TV Comedies Are So Much Funnier than Movies Right Now, Right?

We are living in a golden age of television, or so I am told at regular intervals that have nonetheless failed to convince me to watch Game of Thrones. I tend to resist this TV-is-better-than-the-movies narrative on a number of levels, the most polite of which is that you can’t really pick a “superior” medium between the two, any more than you can say that novels are so much better than oil paintings these days. More personally, I’m more of a movie guy; I watch TV, for the most part, to relax. I watch movies to engage. But I admit I have been susceptible to television’s charms in one particular area, and that is comedy. Over on the ol’ TV, I watch Girls, Silicon Valley, Veep, The Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt, New Girl, The Last Man on Earth, The Simpsons, Bob’s Burgers, Brooklyn Nine-Nine, Broad City, You’re the Worst, Master of None, and Inside Amy Schumer, among others, at least semi-regularly, and there are plenty more I’m interested in trying.

I go to movie comedies, too—all the time, in fact—but I admit that I haven’t seen many great ones lately, unless you count stuff by the Coen Brothers or Wes Anderson, or indie high-wire acts like Welcome to Me. In terms of broad mainstream comedies, pretty good stuff like Spy or The Boss is pretty much a wash with the disappointing likes of Daddy’s Home, Get Hard, Let’s Be Cops, or We’re the Millers (to say nothing of the truly lousy stuff). Seth Rogen has become pretty reliable, but he’s just one man (with an excellent team of producers, co-writers, and co-stars). The laugh metric seems irrefutable: I go see Sisters, starring Tina Fey and Amy Poehler, and do not laugh as often as I do during, say, three or four episodes of Kimmy Schmidt, which Fey writes and producers; 30 Rock, on which she starred, wrote, and produced; or even the gentler Parks and Recreation, Poehler’s sitcom legacy. I go see Keanu, starring Keegan-Michael Key and Jordan Peele, and the movie doesn’t have as many laugh-out-loud bursts of craziness as several episodes of their defunct sketch show Key & Peele. These were not uncommon reactions to either film; they both received mild, respectful, slightly disappointed reviews, quick to point out that the stars in question had all done better.

And yet: Sisters and Keanu are both good comedies, and don’t deserve to have their reputations wrapped up in comparisons to TV shows, no matter how great those shows are. These disappointments—my own included—often fail to reconsider the contextual differences between a film and a TV show. There’s the obvious structural stuff, like the way a sitcom, after five or ten episodes, has established its characters so clearly that it has little need for introductions, exposition, or other scene-setting details that tend to dominate the first half-hour of a stand-alone comedy; or the way that a Key & Peele sketch needs only the laughs it can produce in five or ten-minute bursts, not any further commitment to its characters (as well-etched as some of them are, and as frequently as some of them recur). These aren’t just advantages for TV shows, either; Sisters allows Tina Fey, so closely identified with her Liz Lemon persona, to play a wacky fuck-up character, while Amy Poehler plays someone more shy and reticent than the likes of Leslie Knope. Cast as sisters who are distraught to learn that their parents plan to sell their childhood home, Fey and Poehler have a punchy familiarity that trades on their real-life friendship, as well as the interests of their screenwriter friend Paula Pell, whose sensibility colors the specificity of Sisters, even when it’s failing to be as hilarious as 30 Rock (an area where most things are fated to fail). It’s not a great movie by any means, but it’s doing and saying different things than Fey or Poehler’s various TV shows, and sometimes the jokes-per-minute ratio does go down when you’re telling a story from scratch. When, at the very end of the movie, Poehler and Fey agree that if their parents’ new condo doesn’t smell like their usual Christmas celebration, they’ll flip out and trash the place, the movie is getting at that peculiar sister bond, formed in pettiness and shared history. This doesn’t make Sisters as brilliant as either performer’s best moments, but it does give it a reason for existing.

