Anti-Everything: The Crucible Has Anguish, Terror, Nihilism, and a Touch of Genius

The Crucible

Walter Kerr Theatre

219 W. 48th Street

The Belgian director Ivo van Hove has made his questionable reputation in this country by taking theatrical warhorses, or famous plays that many people are tired of or at least overly familiar with, and either ignoring the text completely or working against it directly. His conception of theater is anti-psychological and non-naturalistic and extremely perverse. Van Hove started working in New York mainly at New York Theatre Workshop, where he and Elizabeth Marvel did their infamous bathtub-centric 1999 A Streetcar Named Desire and then a very raw Hedda Gabler in 2004. In 2010 they tore Lillian Hellman’s The Little Foxes limb from limb, with van Hove seemingly deliberately miscasting the vibrantly beautiful blond Tina Benko in the role of the pitiful and faded belle Aunt Birdie.

Last year van Hove did Arthur Miller’s A View from the Bridge on Broadway in his usual destructive manner, and this won some attention because van Hove’s style is the sort that is generally confined to the adventurous Brooklyn Academy of Music. And now he returns with Miller’s The Crucible, another play that really has been done to death, and so of course people are curious about what he could have done to it. Firstly, and most intriguingly, he has placed the great British actor Ben Whishaw at its center as John Proctor, the stalwart family man who is made to confess his adultery with Abigail Williams, played by the young film actress Saoirse Ronan in her stage debut.

