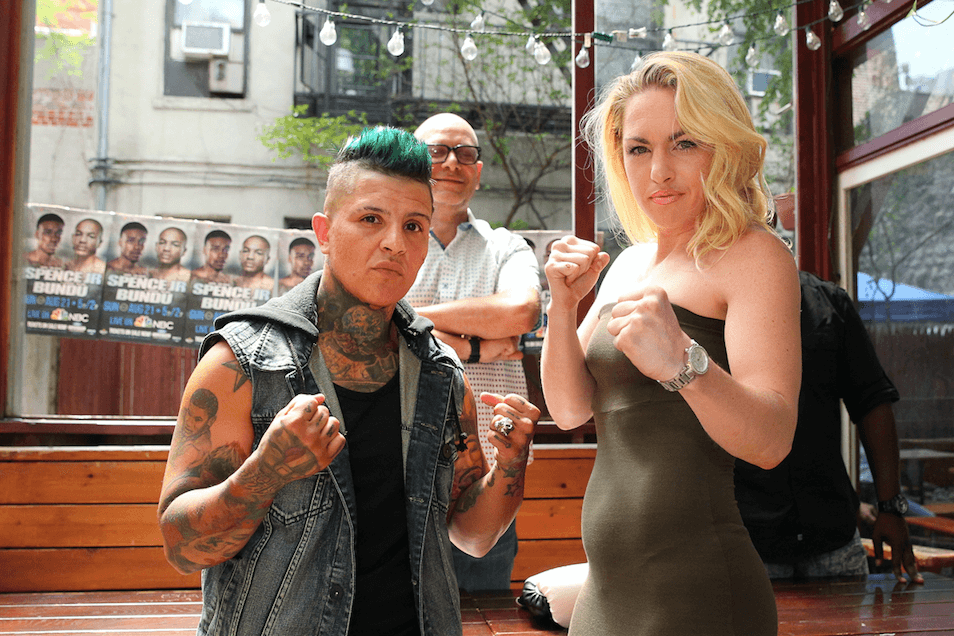

Last time, the boxer was Amanda “The Real Deal” Serrano. A quick, slick, southpaw, she KO’d her opponent in one round. Which wasn’t a surprise: She’s the top-rated female featherweight in the world. And a Bushwick High grad.

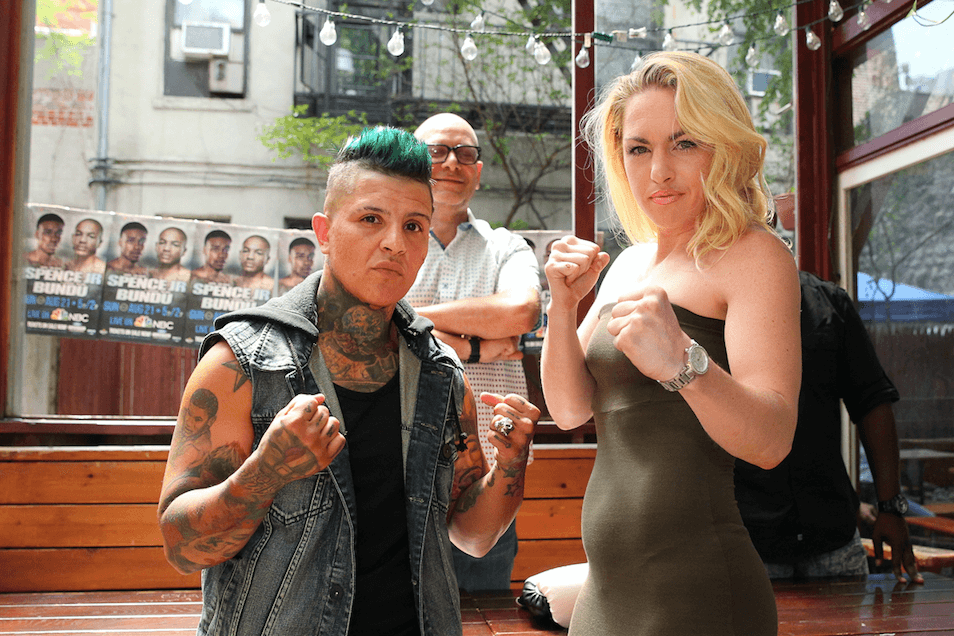

In June, Heather “The Heat” Hardy added a 17th win to her record. She’s the sixth-ranked female featherweight and a Gerritsen Beach native (the seventh-ranked woman is from Brooklyn, too, but I can only fit in so much).

