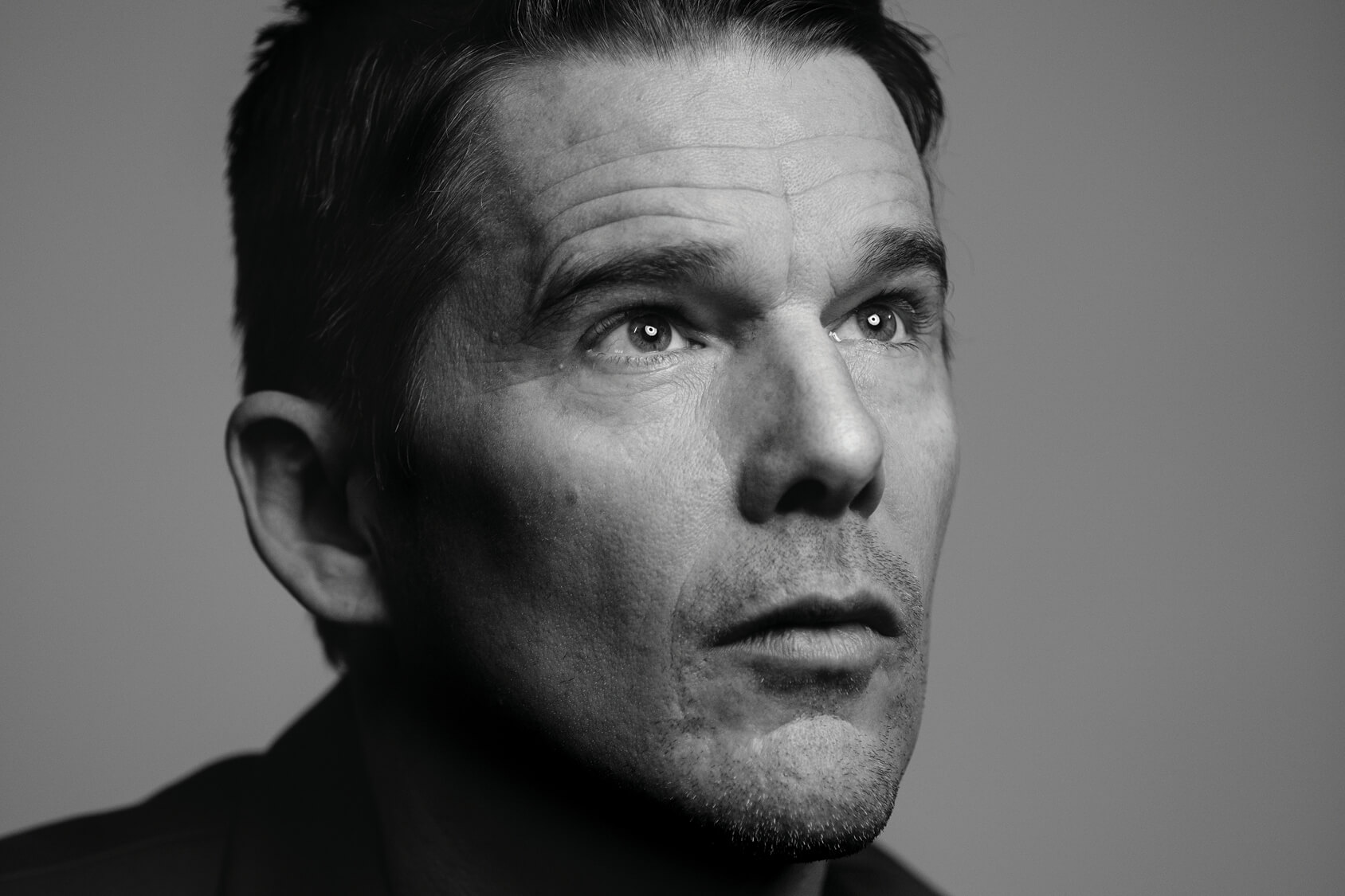

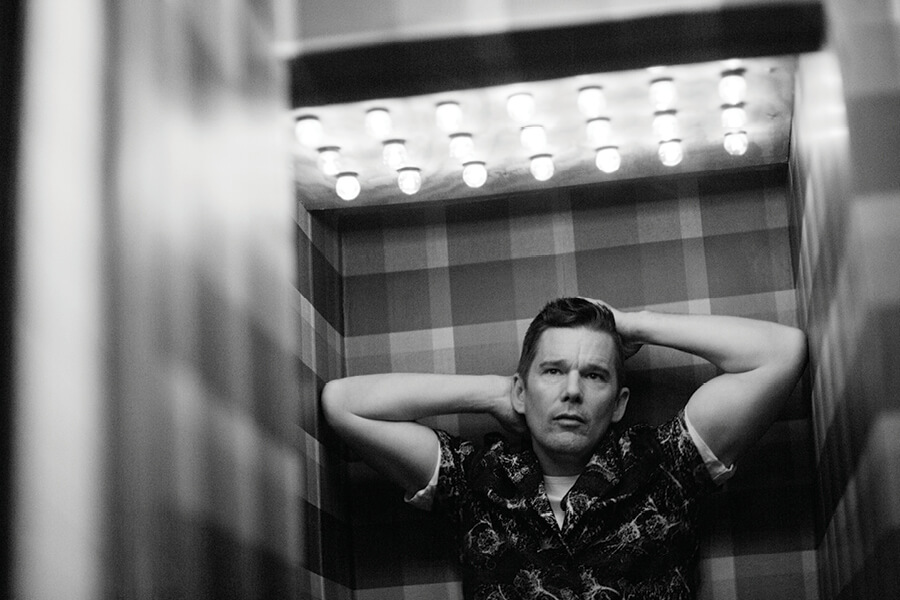

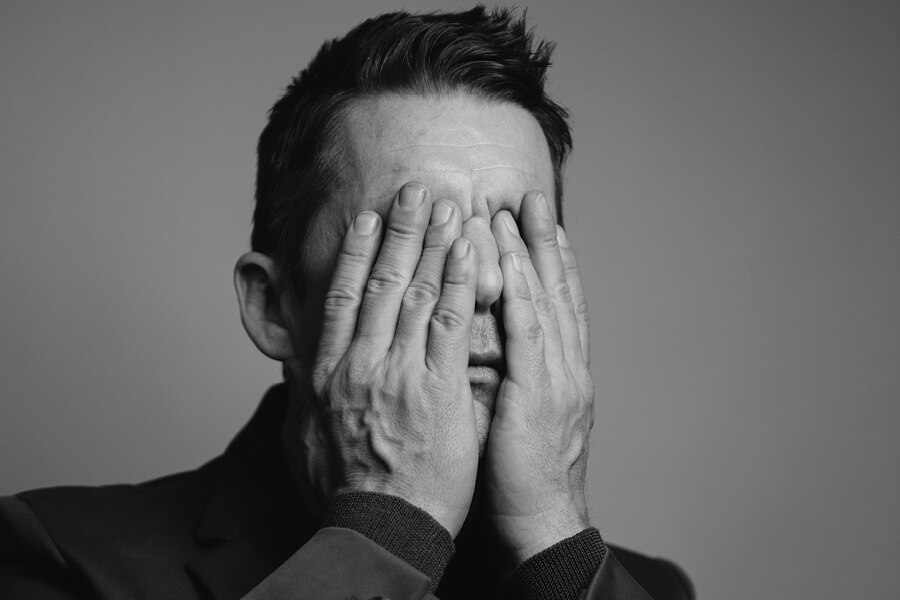

H Is for Hawke

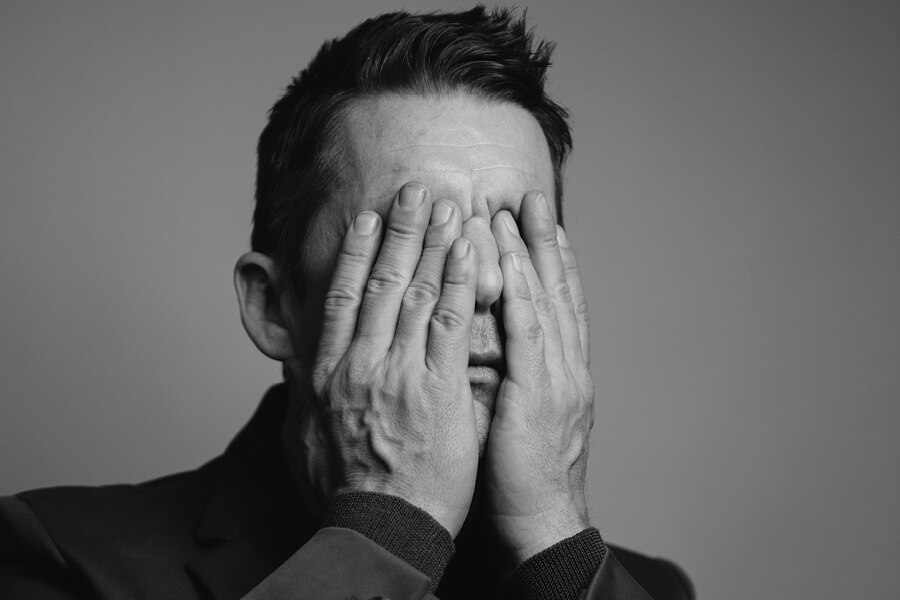

Ethan Hawke has been, he tells me, “pushed into a state of melancholy far more intense than it probably should be.” It’s a sunny January afternoon in Boerum Hill, four days following winter storm Jonas, and Hawke is mourning Nina, his black and white border collie—named after Nina Simone—who died one day before the blizzard. “You know, powerful good friendships with human beings are complicated; they can be treacherous as well as benevolent but with a dog it’s so goddamn simple. I mean, this dog just loved me. There was absolutely nothing insincere about this dog,” he tells me. “She never feigned affection. You always knew you were getting the straight dope with her. No manipulation. If she wanted food, she begged! She begged!”

