There Was So Much More to Chantal Akerman

This is the cross to bear for many great filmmakers, but the extent to which Chantal Akerman has been thought of in large part as “the director of Jeanne Dielman” is particularly criminal in its short-sightedness. Jeanne Dielman (1975) is a structural film par excellence and a desperate cry against the prison of domesticity fully deserving of its acclaim, but there is much else in this rich body of work worth exploring, from its comedy to its varied subject matter to its ideas about art and filmmaking itself. BAM’s overdue, nearly comprehensive retrospective beginning this week, headlined by a theatrical run for her final film, No Home Movie, which made its US premiere at the New York Film Festival last October, the same week that Akerman committed suicide—and supplemented by screenings of 1993’s D’est at Museum of the Moving Image, a Film Forum run of Jeanne Dielman, and an Anthology run of 2006’s La-Bas as well a No Home Movie encore—should open the door to new ways of thinking about Akerman’s work, helping it break free from a critical status quo as restrictive, in its way, as Jeanne’s kitchen.

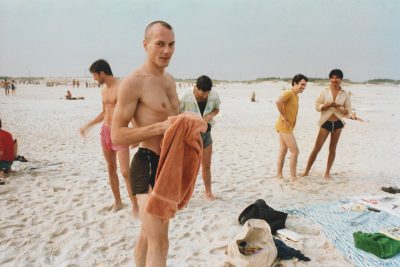

In Marianne Lambert’s documentary on I Don’t Belong Anywhere: The Cinema of Chantal Akerman (also receiving a theatrical run at Film Forum, with a week of free screenings beginning today), Akerman discusses her first feature, 1975’s Je, Tu, Il, Elle: “Each time I was asked to present my film in a gay festival, I would say no. I don’t want to take part in gay or women’s festivals. I don’t want to take part in Jewish festivals. I just want to take part in regular festivals.” Akerman was acutely aware of how eager people are to put an artist into a box and label it. Among the first qualities to be overlooked when an artist is being defined (that is, reduced) accordingly is humor, as it has been with Ingmar Bergman, Martin Scorsese, and Akerman herself. But Akerman’s humor is frightening in its precision as it illuminates and sharpens her more recognizable themes. In The Man with the Suitcase (1983), a woman (played by Akerman herself) gets a new roommate and their early interactions seem harmless enough, her small stature often squeezing awkwardly past his six-foot-plus frame or, more embarrassingly, her opening the bathroom door without knocking and seeing him naked. As the days that organize the film pass and she tries begins to avoid seeing him altogether, the laughs become much darker. In one scene, as he talks to her through a closed door, she types rapidly and randomly on the keyboard to give the impression she is working on her script. Later, he will ask her if she wants some of the ratatouille he cooked, and despite saying no, she will run into the kitchen as soon as he exits to devour it, then go back into her room before she can be seen. Before the viewer realizes it, the humor is gone altogether. The woman positions a camera facing the adjoining street and attaches it to her TV so she can watch for her roommates return, and as the title card structure jumps from the 11th day to the 26th, while she waits, we notice her room has transformed into a pigsty. She has been paralyzed, afraid to be startled by the presence of another were she to step out. Suddenly, the odd-couple happenings at the beginning read as early signs of, even catalysts for, a crippling social anxiety.

The variety of subject matter in which Chantal Akerman finds displacement and confinement is, like her sense of humor, vastly understated. The critical privileging of Jeanne Dielman and other early, “personal” work—women’s art is always burdened with the expectation of autobiography more than men’s—has dismissed her excavation of the entangling of identity and entrapment in contexts whose differences reveal new ideas, requiring the viewer to link more abstractly the subject matter to Akerman. Nevertheless, Akerman is every bit as incisive documenting issues of American politics that ring relevant today as she is in sorting through her own questions of identity and belonging on screen.