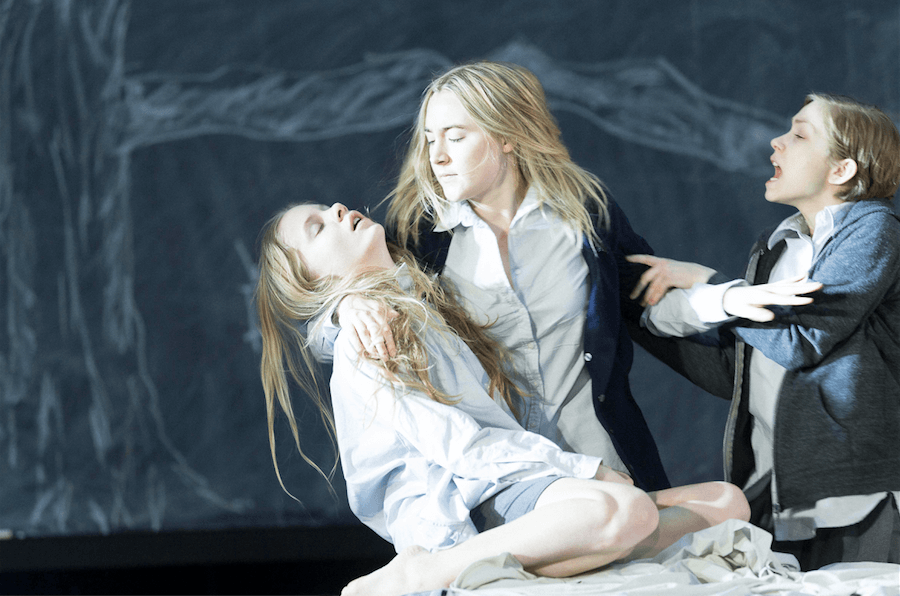

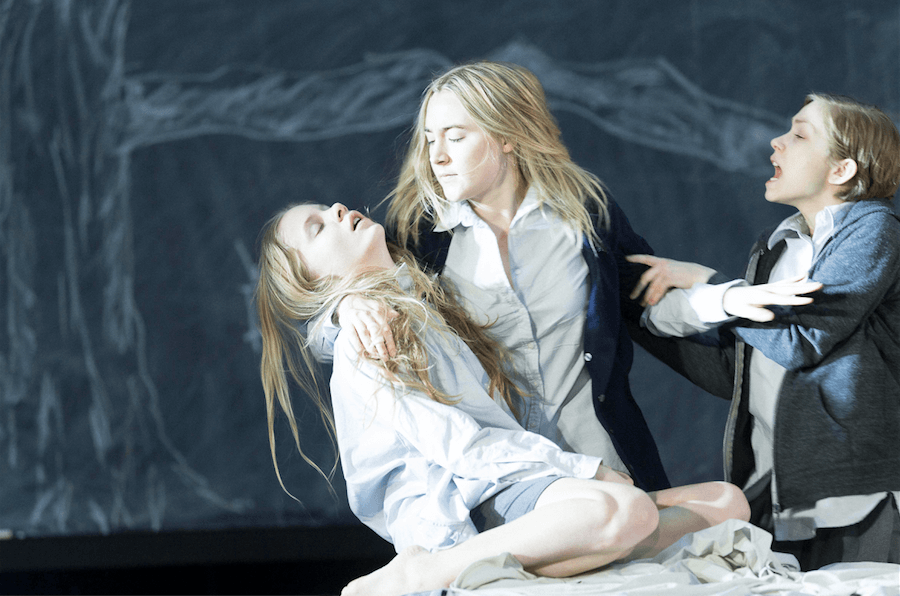

The role of Proctor goes against nearly all of Whishaw’s prodigious gifts as a performer; he is wrong for the role physically and emotionally. The surges of domineering and chauvinist male physicality with which he is made to attack Abigail and the young serving girl Mary Warren (Tavi Gevinson) are totally foreign to his sensibility, but Whishaw leaps right into them anyway and he is vocally splendid, as musical and lyric as John Gielgud. Whishaw’s talent and need is so vast that he labors with this unsuitable role and wrestles with it and finally pins it down to the mat in his magnificent last scene, where he tears emotions of shame and despair from his guts and even further below and hurls them out at us.

Whishaw was so wrecked and so involved in this last scene that snot was flying from his nose, and it was a heartening sight to see him acting with such super-intense abandon while also conscientiously and desperately trying to keep the snot off and away from his fellow actors; surely this is some of the finest mucus acting since Jane Fonda’s last scene in Klute (1971). At the curtain call, Whishaw looked so depleted and ruined that a standing ovation seemed inappropriate. Talent like this comes along once in a generation, and it needs nurturing and protecting.