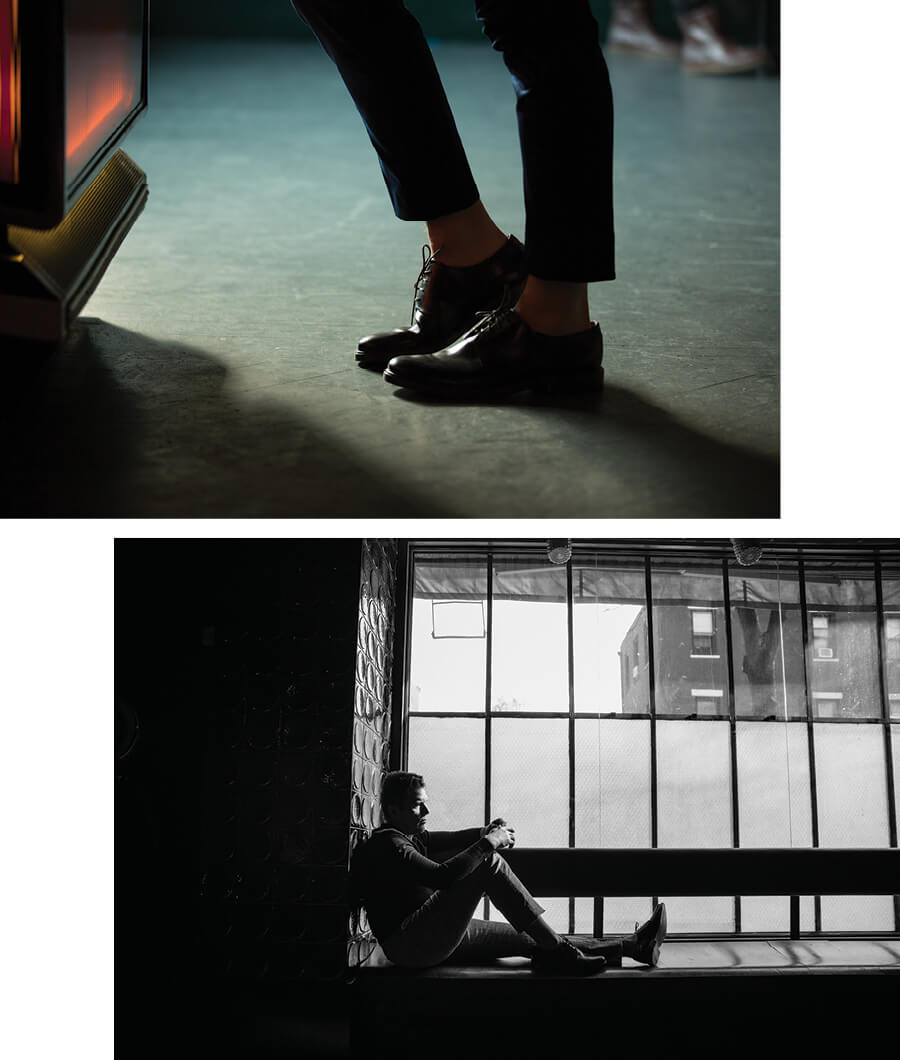

We’re walking down Hoyt Street, not far from Hawke’s home—we’ve already run into one of his neighbors, Emily Mortimer—when he chooses a random stoop for us to sit, just a few feet up from the sidewalk’s gully of gray grime and slush. From our perch we hear an index of post-blizzard sounds: shovels scraping pavement, buried cars spinning their wheels, a fire engine trumpeting its horn as it tries to plow down Bergen. “My favorite thing to do was walk her when it was snowing because she’d try and eat it,” he says, mimicking Nina’s canine enthusiasm; folding his hands into paws, tilting his head back and pretending to lick up falling snow. “She loved the snow so much,” he says. “Until they put out the salt. She hated the salt.” Hawke’s voice is gravelly—almost oxidized—with a boyish upspeak that at 45, more than two decades since his career-turning role as Troy Dyer in Reality Bites, hasn’t worn-off.

These intermittent creaks in his speech pattern, which Hawke temporarily overcame in order to portray Chet Baker’s satiny timbre in Born to Be Blue (out this month)—an expression and re-imagination of Baker’s mood more so than a clear-cut biopic—paired with a faint, bewildered glint in Hawke’s stare, give the impression he is, throughout our conversation, experiencing with recurrence, epiphanies. The kind of ideas he might pursue later, that aren’t half-bad and constitute some of his and longtime collaborator Richard Linklater’s abstract caprice. Ideas that Hawke might even jot down in a notebook he carries in his coat pocket, a kelly green Moleskine with a photo of Huck Finn scotch-taped to its front.

“I was making a movie in Montreal, and my life was completely falling apart,” he says, describing the year he found Nina on a farm. “So I decided to get my daughter a puppy for her fifth birthday.” It was 2003 and Hawke’s first marriage, to Uma Thurman, was ending, and his career had reached a haphazard juncture. Young actor with a Gen X following turned adult actor with unlikely pursuits, like becoming a novelist with his debut The Hottest State, published in 1996, followed by Ash Wednesday in 2002. Then came the huge success of Training Day trailed by his failed directorial debut, Chelsea Walls. Nina, it seems, provided some relief.

