Talking to the Woman Behind New York Magazine’s Ask Polly Column, Author Heather Havrilesky

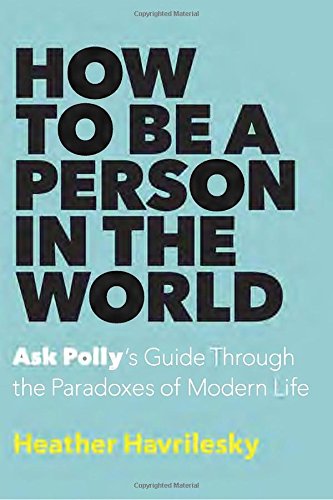

It’s unsurprising that Heather Havrilesky, aka New York magazine’s “Ask Polly,” is really, really easy to talk to. The advice columnist (and memoirist, Bookforum book critic, long-time Salon tv critic, and once and future comic writer) has made her name (or rather Polly’s) on her intense, often mesmerizing, anecdote and fuck-filled responses to letter writers asking for help, mostly existential, with their lives. Havrilesky’s second book and first collection of “Ask Polly” columns, How to Be a Person in the World, is the work of a professional writer who sometimes gives advice, rather a professional advisor who sometimes writes. In this way Havrilesky and “Ask Polly” share kinship with other writers-turned-advice gurus: Cheryl Strayed’s “Dear Sugar,” Mallory Ortberg’s “Dear Prudence.” The advice they give is not the kind that Emily Post or Dear Abby would dole out, but neither do they receive the same kinds of questions: Strayed has memorably been asked “WTF?”; Havrilesky, “Are you sure?” Both offer answers that mix memoir and essay and direct address. “We will always be unsure,” Havrilesky writes in response. “There is still hope for us. We might just make something beautiful, some day. We might just surprise ourselves. I choose to believe that. I choose to believe it, every single day.”

I talked to Havrilesky a lot about gender—the particular burdens (and privileges) of being a young, educated, not-in-abject-poverty woman come up again and again in her columns—as well as making space for yourself and feeling feelings and growing. I could have listened to her all day.

Advice columns are so frequently gendered female, both in terms of readership and in terms of the intellectual and emotional labor of the writing itself. (Whereas, for instance, Tony Robbins’ brand of advice is coded so aggressively male.) Do you have a sense of the gender breakdown of your readers and letter writers?

I can’t really tell. I definitely think there are more women than men reading the column, but I’m assured by my higher ups at New York that The Cut has almost equal female and male readers. I was thinking I should do a man week at “Ask Polly” and just answer letters from men every day for a full week. There’s kind of an assumption in our culture that men have less complicated issues to discuss—that’s not the case at all. Even if the issues present themselves through the filter of male language, sometimes it’s more exciting to address a problem like that. You can open up the possibility that there are all these complex kind of needs and beliefs and desires that aren’t necessarily expressed in the culture for men. I love trying to get people in general to honor the complexity of their thoughts and desires and true wishes and frustrations. I think men in particular encounter the short end of that stick over and over again. We tell a story about men, how they only want sex and power, how they don’t have more subtle needs for validation than that. It’s not true. But advice columns aren’t the first place a man would look to figure out what’s going on with him.

Do you see a difference in the kinds of questions you get from men and women letter writers?

The questions I get from men tend generally to focus on how do I solve this problem. “I’m looking for a concrete answer. You seem smart. I need a specific directive on how to handle this situation.” That’s one kind of letter from a man. I do get letters from men that are more like, “I’m depressed. Things are bad and I don’t know how to make them better.” Sometimes I’ll get letters that say, “I don’t how to crack the code of how people interact with each other. I feel like I’m out of step with social cues and I don’t know how I need to be to get people to like me.” Those are kind of heartbreaking because you want to say, “It’s easy!”

What do you say to them?

