Paging Gertrude Stein: Inside a South Williamsburg Writing Salon

On Sunday night, just before a downpour washed New York City momentarily clean, I rode an elevator to the 8th floor of a residential building in South Williamsburg. A sticky note on a door at the end of the hall read “Writers Salon” and instructed me to hit the black doorbell beneath it.

Shortly thereafter, I was greeted by Georgia Clark, a novelist and Australian native, who recently sold her third book, The Regulars, to Emily Bestler Books, a small imprint of Atria, in turn an imprint of Simon & Schuster. Behind Clark, and beyond a large panel of new windows, gray clouds hung above the Williamsburg Bridge, and Manhattan lay in the distance. Moments later, the sky unleashed itself.

Inside, Clark was shoeless and wore a summery dress; she gave me the natural instructions of a gifted hostess: I could leave my shoes at the door; come to the kitchen—would I like a glass of wine? I don’t love white, but the chilled minerality of the liquid she offered was outstanding. Clutching our stemmed glassware, we transferred to the seating area in the living room before the other salon members arrived. Clark’s girlfriend stayed in the kitchen preparing a giant bowl of guacamole to add to the spread of cheese, olives, grapes, and hummus already arranged in front of us. Quiet jazz played at the right conversational volume near the entrance.

“I was always a freelance writer after I finished uni,” Clark tells me, her feet curled up beside her on the couch. “I wanted to be a film director and I spent a lot of money making really bad films—you have to blow all of your money on something nobody ever sees,” she recounted of her post-college professional life. It was a depressing thought, but she said it with the confidence of someone who no longer primarily fails. “That’s just the life of an artist: piss money off the walls until you learn how to make it back.”

Soon, Clark discovered another way of telling stories that did not involve wasting prodigal sums of money: writing novels. She wrote her first and got addicted to the long-term challenge of it. “It was so hard I wanted to do it again and better; no one runs one marathon,” she said. I told her I’ve never written fiction. “When you’re writing a book, you’re in whatever world you choose, and it’s intoxicating, because you bring fictional worlds to life, you invent people and exercise your demons.” Before I could ask about her particular demons, she filled in the blank. “Like, I’ve literally killed people I didn’t like in stories, because you get to do it. You’re sort of playing god, and it’s a high.”

I hadn’t figured out how to take that drug yet, but, what was clear—especially if you’re digging into those kinds of places—is that novel writing has to be done alone. And given that, it’s important to create a community around you, said Clark. “You want to be accountable to someone, especially before you get an agent.” Without external touchstones, the internal struggle of the novelist is very real. “You become aware of your own limitations and frustrations and inspirations—it’s a lot about being able to manage your own mental health.” Voices will creep up, she said, that tell you you won’t succeed. “You kind of basically have to ignore that voice in your head, and tell it to fuck off.”

Previously, I had been under the impression that the aim of a gathering of writers was to aid each other’s writing. In a sense, that was true of this salon, but not in the traditional way I imagined, not necessarily in line with my fantasy of Gertrude Stein’s Parisian salon. “It’s different,” said Clark, of the gatherings she held the first Sunday of each month. “The purpose of the salon is social.” The doorbell rang again, and she got up to greet more guests.

**********

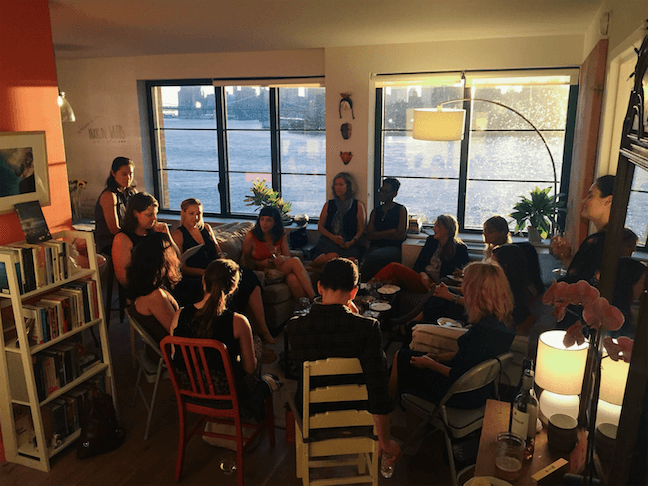

Ultimately, around 15 writers showed. We squeezed ourselves around the centerpiece of abundant snacks, installed in soft armchairs, sofas and stools. There was a lot of energy, maybe the product of a group of people who are accustomed to being alone most of the time: this was not just company, this was sympathetic company. Clark made sure everyone’s glasses were “charged” before people took turns introducing themselves and their work.