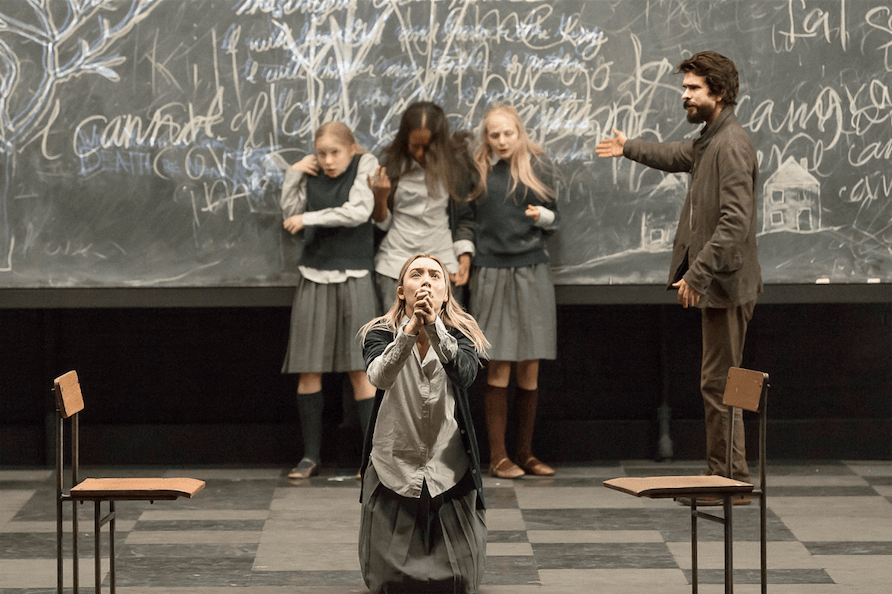

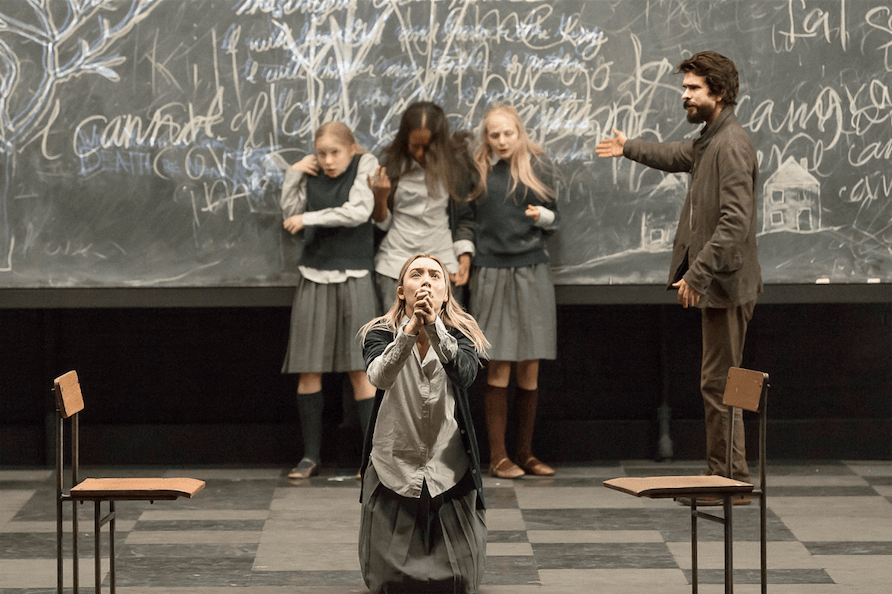

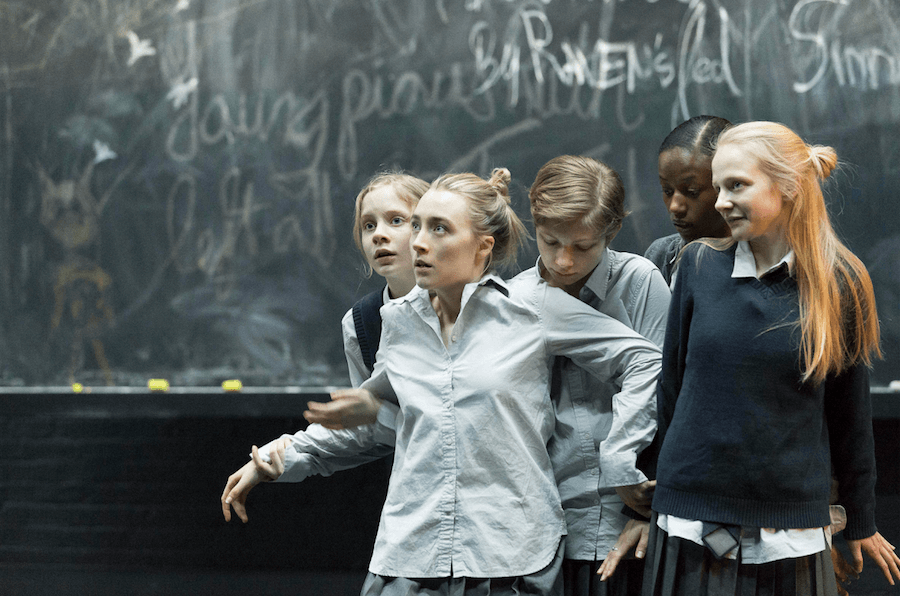

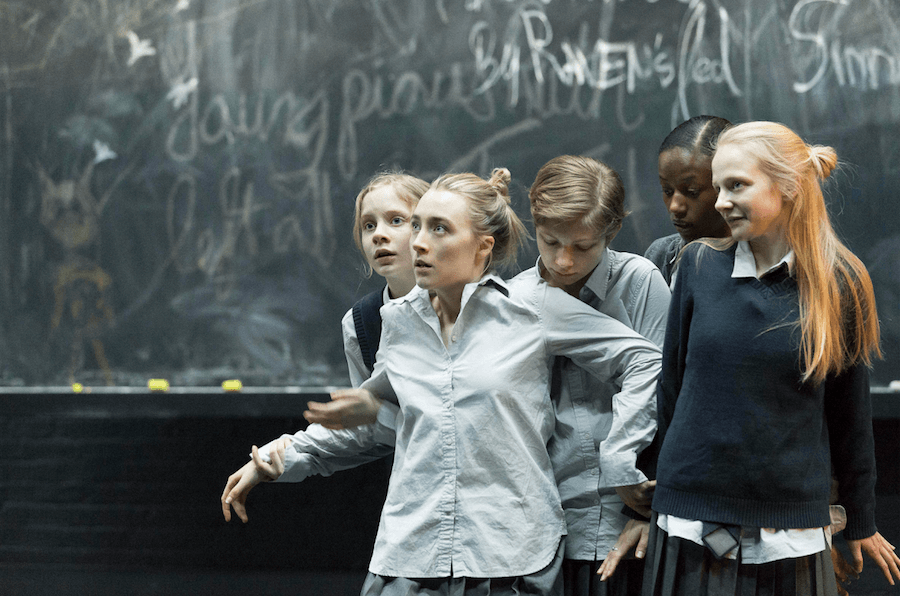

Ronan, with her sly eyes and harsh voice, makes for a convincingly demanding and power-hungry Abigail, and the other actors are very fine, but they are all caught and moved around in van Hove’s strange stage patterns, which seem to have a logic unconnected to anything beyond his own whims. He has set The Crucible in a schoolroom with lots of playing space reaching far back up stage, and when Abigail and her witch-accusing girls have their biggest meltdown suddenly the windows fly open so that smoke and a bunch of random garbage flies in and out on stage and into the audience (one of the large fluorescent lights on the ceiling also comes down and lands on stage with a menacing thump). When it comes to showmanship like this, van Hove can sometimes be surprisingly clever, but his directorial talent, if it is that, is anti-talent, willful and obstructive and finally anti-everything.

As it turns out, the end of The Crucible, with Whishaw’s immense contribution of anguish and terror, is an appropriate match-up for van Hove’s nihilism. Perhaps he has had such success with Arthur Miller lately because Miller is so clear-cut in his messages, in his laying down of the law and in his stuffy moral gravity. There is maybe some fun, finally, in seeing this director tweak Miller’s nose by giving him the full Ivo van Hove treatment, and anything that brings Ben Whishaw to the New York stage (this is his second appearance here and his Broadway debut) should be a priority for anyone interested in seeing an actor possessed of something like genius give his all.

All photos by Jan Versweyveld

You might also like