Now, Hardy’s back, slotted onto the Coney Island card by her promoter Lou DiBella, whom she won over by selling tickets to the people, literally (trainer “Blimp” Parsley guaranteed DiBella that this girl would sell $10,000 of tickets, and Hardy went to Times Square, set up a stand and made it happen).

She still works it. She was hyping her latest match on Fox 5 this past Sunday night, and it’ll air on-delay (during the Olympics, that’s pretty much as good as live) this upcoming Sunday night, at 9, on NBCSN. That’s Hardy’s way; she has an overwhelming drive. It’s equal parts tenderness and grit, and she knows how and when to show it.

She’s also a single mom with a 12-year-old girl named Annie (whose name’s musical evocations of “Tomorrow” are fitting). When Heather was Annie’s age, she was raped. Years later, her now-ex-husband took her money. She lived out of a car at one point, a la Kimbo Slice.

So many boxers experience pain and privation. Often, that’s how they stumble into boxing in the first place: it’s a last resort or an escape from the streets. But that’s not really Hardy’s narrative at all. She makes a point of saying she grew up poor not to emphasize her own rise but to underline how easily other girls might be able to do the same. She’s invited to speak to lots of summer camps.

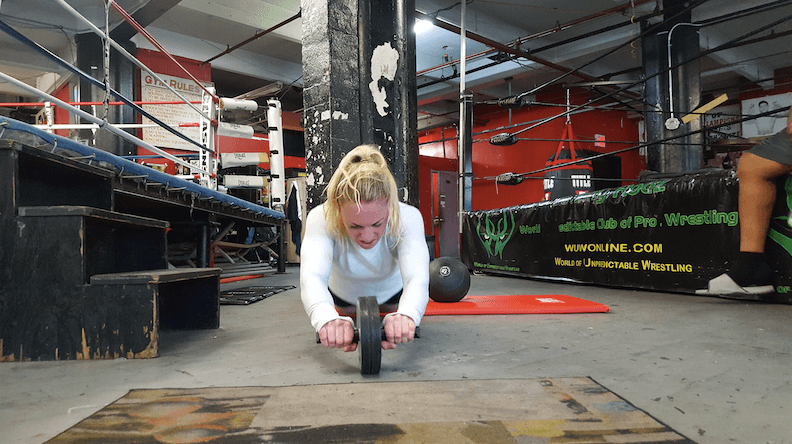

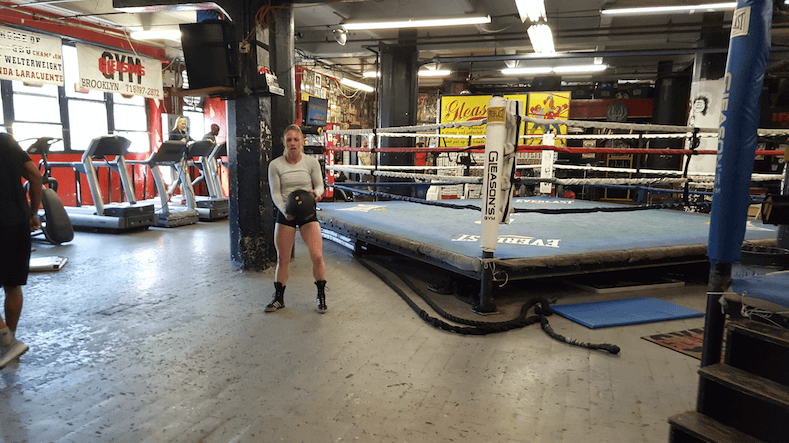

Before boxing, Hardy knew karate. Then on three weeks’ notice, in her 20s, she took a match as a kickboxer. “For the first time in my life, I felt like I was good at something,” she says, in her office at Gleason’s Gym in Dumbo, after a grueling fitness session involving medicine balls with handles, battle ropes, three different types of pushups, and lunges onto the ring apron (that was her second session of the day; the first consisted of technical boxing moves).

