The Maysles Brothers Were Right

April 8-21 at Film Forum

Albert and David Maysles, and the direct cinema movement they named and helped pioneer in the 60s, had faced a backlash well before the release of their most controversial film, Grey Gardens (1976), from critics like Pauline Kael, John Simon, Jay Cocks and many more. And by the time the counterculture had turned sour and been battered into cynicism by Nixon and Vietnam, the brothers’ pursuit of authenticity had been laughed out of the academy, ridiculed by intellectuals as naive, since of course the second a camera and recorder is clicked on, or even during the planning process, a point of view is being expressed. Of the myriad exceptions to that stingy broad-brush summary of this critical detraction, the best I’ve read is by William Rothman, from his Documentary Film Classics:

Documentaries are not inherently more direct or truthful than other kinds of films. But from this fact it does not follow that documentaries are too naive to take seriously unless they repudiate the aspiration of revealing reality. What particular documentary films reveal about reality, how they achieve their revelations, are questions to be addressed by acts of criticism, not settled a priori by theoretical fiat.

So if a Maysles film would never be as politically assertive as a documentary or hybrid by Godard (an admirer of Albert’s cinematography who hired him for Godard’s contribution to omnibus Six in Paris), or as baldly self-reflexive as Jean Rouch’s documentaries, those things were still present as natural outgrowths of the stubbornly naturalistic style. And in they and their collaborators’ most ambitious films (Gimme Shelter, Grey Gardens), they’re up to things so much more interesting than tracts or navel-gazing that it seems like nitpicking to object on grounds of insincere authenticity. (Albert’s interviews, in which he often stressed the pure human reality of what their style produced onscreen, gave ammunition to detractors, but should be given secondary consideration to the art.)

David Maysles died unexpectedly in 1987 and Salesman/Gimme Shelter co-director and frequent editor Charlotte Zwerin in 2004, but Albert died only in 2015, so it’s an ideal time for this “largest Maysles retrospective in over a decade,” per Film Forum. The Dorchester, Mass.-born brothers got their real start in filmmaking after Albert had made a couple in Russia (and David had had a stint in Hollywood), when they worked for Drew Associates alongside D.A. Pennebaker and Richard Leacock on groundbreaking documentaries like Primary (1960), which employed the freeing use of mobile camera and sound equipment that allowed for a synchronous soundtrack, also being capitalized on in Quebec and France. By 1962, they’d formed the still-extant Maysles Films, Inc., and in 1963 made their first feature, Showman, the 35mm restoration of which is a highlight of Film Forum’s series, as rights entanglements prevent it from being screened regularly. Although certain rough edges (like unnecessary voiceover) would be sanded off between this and Salesman (1968), Showman is a powerful 53-minute thesis statement from the filmmakers, eschewing the direct cinema standby “crisis moment” scaffolding in favor of a straightforward portrait of oily but sympathetic American movie producer Joseph E. Levine. Minor crises do emerge, like Levine’s huckstering and successful attempt to procure an Oscar for Sophia Loren’s acting in Two Women, but there’s no manufactured action, just the push-and-pull between Levine’s basic unsavoriness (marketing trash and quality alike as equal “product” with no regard for art) and his flashes of tired vulnerability.

The Maysles cottoned early to the fact that while pointing a camera at anyone can produce drama and interest, pointing it at a celebrity has a built-in electricity (and the films are more apt to be commissioned). The gap between Showman and Salesman is partially bridged by three remarkable such portraits (along with the fun, ten-minute Orson Welles in Spain, with the master in full gather-round bloviation mode). What’s Happening! The Beatles in the U.S.A. (1964) captures the lovable lads on their first visit, shuttling between press conferences, parties and The Ed Sullivan Show, affably witty with their knowledge of their mop-topped doll-product status at this point. Intimate moments trump the screaming girls bits, as when Ringo charmingly engages with a kid fan on a train, or the glimpses of melancholy Brian Epstein, glumly discussing checking out a performance of Hello, Dolly!. In Meet Marlon Brando (1965), it’s funny and sad to watch the actor at a roving New York press junket avoid almost any mention of the movie he’s hawking (the bomb Morituri), instead attempting to engage in real (sometimes sexist) human interactions with interviewers about their own lives, and also race relations and the plight of Native Americans.

Brando and the Beatles’ somewhat self-serving “resistance” to the falsities of the consumerist machine was less of an issue for the subject of A Visit with Truman Capote (1966), with whom the brothers are smitten because, with In Cold Blood, the never-dull writer and gabber had just accomplished the goal of creating nonfiction with the shape of a work of fictional art, something to which the Maysles were becoming more and more drawn. With Salesman, the Maysles, Zwerin and co-editor Ellen Hovde found the perfect subject for their leap forward into Capote-like genrebusting, The Mid-American Bible Company of Chicago, and its nicknamed salesmen like “The Rabbit,” “The Gipper” and the central figure, Paul Brennan, “The Badger.” Their product is a gaudy, illustration-heavy monster that each assures their clients is an essential addition to a devout household, which means every attempted sale is freighted with religious guilt-mongering and the tension of the presence of these unwanted, slick-talking trespassers. Scenes of the men being goaded and bullied by management help explain why they feel the pressure to endure. Brennan, faltering in his skills and commitment, reminded the Maysles of their postal clerk father, and accusations that the filmmakers are inviting contempt for the salesmen are, I think, accurately rebutted by the counter-claim that it’s only the painful circumstances and communication breakdowns that are being lamented.