South (1999) documents the aftermath of the murder of James Byrd Jr, an African-American, by white supremacists in Jasper, Texas. Jasper has an African-American plurality, and early in the film a black woman hails the progress that has been made since the Civil Rights movement, yet Akerman opts instead to uncover its whiteness, which she locates not in citizens and attitudes but instead in place. One interviewee details how the Aryan Brotherhood methodically takes over churches and other institutions and trains followers to respond to “trigger phrases” without actually inciting violence. What is alarming is not the perpetuation of racism, but rather the Brotherhood’s invocation of America as a nation defined by whiteness; Akerman explores this through, of all things, prolonged shots of trees. As the camera lingers, the film foregrounds the passage of time such that the pasts of these trees, sites of past hangings and lynchings, become all but visible, and virulent racism seems to emanate from the landscape—from America itself. Even a paved road is corrupted with the stench and history of violence, so the film ends with an 8-minute long shot following the path in which Byrd was dragged, finding tragedy in the racialized attitudes of the Brotherhood. Few films today have so simply and so effectively captured the paradoxical state of race relations in America today, in which a de facto whiteness threatens not only lives but the sense of belonging, and therefore identity.

One need only be aware that Akerman was born in Belgium to a Holocaust survivor to know that these films, implicitly dismissed as “minor” by lack of critical attention, are oddities only on the surface and that such a quote undoubtedly links back to Akerman’s own family history. It should likewise be little surprise that she films these subjects with the same sympathy, curiosity, even restlessness, that manifest when she films her own story, as she does in in La-Bas and No Home Movie. All four films—South, From The Other Side, La-Bas and No Home Movie—offer multivalent views of displacement and the relationship between identity and race that do not reinforce the conclusions of one another but instead ask new questions by updating subject and style. La-Bas was made on the occasion of Akerman teaching a class in Tel Aviv and takes place within the walls of her rented apartment as the camera looks outside and Akerman muses in voiceover about this space, created after World War II for a specific group of people, free from oppression, that she has never called home. Here is a place where nationhood and race (or religion) are intrinsically linked, though unlike the America in South and From The Other Side, this is not a result of internal hatred and strife. Yet Akerman’s own tenuous relationship with Israel, a place where she should feel welcomed, suggests that belonging is about more than being accepted as similar “Home” in La-Bas is a rigidly bounded space, as in Jeanne Dielman, and a place where identity is negotiated, as in South and From The Other Side.

Art also was posited as an antidote to the loss of belonging in Almayer’s Folly (2011) a Joseph Conrad adaptation about a girl torn between the world of her white colonizer father and Malaysian mother. Never have Akerman’s shots been so easily described as “beautiful” as in its opening, with ripples in dark water giving way to the lurid lights of a nightclub. As a man sings Dean Martin’s “Sway,” he is abruptly stabbed by an audience member. Everyone clears, save for one on-stage dancer, who slowly walks toward the camera as she sings Mozart’s “Ave Verum Corpus” before the film flashes back. Its colonial narrative is rife with contradiction, as if embracing the insolubility of the questions posed in earlier films, and art becomes the only escape from the total loss of self and identity with which Akerman constantly grappled. Escapism is, of course, implicit in all musicals, including Akerman’s charming Golden Eighties, and the woman in The Man with the Suitcase is also attempting to flee her own entrapment by escaping into her art. In I Don’t Belong Anywhere, Akerman says that her mother took piano lessons after the end of World War II—a fact she learned only after Nathalia’s death. Jeanne Dielman, as Akerman tells Lambert, leaves no such avenue of escape open to its trapped mother. To varying degrees, Akerman’s later films seem to intuit the hidden nuances and contradictions of her mother’s experience, forging their own connections that render the more typical understanding of the Akerman oeuvre reductive and insufficient.

What Chantal Akerman deserves—what any director of a high caliber deserves—is not to be reduced to the films that exemplify a particular tendency, but to receive equal or greater consideration for the works that diverge from, complicate or even reject her most identifiable characteristics. Akerman’s films reveal a belief that looking, really looking, at something in its entirety—rare is the close-up or insert in a Chantal Akerman film—is a springboard for recognition and understanding. The least we can do is open our eyes to her work as widely as she opened hers to to the world.

You might also like