“And it’s funny. [My daughter] was going into kindergarten and now she’s graduating high school. This dog watched over my daughter for the whole of her childhood. When Nina got sick this Christmas, it felt like she’d done her job. So…” he pauses to stretch out his knees. “I’m trying to figure out what’s to be learned by all of this.”

Not entirely sure how to continue on from the topic of his dead dog, I share with Hawke how, come December, I love spotting college kids, especially freshmen, who’ve returned home after their first semester and are reunited with their childhood pets. Maybe that’s an insensitive anecdote to share, but Hawke appears to appreciate it.

“Yeah!” he nods. “They’ve revisiting their own past.”

Walking their dog, wearing their pajamas and winter boots. And even when they’re distracted by their phones, the dog doesn’t care.

“The dog is so happy to see them.”

So happy. Maniac happy.

“You should write a short story about that,” he tells me before meandering into a memory of working on White Fang (1991), his first leading role. He hopes soon to start writing a novel inspired by that experience. “What’s great about dogs is that you can’t act with them. You actually have to be with them,” he says. “The same is true for any great scene partner I’ve had. And that’s what acting with the wolf in White Fang was like. If you’re worried about what the camera is thinking, then they look at the camera.”

I suddenly miss my dog, badly. He too loves the snow. He loves dunking his head inside fresh mounds, digging for who knows what. I’m tempted to show Hawke a picture of him, our family’s welsh terrier, Willis, but decide against it. Instead we start talking about James Franco.

