The Anti-Self Help Guru: Jacqueline Novak on How to Weep in Public

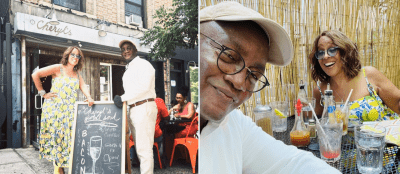

photos by Jane Bruce

“Comedy,” Chris Rock once said, “is the blues for people who can’t sing.” There’s certainly a common element in both art forms; they can both invoke the solitary act of pointing out life’s random tragedies with a touch of ironic self-awareness. A comedian, like a blues singer, must be able to entertain an audience. But a good comedian also has the ability to engage her audience’s minds and imaginations while revealing, much like a lovelorn singer gently strumming a blues guitar, a slice of personal pain. Comedian Jacqueline Novak displays that adept balance of the light and the dark with her new book How to Weep in Public: Feeble Offerings on Depression From One Who Knows.

Part memoir, part anti-self-help guide, How to Weep in Public gives its down-in-the-dumps reader a helpful guide through the emotional nadir of depression. It doesn’t offer any quick fixes or insights: “No pressure or appeals to buck up, and not a single skyward tug on a bootstrap,” Novak promises. In fact, Novak’s tome is stridently not a how-to guide to self-improvement (an admittedly avid self-help fan, Novak points out that most of the genre’s titles are written “by people who were either ‘completely cured’ or nonsufferers), but rather a reminder that depression can be an unwieldy menace—one so common that Novak reminds her reader that we’re all likely to suffer from a major bout in our lifetime. “Did you know that one in five people experiences major depressive episodes before dying?” she asks. “And with humans living longer, those numbers are probably headed the way of the herpes ratio.”

But the book isn’t completely bleak—that’d go against Novak’s M.O. Beyond the natural correlation between a creative pursuit and a depressive sensibility, Novak doesn’t strike one as being what she affectionately refers to in the book as a “depresso”—particularly not when she’s on stage. She has a tendency to own her space as a standup, walking back and forth not with a nervous pace but with a determined charge. Even on her 2015 album, Quality Notions, you can sort of hear her turning a possibly vast stage into her own personal playground. She speaks at times like a brassy waitress in an old school noir film, and though her voice might be softened on the pages of her book (a byproduct, no doubt, of its subject matter), she still has a tendency to aim high with transgressive material.

“I get a thrill out of sharing when something is a little scary to share,” Novak says when asked about what’s out-of-bounds when it comes to using her personal life for material, both on stage and in her book. How to Weep in Public, she admits, was born out of a depressive state that saw her fleeing New York City for an extended stay at her parents’ house after getting fired from a post-graduate job in advertising for not showing up. She effectively put a pause on life, and it was during those depths that she started writing. And while some might guard the facts that they went on 28-hour sleeping jags or found themselves eating ice cream in the shower, Novak sees those admissions as a part of a higher emotional truth. “The only stuff I hesitate [to share] or feel the need to obscure are times when someone insulted me, and they might find out I’m still thinking about it five years later” she says. “Typical ego stuff. The shameful stuff doesn’t really embarrass me.”

Most artists struggle with ego—a constant internal war related to identity, achievement, and success. Novak’s not immune. Novak recalls the words of Steven Pressfield’s The War of Art when talking about her struggles not just with depression but with creative fulfillment. “There’s no such thing as a dread-free artist,” she says. “Don’t think that every day when you go to sit and write that it’s weird to drag yourself there every time. If it’s important to you, there’s going to be an equally strong thing that’s fighting against it.” For her, standup serves as a sort of adrenaline kick that forces her out of a funk. “I do think there’s an element of thrill-seeking behavior as a stimulant,” she explains. “If you’re depressed, it doesn’t snap you out of it. But it can help.” She makes a quick comparison to her propensity to watch horror movies when she’s feeling low—“There’s something about them that grounds me, especially compared to the hellscape of the mind”—and the fear and dread that comes with performing usually dissipates once she’s completed a set.