Just to pay attention to what people are talking about, to respond and ask questions. The one reoccurring letter I get from men is “What am I supposed to say to that?” You kind of want to say to them, “You’re not a robot! The things that are coming at you are not as complex as you think they are. What is the heart of the desire that’s coming at you?” I think men feel they have to somehow match the language that a woman uses in order to engage in a conversation. Obviously that’s not the case. It’s a matter of keeping it simple and asking questions: How do you feel? How does that affect you?

For both men and women, it’s easy to feel like you have to be prepared to go out into the world and be acceptable. The people we hear talking in our lives, in the media, in interviews, on tv, in the world, seem to know exactly what they’re about to say, because they are comfortable. The conversations we overhear and the conversations that are blasted at us tend to be either comfortable conversations, people opening up to people they trust, or crafted conversations by seemingly careful, erudite, well-spoken, eloquent human beings holding forth on various subjects at a rapid clip with great intelligence. Or we read tweets that are 140 well-chosen characters. And so we tend to feel like we have to be prepared, that there must be a cheat sheet. People forget that they can just slow down and be, that they can just take up space and not make a sound. It’s not that hard to be accepted, even just by walking around asking questions. You don’t have to have a song and dance just to exist.

How did you yourself come to that understanding?

My parents were a little out of step with the mainstream. I grew up in Durham, North Carolina. It’s a liberal town—it’s not the horror show Southern town of your gothic nightmare. My parents were from Illinois and Pennsylvania respectively, they were kind of misplaced midwesterners and northerners. They grew up in interesting, wild, dysfunctional families. My dad was an academic too, and they’re kind of weirdos. You don’t learn social skills being an academic’s kid.

I remember going to a country club in eastern North Carolina with my boyfriend, who was a southern guy, when I was a freshman in college. This older woman was standing at the entrance and she said [here Havrilesky affects a pretty convincing accent], “Hi, I’m Sheila McCombs, welcome,” and she shook my hand. I just said, “Thank you.” I didn’t even know that I was supposed to introduce myself, which sounds absurd. I did not know the basic polite patterns of human interaction. And college is its own specific thing; you’re chugging and high fiving. Everyone I met in college too—I went to Duke—they had a sort of northeastern, very polished, upper middle class vibe. The whole way of being southern in the seventies in Durham was not my way.

When I got out into the workforce, I did not understand how to interact with people. It was as if I was on the spectrum. I felt like I needed a little cheat sheet in my pocket. I didn’t realize that once you got past, “Hi, how are you,” thanking and greeting, that shutting up is the rest of it. You think you are not supposed to shut up—when you are young you think you have to prove that you’re worth something. Now I end up saying, “Listen. Just listen.” That’s 90 percent of the battle. Try to be comfortable enough with the silence. Think more about other people’s needs—not in a subservient way. I think a lot of people just want to blend in, and the best way to blend in is hold your own space, cultivate a comfort with silence, and ask people questions—real questions—about what they’re talking about, instead of feeling like you need to be a witty banter machine.

We talked about the kinds of questions you often get from men, but do you see any patterns in the questions you get from women?

Women often ask, “How do I fix this relationship to make it work?” Usually if you are asking how to fix it the answer is you can’t, you need to take it to the junkyard and move on. There are a lot of questions about “How do I control reality to make it to my liking?” Women learn to calibrate themselves for public consumption, to make fine-tuned changes to themselves in order to be more admired by some kind of male gaze or just by friends. They’re just much more in tune with “how do I get people to like me?” and once they get people to like them, they think they can apply the same rules to love. “How do I get him to love me more?” “How do I get him to stop acting this or that way?” “How do I change the situation so that it works?” The answer to that, nine times out of ten, is you can’t. Or—if you let go of your preconceptions of what it needs to be and see what it is—you might find you are attracted to problematic men and problematic situations. Really what you should ask yourself is if you feel happy in your situation, or if you need to get out. Start opening your eyes to people who are actually looking straight at you as opposed to distracted, those who really are just in for the chase and not much else afterward.