“It’s really interesting being older watching a young actor like James Franco give himself the permission to do whatever the fuck he wants. Even more than I do.” Hawke, whose career is somewhat genre-jumpy and all over the place, who has in the past been described as pretentious, relates deeply, he tells me, to Franco.

“Fear has been a real fuel for me. The fear of not being as good as I want to, the fear of losing the respect of people I admire.”

From Oscar nominations to B-movie flops, ensemble successes like Dead Poets Society and this year’s anticipated remake (and re-teaming with Antoine Fuqua and Denzel Washington) of The Magnificent Seven, to launching a theater company with his buddies that eventually folded in 2000, to writing novels, to running the New York City marathon (3 minutes faster than Alanis Morisette, 11 minutes slower than Diddy); to experimenting with documentary film, working with Sidney Lumet on his final project, to directing a Sam Shepard revival for the stage, to dabbling in horror like 2012’s Sinister or this year’s Regression opposite Emma Watson; to Shakespeare, to cop thrillers, to westerns like Ti West’s In a Valley of Violence, which has its world premiere this year at South by Southwest; to sci-fi and vampire fare, to committing to ambitious, decade-long character studies like playing a dad, for instance, in Boyhood or portraying Jesse opposite Julie Delpy’s Céline in the cult-loved Before trilogy, it’s no wonder Hawke, who describes himself to me as a “restless insomniac,” feels a nearness to Franco’s incoherent, indiscriminate career.

“He’s really tested my theories about that, about doing whatever,” says Hawke. “For the first time in my life I understand why I engendered so much anger in people. Why I irritated people so much. Franco made me realize a lot.”

What else?

“That the world is not rooting for you. The world is not your cheerleader. You have to be responsible for your own art and you have to go to fucking war for it. And whether you like him or not, he’s doing that. He’s fucking sucking the marrow out of life. The funny thing is, what I learned too is, that’s not James’ problem. Your feelings of irritation or hatred are really your problem.”

How so?

“Because if he keeps working at the pace he is, when this guy is 65, he’s gonna be a goddamn master. Alright.”

Or he’s going to be someone who knows little about a lot.

I ask Hawke if he’s always been someone who feels compelled to experiment with many mediums; if a connection can be drawn between his full swing, try-everything-career and some innate freedom to do so—to be rudderless.

“I feel like a cat. You do an interview and people ask you why you do things, and I feel whatever answer I say is disingenuous because what I’m really just doing is trying to stay alive. Like a cat I want to stay alert and curious. There’s some kind of shutter or blinder that you’re supposed to stay in your lane, that I just never had. And I don’t know what it is. Feelings of inadequacy? Fear has been a real fuel for me. The fear of not being as good as I want to, the fear of losing the respect of people I admire. It’s like the only thing that drives me to some discipline. I don’t know what the answer is to why I haven’t stayed in my lane.”

In what ways have you felt inadequate?

“I remember to my absolute horror, shame and rage, seeing Amadeus and feeling like I was Salieri. I was 14 years old and my parents took me to see it. I was working with River Phoenix at the time on the Explorers and I thought, ‘Oh shit. He’s fucking Mozart. And I’m Salieri. I don’t want to be Salieri!’ Because River had the stuff of magic about him. When he passed, he had so much magic dust on him that you almost felt in some strange way that it made sense that he passed. And this is a long-winded way of saying I’ve wrestled with my feelings of inadequacy as an actor.”