And that seems clear when you see Novak perform on stage. At a recent show at Cake Shop on the Lower East Side, where Novak regularly hosts a free comedy show on Tuesday nights, she and her co-host John Early riffed on a variety of topics—non sequiturs that ranged from her fury that Early hadn’t yet listened to the Hamilton cast recording that she bought him for Christmas and that he was similarly unfamiliar with her Glengarry Glen Ross references. (When I complimented her on the show a week later, she replied, “Oh, was that the Glengarry night? No one understood what was happening. But it was still fun.”) Part of the excitement of watching Novak perform is recognizing that she’s entertaining herself, too—and that might be her first priority.

Novak’s freewheeling style works perfectly in that space, but it’s easily adaptable for a more mainstream comedy audience. She made her TV debut on The Late Late Show last November, and she had to tone down her more manic delivery and actually stand in one spot for the camera. Again, she approached it as a challenge of ego. “It was my introduction to the rest of the country,” she says. “If you walk into a party and try to be a genius right out of the gate without saying hello or taking off your shoes, no one will respect you. I have two warring sides of me; there’s one side of me that says screw it, I don’t want to make them comfortable. And then there’s the other side: you don’t want people to shut down. What is your ego worth? Those are the questions you’re always going to ask: am I a coward, or am I a craftsman?” Watching the clip of the performance, there’s a moment when Novak recognizes she’s found her audience—as well as the show’s host, James Corden, who sits at his desk guffawing —and she’s able to loosen up and “give up the goods,” as she puts it.

Novak approaches her craft, however, as an artist—and she makes an effort to thoughtfully approach comedy in an analytical way. There’s a joke on Quality Notions about what she refers to as her post-rape fantasy. The set-up is simple: “I’d walk home late at night, and I’d start to think what if I got attacked, what if I got raped?” she ponders. “Well, imagine I ran into the guy I like right after. And I’m in my torn clothes and what not. How would I look to him then? I always feel like I’m one rape away from them realizing they love me.” As one might expect, the joke has received some blowback, but Novak has made an effort to understand why some jokes are seen as “going too far.”

“If you see comedy as everything I talk about, the implication is that I believe it is laughable,” she says. “The idea of that joke is that I’m so obsessed with this one guy, that I want him to love me so badly, that I’ve having these totally inappropriate and horrifying damsel-in-distress fantasies. I’m sharing it because it’s horrible, to show how desperate these infatuations become. That’s the butt of the joke: my desperation.”

Even though she defends the joke, the grotesque extremities of her fantasy, Novak recognizes it as an example of the limitations of language within humor—particularly in the standup format. But that adrenaline rush of revealing an inner emotional truth is still present. “It’s this truth-seeking thrill,” she explains. “I know there’s something in me that feels so cathartic about comedy and I’m determined to defend it in that way.”

It’s that same force that drove Novak to write her book—not to laugh at the depressed person or herself, per se, although she certainly takes some of her own jabs. But it also exists to shine a light on something real, something that happened to her—and something that never really went away. “I’m in a much better place,” she admits, recognizing the danger of milking her depression to sell a book. “I don’t want to glorify it. It’s more my twisted version of mindfulness: you’re in it right now, but you’ll get through it.”

How to Weep in Public, like her performances on stage, almost serves Novak first—the audience second. Writing the book allowed her to understand herself and to get through her low moments; the byproduct is a charmingly and sincerely funny effort to share some personal wisdom to those who find themselves in a similar place. (And yes, she does tackle the titular action: “It’s a good reminder to those who see you, who are probably stifling their own tears, that they’re not alone in the human condition. To weep in front of strangers, it is a public service.”)

But, keeping with the notion that the book doesn’t exist to teach any lessons or offer any hopeful promises as a result of reaching its end, Novak doesn’t have an It Gets Better-style message—she’s simply glad to have accomplished a goal, and to be feeling a little better today. “Back in that place, I thought, ‘If I can only push this boulder barely an inch, I’ll still never be able to do the things I want to do. Even if I heal today, I’m already behind,’” she explains, recognizing how dealing with those feelings through sharing her emotional truth changed things for herself. “No,” she continues. “When you are in any way better, then there you are. I wrote the book almost as a promise to myself that I would be better one day.”

You might also like