That’s kind of an oversimplification, honestly. The lion’s share of letters I get from women now are about believing in themselves, asking for more help when they don’t know how they’re going to get the things they want. A lot of times that involves career or moving to a new city and not knowing anyone. In fact friendship and career are the two big things I grapple with right now. We tell each other that these things work out and it’s all fine, but the emotional journey to having a job you like and having friends you can count on is so grueling. I feel a little guilty for putting it in those terms because the world is so messed up and so many people don’t have the chance to drink clean water, for example, or survive in a country where they’re not oppressed. But I do think we underestimate how traumatic it is for young women to land in a new city and be expected to build everything from scratch.

What’s the core message you are trying to get across in the advice you give?

The thing that kept coming up again and again in the very beginning was: before you ask for acceptance and love from other people, you have to accept yourself. That includes accepting your so-called negative traits and the so-called negative emotions that you seem to stumble into day in and day out. Accepting your flaws and even embracing your flaws was the very heart of what I was writing for the Awl in 2012. I was so stuck on that because, until I personally decided that the way that I am is going to have to fucking be okay, it wasn’t working to either mask my flaws or pretend they aren’t a big deal or that they don’t come up every fucking day. I had to accept that I’m kind of an angry person, I’m kind of a moody person.

Why was that important to you?

My mom used to call me fault-finding when I was younger. It really made me mad, because she is too. But, you know, I am fault-finding. I’m sensitive, yes, but I also enjoy picking apart—not just flaws but what they’re made of—what motivates people. It’s not malicious—I just want to understand the full story. The fact is most people are not that centered and balanced and relaxed in the world. You meet people and you can think, “This person has their shit together. She is incredibly charismatic. We are interacting enjoyably in other ways.” But then you pick up that, “There’s something coming at me. There’s something that’s not computing. Why does she sound like a robot when she talks about her relationship? Why does she start to get prickly when I start to talk about my career?” People on a daily basis in mundane ways try to dominate each other in conversation.

To generalize, women notice a lot about what’s happening around them psycho-socially because we are raised, basically, as subordinates, whether we know it or not. The culture treats us as subordinates whether we’re consciously aware that we’re being treated that way or not. There’s this book, Toward a New Psychology of Women by Jean Baker Miller, that’s all about this. When you’re a subordinate, you notice a lot about the world around you, you know a lot about the people who have more power than you. It’s only adaptive to do so. But when you’re really smart and sensitive and you look around and see all these weird dynamics, you want to get to the bottom of that. Women are often really good storytellers because we’re taking in so much information about people’s motivations, but we’re also a little paranoid sometimes because we have been dominated by a lot of people. One side of us worries about being dominated, and another side wants to dominate people—in part because we’ve been subordinated for so long.

How does this manifest itself in your life?

One story we tend to tell about ourselves is, “Ugh, why do I just want to talk shit?” I don’t want to go out on a limb and say I give everyone permission to talk shit. I myself have talked too much shit at times and also been paranoid about talking shit at all. But I almost have a perverse attraction to shit talking when I know it’s inappropriate. It’s a way of letting off stress. It’s a way of being intimate with people, when you can trust them enough to say, “Everyone’s fucking crazy”. It’s not like you are saying “Oh these people are bad,” you just want to get to the bottom of why people take on these behaviors. I feel like I walk through the world all the time saying, “Oh my god what am I seeing?” I don’t want to be a judger—I don’t want to be dominated by my thoughts about people. I would much rather be led by what I feel about them. That’s been the long road I’m on. If you feel uncomfortable and weird and self-conscious around someone, interrogate all the reasons for that as long as you what. But eventually you have to say, “Gee, I might just decide not to be around this person, because there are other people I feel so good around.” Maybe even inexplicably. You have to accept that you do the fucking things you do. And that’s a radical act! It’s a radical act to say, “I don’t have to feel bad about the way my mind works. I don’t have to feel ashamed of being smart as shit.”