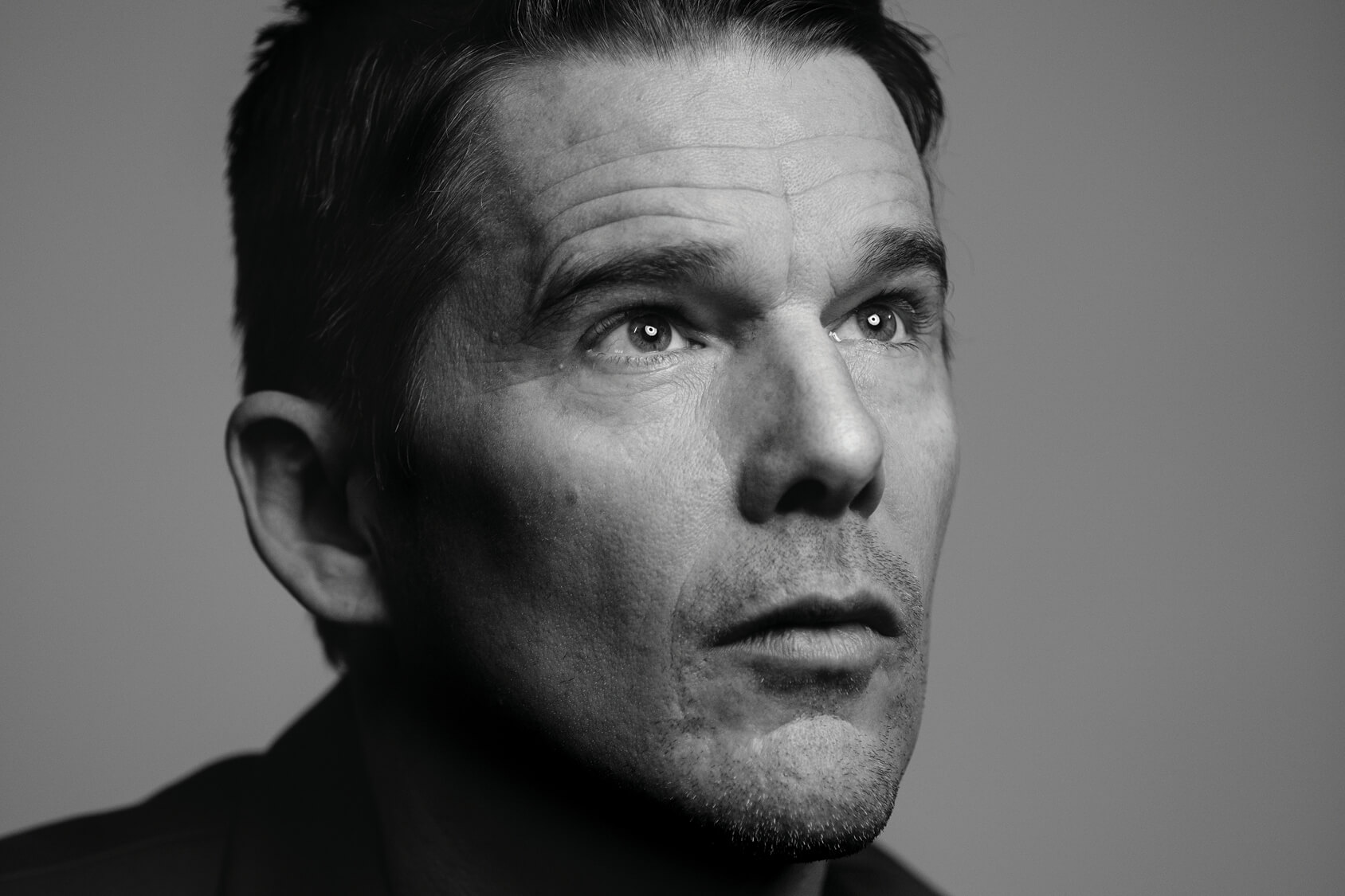

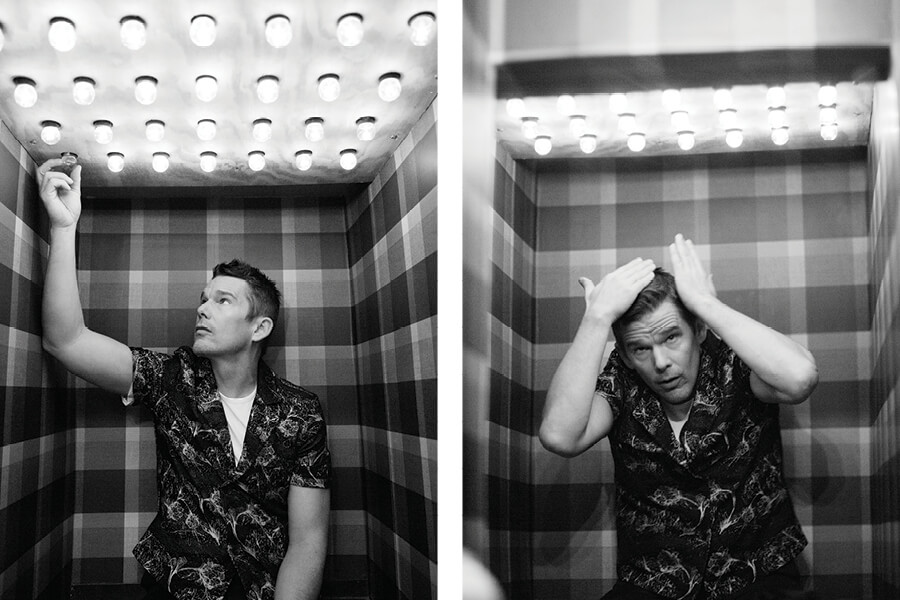

Calvin Klein

I mention to Hawke that I couldn’t help but notice in his three-decade-long career, he’s only worked with three women directors, and all in the last two years. He nods. His eyes grow big. He can’t believe it himself. He tells me he’d love to work with Kelly Reichardt, for instance, whose Wendy and Lucy he’s watched again since Nina died. And describes director, Aisling Walsh who just directed him and Sally Hawkins in Maudie, a film about legendary Nova Scotia painter Maud Lewis, as “ferocious and passionate… you could just picture her leading a rebellion,” he says. “Like she’s got an inner Irish Che Guevara or something.”

So I press.

But in thinking about how few woman directors you’ve worked with for instance, and then also, in thinking how you haven’t been obliged to stay in your lane… Do you think there is a relationship between staying in one’s lane, as you mentioned and being denied?

“Oh absolutely. Also I was pretty much raised by a single mom who thought I was… You know, I’m a classic only child in a lot of ways. I was told from the time I was a little kid that I could do anything. And so I needed the world to slap me a few times.”

T Shirt- Bespoken, Shirt- Billy Reid, Pants- J crew, Shoes- A.P.C.