Hardy already had a degree in forensic psychology from John Jay and a job with a furniture company when she took the kickboxing match. Incidentally, you know someone’s tough when on almost no notice, they say, Yes, let me try this combat sport involving kicking and boxing.

“For whatever reason, having that first fight really fulfilled me,” Hardy adds, as she downs a recovery shake the color of Pepto-Bismol.

Hardy set out to learn boxing in the amateurs, winning the New York City Golden Gloves and a national title along the way. She turned pro almost exactly four years ago, just as the Olympics was holding its very first female boxing competition in London. Training alongside girls who had spent their lives in the amateurs, she saw the feelings of vindication and relief on their faces, the spirit of a collective victory.

Now she’s 34 years old and the sport’s so much a part of her life that her teenage daughter dismisses it like any other kid would her mom’s profession. In fact, Heather would love Annie to join her and train, just so they could talk about it together. Up until this fragile point of puberty, her daughter has been more like a sister to Hardy. And she wants to keep it that way.

Meanwhile, it’s not as though Annie’s friends would ever know Hardy boxes by her appearance. Yes, she’s suffered two broken noses and a gash requiring 20 stitches, but you can’t really tell. There’s a thin, white line on her forehead and a slight indentation on her nose that seems like a natural feature (my dad’s broken nose, the result of an unfortunate Superball accident, is far more pronounced).

As for the sport, women are once again boxing in the Olympics, though in fewer classes than the men—a point which has been noted by both The Wall Street Journal and The New York Times, thanks in part to Flint, Michigan, native Claressa Shields, a 21-year-old who won a gold in London and doesn’t back down when it comes to her sport receiving its due.

Hardy shares the same spirit, wishing female boxers were as publicized as UFC’s women, especially since she believes there’s great depth in boxing, tons of women hitting bags across the country whom we should know (she has high praise for Dana White taking a chance on Rousey back when). And yet, she maintains a characteristic balance and modesty even while making the point that all it takes is one good women’s fight snuck between two men’s fights on a televised card for the women to break out. That’s how it went down with Rousey. But, Hardy adds, “It’s really easy for me to say what to do.”

She appreciates the craft of Mayweather but not the man—the same with any malfeasant but talented boxer. Someone once asked her whether she’d punch somebody on the street. Of course not, she said; you don’t see firefighters going around picking up and spraying peoples’ hoses, do you? It’s called a job.

We giggle and mime the scene.

“There’s no fire!” I say. “Stop spraying!”

“Shut up!” she roars. “This is what I do.”

**********

Hardy gives boxing lessons to supplement her purses. Anyone can train with her, and I’d recommend it for her unique eloquence alone, forget about the punches. She recently was going to accept a kickboxing match as a side gig, but then DiBella called with the Coney Island offer.

Hardy’s not a natural. Her footwork isn’t on point, her punches aren’t powerful or particularly quick. She’s faced a bunch of soft touches on her way up. There are likely many better boxers who receive less attention because they don’t live in a big city.

But Heather does live in a big city, and it’s ours. And, lacking a real amateur background, she busts her ass each sweltering day to improve as a pro. On the feet and the angles and the power. I’m gonna root for her until she faces one of her fellow borough girls. They all support each other while imagining what it’d be like to top the others (it’s like the Olympic gymnastics team in that way).

Then, if Hardy and Serrano go at it, or Alicia Ashley comes to play (top 122-pounder and Hardy’s trainer’s sister), I’ll be content to root for the event alone—and the dwellers of this naked city who’ve united once again on a Brooklyn beach to watch.

You might also like