Women feel a lot of shame about being really smart. I think women are so often really brilliant human beings, partially because we’re tuned into the things happening around us. And that’s a hugely gendered, sweeping statement—not every woman alive is the smartest person in the room. And I’m not even fetishizing intelligence. I’m just saying, as women, our knee jerk reaction—having marinated in this culture for years—is “I need to fix these things. I can do it. I need to tamp down my talents and figure out a way to be more like this male-dominated world around me. Everything that’s an aberration from that path is me fucking up.” When you tell yourself stories like that, what you are telling yourself is “All my brilliance is shitty and I need to be stupider.” The flip side of that is, when you meet someone healthy and they’re not buzzing and thrumming and making noise and creating problems, it’s an acquired thing to be able, if you are smart and you are a noisy mess, to look at this person and say “They aren’t stupid and they’re not being inauthentic. This person is just really healthy.” Making room for people like that is just as big a challenge as making room for your own madness and brilliance, which are, you know, mostly related. As defined by our cultures these two things are one and the same.

That’s the goal of the column, really, to find myself in a good place where I’m like, “Oh this is a good theory. I’ve never thought about it quite this way.” To me that’s what a lot of women need—women need to run long. I think about the noise and colors and magic inside of us that we can’t even access because everyone’s like, “Get to the fucking point man. Why are you making it so complicated?”

If you want complicated answers, I’ve got them. And I think there are places to go from there—why accept your flaws? How does it unlock the gates to good things?

So, how does it unlock the gates to good things?

The chronology of “Ask Polly” is probably this: accept your flaws; accept others’ flaws in order to have relationships with fellow flawed human beings; embrace your flaws because they hold the key to what you potentially can be. That’s what I want to write about in another book, looking at the things you won’t let yourself do, looking at the things that embarrass you the most, looking at the things you’re supposedly shitty at, looking at the things that make people mad about you. If you lean into those things enough you will uncover your truest desires as a human being. (I’m not talking about I like kicking little animals. Obviously that is not included in the picture.) One example might go, “This kind of person frustrates me because she’s always showing off. She talks too much. I don’t like it.” Eventually you get to, “I value not talking,” to “I used to be a show off and everyone told me to shut up” to “I just learned to shut the fuck up all the time’ to “actually I always wanted to be a comedian” to “my mom told me I was annoying and obnoxious” to “I never got to do comedy, goddamn it.” People who let themselves do things that you will not allow yourself to do will sometimes become the biggest, most chafing, irritating people in our lives. What you discover when you look closely is “Holy shit the things I’ve been telling myself I would never ever do because I don’t want to be that person are actually the things that I want to do the most.”

Have you had personal experience with that?

I’ve always said “Whatever, fashion, who gives a shit.” I want to be comfortable. I don’t believe in walking around in uncomfortable shoes, putting on makeup for no reason. Screw all that stuff, that’s catering to the patriarchy. Not like I condemn people who look that way, I look at people who look that way and say, “Goddamn it, how did she do that.” Secretly or not so secretly thinking, “Oh my god you look so good today. How do you just put a little time in and look so good? I wish I could look good.” What I’ve learned recently is, oh, I really value beauty. Which, whatever. Maybe I actually want to be someone who dresses nicely even when I’m not going anywhere? Because I’ve been working from home for 20 years, it seems like a lot of effort. But on the other hand, once you know how to do the basic things—like, there’s this new kind of so-called tinted moisturizer that’s actually a magical form of foundation. It doesn’t look shitty on your face! Who fucking knew. Once you start asking people questions—like “How is it possible that your hair looks so good? How many millions of things do you have to do to make your hair look that good?” “Oh, I just get these keratin treatments and then I put this product in.” “Holy shit, really?” I thought, that’s nothing! I could have hair that looks good? That would be kind of convenient, to not have a frizzy head of a disgusting insane frizz hair, which has replaced my ample shining hair I had when I was younger. That would be great. I’ve been asking myself: Have I valued personal appearance all along? And by not reacting to it, have I been bitter and nasty about it? Have I been punishing myself for never indulging in it all these years? Especially when I could just decide: “Hey I want to look good.” When I was younger I just didn’t want the attention that came with being bugged on the street, though it’s not like I was some kind of ravishing goddess. Still some part of me felt like if I let myself do all the things I wanted to do, I would take up too much space and be a little too fabulous for the world to tolerate. Because I didn’t tolerate women who were talented and beautiful and smart, so why the fuck would I think that I should make that kind of space for myself?