A middle school English and History teacher Brian Platzer had sold his novel about race riots in Bed-Stuy to Atria, the same Simon & Schuster imprint that bought The Regulars; a YA novelist Marina Budhos was in the middle of planning her own book tour for a “crossover novel” about an 18-year-old Muslim boy who is spied on, gets in trouble, then becomes an informant; another woman, Becca Schuh, had just cut back waiting tables to part time, because, finally, she had more writing work, which “feels like a very big achievement,” she announced. Next, Michelle Manning had also cut back her office job to part time. Four days a week she worked at completing her second YA novel. “I’m calling it a sequel, but I’m just trying to get an extra sale out of that,” she said, and laughed affably. After that there was a coming of age novel centered around a big Mormon family—though the author, Charity Shumway, had suffered the disappointment of not getting the editor she wanted. “Maybe it’s good!” she coached herself, repeating a spiel Clark had given earlier: in publishing—if you’re a writer working with a publishing house—no news is bad. The goal is: Keep your writer happy.

It was instructive to hear the depth and breadth of these histories. Working alone, it’s easy to be grossly unaware of anyone else’s journey. If you haven’t gotten to where someone else currently is, their progress makes success feel a little more attainable. For a mentally unstable writer—and I say that only as a partial joke—those stories are real beacons of hope. Any jealousy aside, it is nice to know that, if you take on the ridiculous task of writing a novel, the system can work. Books deals, whether puny or grand, still get made.

Georgia gave us a little background about herself—how this, her third book, had been sold to Atria—and how the salon began. “So much about writing is solitary, and it’s so important to just find ideas from each other, see what works and what doesn’t work, find connections and share successes,” she told us. And then she told us we’d have a reading from Jess Rowland.

**********

In addition to having compiled a collection of short stories called The Disasters, Rowland worked in a science lab and composed music. “I should say I just sent this to the press that will publish this in California,” she told us, clutching the paper with a selection of her manuscript. “That said, I love feedback.” She sat on a stool and almost began, then offered a qualifier. “If you hear something that doesn’t make any sense at all, it’s not you—there wasn’t something in the deviled eggs… or maybe there was,” she joked. But in essence, she summarized, “It’s weird.”

Rowland’s selection from The Disasters was about an implied volcanic eruption. It combined science fiction and absurdity, and two characters who worked in a department of Volcanology, which happened to be located in the Institute for Advanced Toothpaste Research, across from a Lacrosse stadium at a university in Kansas. It was funny; it was nuanced; it was dry; it was rich, and so good.

Afterward I told Rowland it reminded me of Kurt Vonnegut, and she revealed he was a huge influence. But it was not like listening to her was exactly like listening to Vonnegut; it was just that Rowland had tapped into something that clearly worked very well for both of them. Slowly, then more readily, people shared the bits they liked, and asked questions about the writing. A small press in California would publish the collection in August. Rowland said they published stuff form the late 60s with San Francisco poets and progressive writing. Her friends ran it, and, according to Rowland, told her The Disasters was “a little different, but yeah, we’ll take it,” but I had a hard time believing this. The writing was fresh and smart and, yes, weird, but I cold not wait to read more.

Someone asked how much research she had done for it. It had a such a clearly, scientifically correct foundation. “There wasn’t any research,” Rowland said with a laugh. “It’s mostly made up.”

**********

The official program was over, and the rest of the night was for more casual talk. Clark filled up everyone’s glasses again and we attacked the rest of the guacamole and olives. Clark shared how, despite the fact that she had sold her book and was working with a publishing house, she’d also hired freelance publicist. “A woman named Crystal Patriarche,” in fact, said Clark. Publishing houses, like people, can only take on so much.

Furthermore, she offered, you can always hire interns. “If you’re a published author, and you have a book, you are interesting to college students,” she said matter of factly. “I offer mentorships and I have had interns on and off for years.” For example, one is at work finding 20 podcasts that mention authors. “There is an endless amount of publicity that needs to happen,” she said. “When I came [to the US], I was like, interns have jobs that I got paid $50 thousand dollars for in Australia!” we all laughed with a strong foundation of sadness. “I’ve got a bunch,” she revealed; she found them on craigslist.

This was not my imagined glamor of Gertrude Stein’s salon. This was the reality of a roomful of writers in South Williamsburg in 2016. Alone, it was a little sad; at least discouraging. Together, it was funny and helpful. Writing days might be solitary, but, ultimately, wine and struggle are best when shared.

The Regulars is out 8/2. Lead image by Lindsay Ratowsky

You might also like