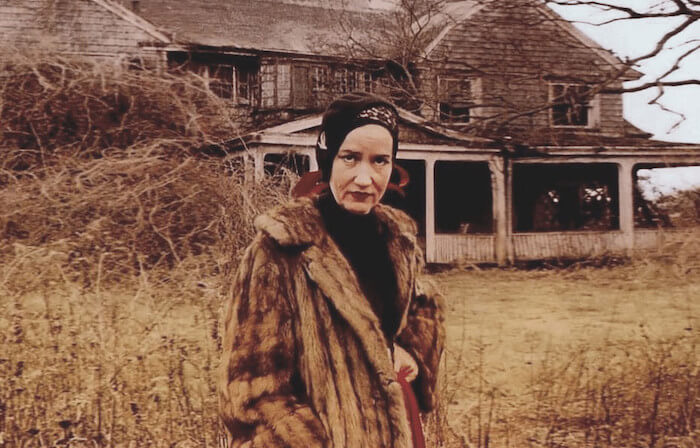

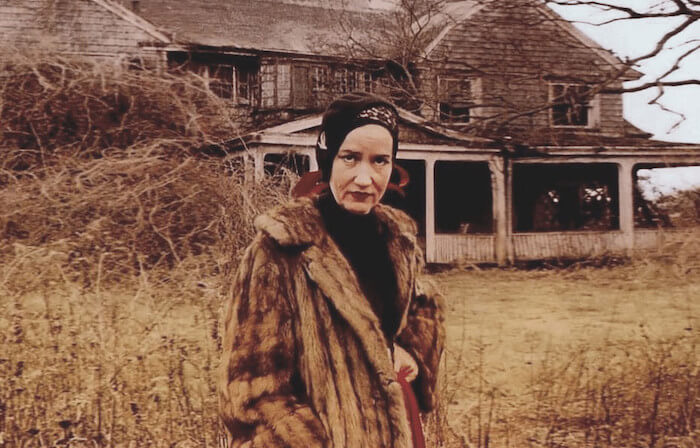

Gimme Shelter (1970) was another stylistic lurch forward for the Maysles & Co. (there’s good reason this series bears that name, as there wouldn’t be a filmography without all of the crucial collaborating, most notably in the editing room). Loose and purposefully manipulative with chronology, and including the onscreen intrusion of the filmmakers, the film pushed the limits of what a “rock doc” could be, and still shocks, both with its studio footage of the band laying down classic tracks, and the dark bleakness and moral fog of Altamont. Film Forum’s series even presents an opportunity to see it alongside What’s Happening!, a comically stark juxtaposition. The other canon entry here is Grey Gardens. The decrepit mansion that begat an unlikely cottage industry (Broadway musical, star-powered HBO movie) is in East Hampton, bought by rich lawyer Phelan Beale and transferred to his ex-wife, Edith Bouvier Beale, an aunt of Jackie Kennedy, and lorded over in disreputable glory for 50 years by her and her daughter, Little Edie. Speaking and appearing on camera without reservations now, the Maysles warmly let the duo rhapsodize about past glories (seen through crooked, fogged glasses) and blame one another for failures, while the decadently theatrical, catshit-ridden, garbage-strewn setting inserts some truths. Edie’s stubborn, glamorous pride (and scarf technique)—and a horrifying feeding of the attic raccoons with dumped-out Wonder Bread and cereal—are standouts in this horrifying classic.

The Maysles brothers’ series of films with wrap artists Christo and Jeanne-Claude are definitive, and we should be grateful that the latter teamed with such skilled filmmakers, since they were able to capture both the complicated, red tape-strewn buildups to the work and then the fleeting result (never more beautiful than in the concluding helicopter ride over Christo’s pink and green “Monet lilies” in the Biscayne Bay in Islands). There are many other treasures in the filmography, even as the work became more straightforward following Grey Gardens. Accent on the Offbeat (1994) shows what happens when two headstrong artists (Wynton Marsalis and ballet choreographer Peter Martins) from different worlds attempt to unite their art at Lincoln Center (the results are mixed, the friction mesmerizing). Martins’s insistence that “there can’t be any variables” ultimately doesn’t jibe with jazz. Dali’s Fantastic Dream (1966), though marred by cutesy narration, displays the painter’s delicate balancing act between creation and promotion. Vladimir Horowitz: The Last Romantic (1985) allows you access to an intimate living room performance by the great pianist, in a comeback of sorts after a rough patch and in his twilight years, but nimble as ever, whether playing Chopin or gently sparring with his wife, Wanda Toscanini. The sparring is less gentle in Muhammad and Larry (2009, with footage from 1980), about another attempted comeback—Ali’s decidedly losing prizefight with Holmes, highlighted by the latter singing along to a disco song about himself while driving, and later crying after so brutally felling his friend and hero.

As the criticisms of the Maysles & Co.’s arguable claims to directly capturing reality have long since quietened, and the ever-abused line between documentary and fiction has disappeared redundantly, their films can be appreciated for their artistry (the pure pleasure in watching Albert’s camerawork deserves more than a parenthetical) and subject matter alone. Questions of manipulation and exploitation now seem more naive (and dull) than the brothers’ initial idealistic aims. Their own experiments at blurring the distinctions they’d helped foster with their direct cinema associates made them allies, not enemies, of the more questioning cinéma vérité filmmakers both old and current, and now the supposed “problematic” qualities only add to the films’ pleasurable richness.

You might also like