The final piece of I didn’t figure out for a few years of even writing” Ask Polly” is how to feel your feelings. How do you get to a place where you feel in touch with your feelings. That is the hardest. It’s just deciding that it’s okay to be angry sometimes, that you can allow yourself anger without beating yourself up about it. It’s okay to cry a lot. When I’m crying a lot it means I’m in the right place. I feel much happier since I learned to just wear my emotions on my sleeve. It’s not like I’m flying into a rage all the time now that I feel my feelings, I actually don’t. I’m not as temperamental, paradoxically. I get letters from people who are clearly intellectualizing everything single thing in their lives. They’re trying to solve these mind puzzles. They just need to put down the puzzle and feel their way through the dark in order to figure out how they truly want to live.

Has writing advice changed you?

I feel like I have to be experimenting with living in really good new ways. If things in my life feel a little bit broken, I have to look at them really closely and try something new. I think one of the qualities of the column is me saying, “Here’s how you need to be. You need to try to do this or that, and that might really solve this problem.” So I also have to ask myself, “Well, are you doing these things?” If the answer is no, I end up carrying that around it with me. It doesn’t feel like a punishing thing, though in the beginning I probably did. One of the things I was carrying around initially was I didn’t feel like I was feeling my feelings enough. I didn’t feel happy, and I needed to figure out how to feel happy. Now I do feel my feelings and I do feel happy. I feel very happy. It’s crazy. I was not an incredibly happy feely open person when I started writing this column and now I am.

Two years into writing the colum, I encountered this person online who was typical kind of intellectual, young, kind-of-not-into touchy feely things. I stumbled on some comment she wrote that was like, “Oh, whatever I am so sick of this fucking ‘Ask Polly.’ Everyone thinks it’s so great. I hate shit like that.” I remembered feeling that way and I understood that. I used to hate things that were—just advice from grandiose touchy feely people, Jesus. You can go fuck yourself. I kind of evolved enough to forgive people for disliking me. A former version of myself would like me that much either. That feels good. It’s good to forgive the world not for liking your shit that much. But I’m not perfectly that way every second of every day. It’s not like I don’t get stung by bad reviews or nasty comments.

My writing used to be pretty rambling—I complicated things I didn’t need to complicate in an effort to address the whole picture. My column is a little more like an essay that it used to be. It’s not always the most literary in the world, but I try to hold myself to a high standard. I really want each column to be better than the one that came before. Obviously I can’t pull that off consistently. There are weeks where, even though it doesn’t represent the apex of my achievement, it’s nice to write about Yes the band for several pages or Kanye or something that’s happening in the news as a metaphor for a person’s problems. I just love writing the column. It’s the purest writing I’ve ever done. It’s the free-est writing I’ve ever done.

I do still find myself cowed by problems—I just don’t experience them as such big fucking deals the way I used to. I used to define myself by asking “Why can’t I handle life? Why can’t I get my shit together?” Now I’m in a place where I say, “Give me more challenges.” I want to have adventures. I’m going to talk to people that make me uncomfortable. I’m going to show up for weird meetings. I’m up for that shit. It brings out my insecurities but it makes me tougher and more able take on things that might really open up my life. I’m all about failing right now. Do things you’re shitty at.

Like, I’m writing all these cartoons for people. I said if you’d buy my book I’d draw you a cartoon. I owe 30 cartoons. They’re bad cartoons. But I’m going to get better probably after I do 30 of them.

You might also like