Just then, a cop car slows in front of the stoop where we’re sitting. The cops arch their neck out. “Hey what’s up?” they say.

Ethan waves: “What’s up man, how are you?”

You’re kidding. There’s someone in the back of that cop car.

“Mmhmm. They don’t care,” he says as they drive off.

That’s fucked up.

“Happens all the time.”

That cops wave at you?

“Hey man, did you see Training Day? Brooklyn’s Finest?”

But those movies are about corrupt cops. Well, in part.

“You know what I mean. They’re just fans. Just cops taking that guy in the backseat to the precinct.”

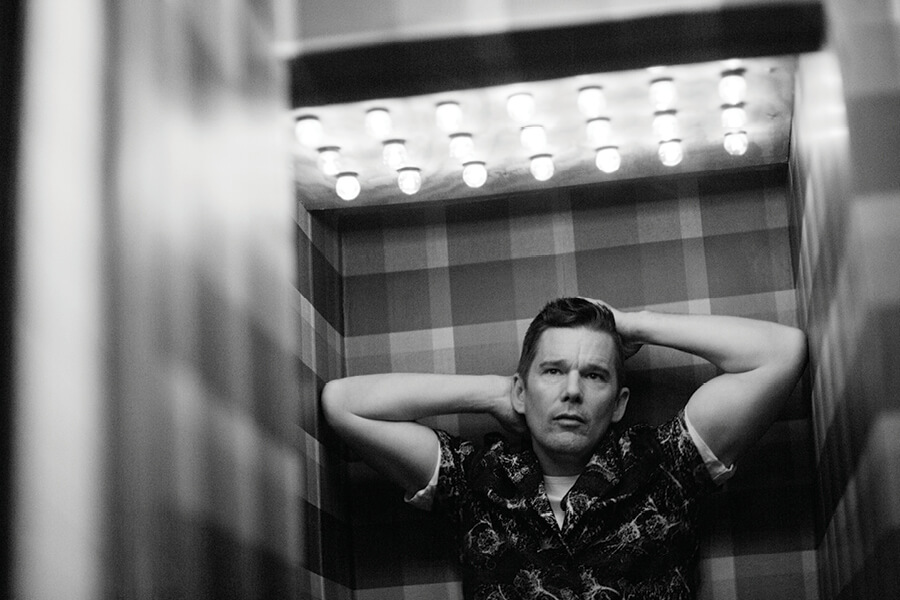

“Wanna get a cup of coffee? Let’s get a cup of coffee.” Hawke leads as we walk down a snow-filled sidewalk. He bends down and scoops up some snow, packs it into a ball and throws it at a tree. There’s a quality to Hawke that reminds me of an ex-boyfriend. He raves about Cassavetes, for instance, and references Beckett when our conversation meanders into the translation of his novels. He ranks Bukowski as a true original and quotes Brando when he explains the bond between actor and director; about “spiritually marrying yourself to your director…shackling yourself.” He counts Five Easy Pieces as “the kind of movie that made [him] want to be an actor.” It’s almost as if Hawke is nostalgic for men.