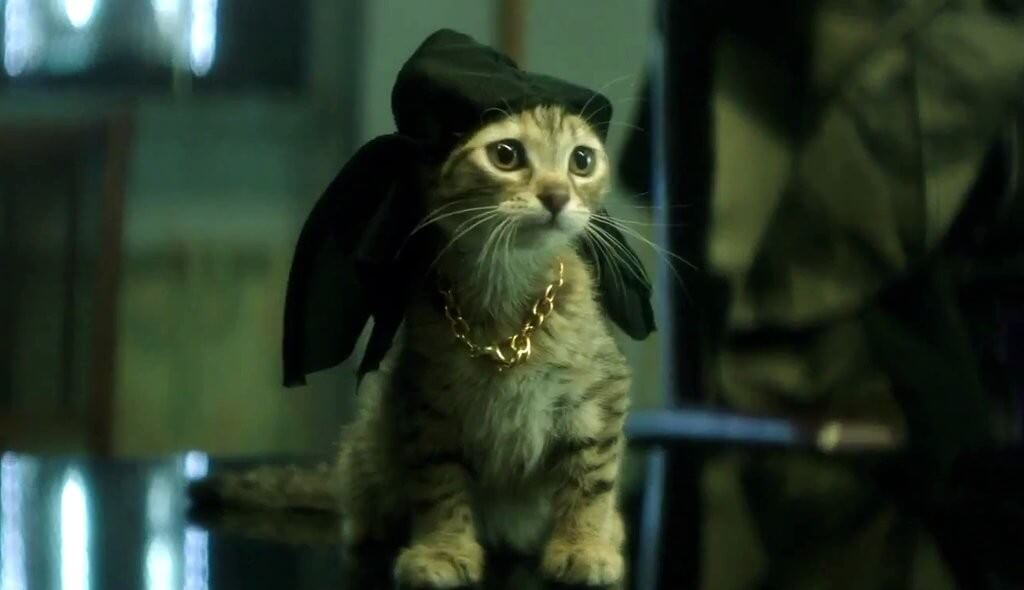

Keanu is even more pointed in developing its buddy dynamic and, in doing so, examining the issue of racial identity. Key and Peele play cousins, both on the nerdier side of things, at very different junctures in their personal lives: Clarence (Key) is a family man who wants only to please his wife and child, while Rell (Peele) has been devastated by a recent break-up. I’m not certain if the kitten who turns up on Rell’s doorstep is called Keanu because he fulfills a function similar to the puppy at the beginning of the recent Reeves actioner John Wick (it seems to be in the Key/Peele wheelhouse, but no explicit reference is made), but in any event, this very tiny, very adorable kitten gives Rell a reason to live—and when the kitten goes missing, a reason to fight. Rell and Clarence embark on an impromptu undercover mission, mistaken for and then posing as fearsome assassins to infiltrate a local gang (the “Blips,” a Blood/Crip team-up) and get their cat back. Rell goads Clarence into it for the sake of his cat, but Clarence finds himself taking to the gangbanger lifestyle, using his team-management skills to improve the Blips’ communication skills.

This is not a Key & Peele sketch. It could have been—any number of bits in it could have been killer five-minute viral sensations—but it’s very clearly a story, however shaggy it gets moment to moment. Clarence finds gleeful freedom in “acting black”—that is, using a deeper voice, more bravado, and patter heavy in the n-word to endear himself to his new gang friends—while Rell grows ever more concerned over the safety of his stolen kitten, and aware that the action movies he loves (“Liam Neesons” gets a shout-out, obviously) may not look so rosy when transposed into real life. Of course, Keanu is not exactly real life, any more than their sketch show is, but it does feel like an appropriate longform vehicle for some of Key and Peele’s pet concerns (pun semi-intended). Director Peter Atencio (a Key & Peele episode director, so ok, maybe some comparisons are warranted) composes his gags visually, but with more patience and build-up than a single sketch can typically allow (also way more George Michael jokes). To insist that this movie should play like a Comedy Central marathon feels, to me, a bit demanding.

There were similar demands placed on last summer’s Amy Schumer vehicle Trainwreck, which dared to place its star in a romantic comedy, rather than a vicious satire of one, and further dared to merge Schumer’s sensibility with that of her director, Judd Apatow. But Inside Amy Schumer still exists, fresh and funny, while Trainwreck offers a more satisfying experience than the hit-and-miss rhythms of sketch comedy. Similarly, Keanu isn’t intended as a bonus victory-lap movie version of Key & Peele, and Sisters isn’t meant to scratch that Parks and Recreation itch. Both movies, along with Trainwreck, explore particular aspects of their performers that makes them more interesting than the sum of their laughs, as well as more interesting than most big studio comedies.

Of course, as long as there are funny people on TV, there will be movies that don’t use them as well; I haven’t seen this past weekend’s dump release Search Party, but it stars Thomas Middleditch and TJ Miller in what looks like a Hangover knockoff—in other words, something that has almost no chance of matching their collaboration on Mike Judge’s Silicon Valley. This is less a sign of movies’ inferiority than how difficult it is, these days, to engage a talented group of writers and performers in a terrible television show for years at a time. If the Silicon Valley folks are going to lock into a TV show, it’s probably going to at very least have more going on than Last Man Standing (note: this is a sitcom that airs on ABC starring Tim Allen. You’ve probably never seen it. It just got picked up for a sixth season). On the other side, Keanu and Sisters don’t require the kind of character-building and time commitment characteristic of a good television show. They’re allowed to end, and send their stars onto the next thing.

You might also like