“I was told from the time I was a little kid that

I could do anything. And so I needed the world to slap me a few times.”

I think about his book, Rules For a Knight, which came out last year. A parable about a Cornish knight who, fearful he might not return from battle, writes a letter to his children. No bigger than the size of my wallet, Rules is a collection of musings on forgiveness, courage, generosity, grace, justice, and so on. A guide to life, preoccupied with the Why? of it all. A chivalrous take on how to live with kindness and compassion. It’s almost so Hawke. Which makes me think, there’s no such thing, as too Hawke.

Over coffee, we talk more about Born to Be Blue. Directed by Robert Budreau, the film functions like historical fiction, quasi-biographical, distancing and dreamy, it acquaints the audience with Baker’s later life: his struggle to stay clean while addicted to heroin, a bad beating that leaves him toothless with dentures, rendering it near-impossible for him to play the trumpet, and a girlfriend, Jane, played by Carmen Ejogo, who falls for him despite all of this. Hawke likens the film to Geoff Dyer’s But Beautiful insomuch that Dyer’s vignettes of Lester Young and Charles Mingus, for example, are evoked poetically. Dyer, like Budreau and Hawke, get at the essence and to some degree, myth of these men. It’s a film less concerned with truth-telling, but with imagining Baker as perhaps he even saw himself: funny, even when he was looking to score; charming when he had nothing to offer; bereft when he couldn’t play.

“If I lay on my bedroom floor and listen to seven Chet Baker albums, and do nothing else,” Hawke tells me, “what I’d see is something like our movie. It’s so romantic. It’s so lonely. We’re exploring the Chet Baker legend.”

Sweater-A.P.C, Trousers- Billy Reid, Shoes- Calvin Klein

I tell Hawke how after seeing a screening of the Born to Be Blue, I met up with a friend for a drink and we talked about artists and addiction, about geniuses like Baker. About feeling like maybe their genius was driven, in large part, by their addiction. About recognizing how these notions are both young and stupid. Hawke understands where I’m going with this train of thought.

“I lost two of the great acting inspirations of my generation to heroin. My interest in playing this part, is as related to Chet Baker as it is to them. To River Phoenix and Philip Seymour Hoffman. They were both really exceptional people with a really deep and powerful gift to give the world. And with that gift came a lot of… to what extent are people self medicating and dealing with depression? With River it’s different. Young people make mistakes. I mean older people make mistakes too but we’re more accountable for our decision making. With Chet it was a life culture. He didn’t think the problem was heroin. He thought the problem was the world having a problem with heroin.”

“The world is not your cheerleader.

You have to be responsible for your own art

and you have to go to fucking war for it.”

As we both finish our coffee, Hawke wonders if there’s anything I meant to ask but forgot about. I realize then, I’ve completely forgotten about my notes, which stayed tucked in my bag the entire afternoon. “Doesn’t that feel great?” he says, before scribbling his email down, just in case something comes to mind. We walk out, him home and then to his son’s basketball game at St. Ann’s. Me, to the subway. On the ride back to my apartment I think about Nina and decide I’m going to FaceTime my family when I get home and say hello to Willis. When I open my computer there’s an email from my stepmom. Her father’s dog G.G. was put down that morning. Her email ends, “No more pets. It’s too hard to see them go.”

I can’t believe it. I’ve spent the afternoon talking about mourning a dog, and well, shit. Later that evening I email Hawke. I tell him about G.G. and how unreal the timing was.

He writes back a few hours later, already at his desk, onto his next project. “That is crazy,” he notes. “I’m writing about my dog right now.”

Photos by Eric Ryan Anderson

Styled by Savannah White

Hair and MakeUp Jordan Long using SKii for StarworksArtists.com

You might also like