“Watching with a detached gaze”: The Cosmic Distance of Marker’s A.K. and Kurosawa’s Ran

Courtesy Film Forum.

A.K. (1985)

Directed by Chris Marker

February 19-25 at Film Forum

Ran (1985)

Directed by Akira Kurosawa

February 26-March 3 at Film Forum

In a 1975 lecture—reupholstered into the end-notes for his Something Like An Autobiography a few years later—Akira Kurosawa had this to say about on-set demeanor:

During the shooting of a scene the director’s eye has to catch even the minutest detail—but this does not mean glaring concentratedly at the set. While the cameras are rolling, I rarely look directly at the actors, but focus my gaze elsewhere. By doing this, I sense instantly when something isn’t right. Watching something does not mean fixing your gaze on it, but being aware of it in a natural way. I believe this is what the medieval Noh playwright and theorist Zeami meant by bon’yari shite—”watching with a detached gaze.”

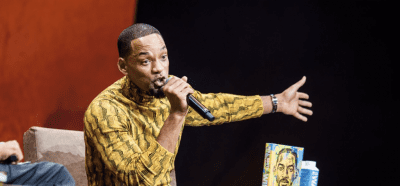

The question of Kurosawa’s gaze (by this point withered, or so apocrypha would have it, down to near-blindness) presses upon Chris Marker’s A.K., a heavy squint at the filmmaker in the throes of shooting Ran—his adaptation of King Lear—in 1985. Maybe it’s telling that Kurosawa saw fit to publish his memoirs five years before making this magnum opus to end all magnum opuses; the 70s and 80s were uncertain decades for the auteur, whose domestic profile had lapsed into unbankability at best, and self-parody at worst. (Lucas and Coppola helped pay for Kagemusha, Kurosawa’s “comeback” in 1980; both Ran and A.K. were financed in part by the French superproducer Serge Silberman.) While not exactly pilloried, Marker’s film carries the reputation of a supplemental curio—a “lesser Marker”, to the degree such a thing can actually exist. But A.K. frustrates only in the most beguiling of ways, which is to say, in the context of Marker’s overall career: the essayist is probably as deferential to this subject as Marker has ever been, referring to Kurosawa throughout the film as “Sensei.”

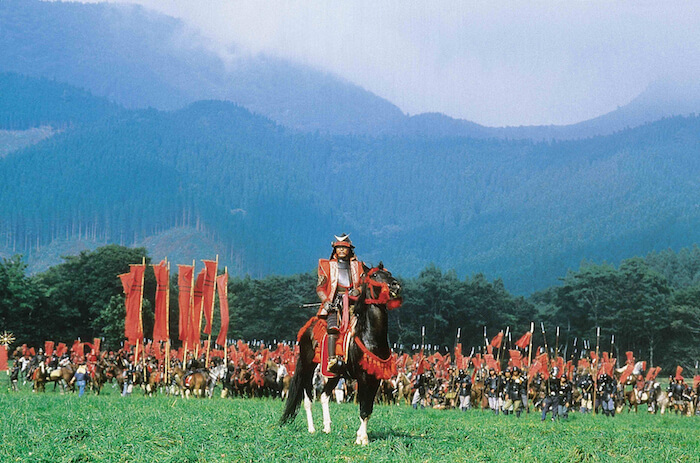

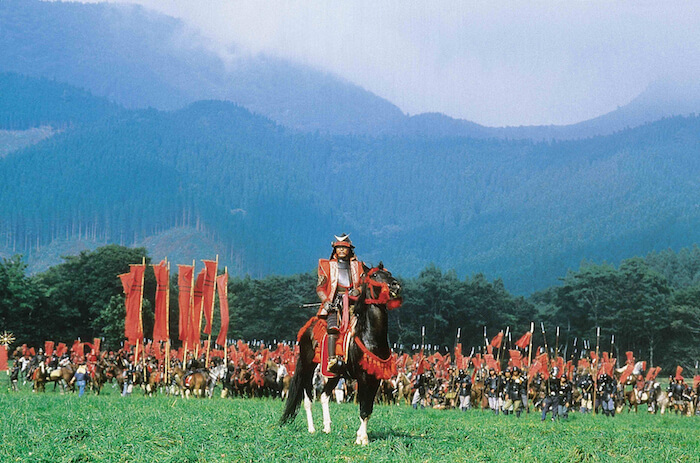

From the epicenter of a behind-the-scenes sprawl that can and should be called “epic” without a whit of sarcasm, Marker’s uneasy remove grants Kurosawa a visage of not-undue frailty, forever hidden beneath his signature tinted shades. A.K. is organized quite literally around its namesake, then, in discrete thematic chapters of no set length or query (“Rain,” “Patience,” “Horses,” etc.), taxonomizing the physical strands of Ran’s utterly insane scale of production. Kurosawa is here shooting at feudal castles erected near the sooty base of Mount Fuji, dotted with hundreds of extras wearing handmade 16th-century military uniforms, executing color-coded flag formations, riding horses imported from the United States, captured by three Panavision cameras running in sync—or as Marker’s voiceover dryly ruminates, “three different angles for Kurosawa to control; for us, three chances of ending up in the shot.” The shoot sees Marker spend as much time shooting the ruddy-faced young men playing Kurosawa’s warriors as the director himself, if not moreso. One extra jokes about how Marker’s closeups are more than he’ll ever get out of Ran, and the action halts for a freezeframe, complete with the fading in and out of an ironic supertitle—the only one of its kind to appear in A.K.—scored to 60’s yakuza-thriller style rhumba music: “The Nameless Warriors of Mount Fuji.”

Courtesy Film Forum, via Rialto Pictures.

Hurry up and wait, indeed: the bulk of A.K. surveys processes whose outcomes will be invisible to the viewer who hasn’t seen Ran. Assistants are seen sharpie-ing red and blue stripes across gigantic plastic scrims, the voiceover patiently explaining that these are designed to bounce colored light onto Kurosawa’s actors, each of whom has their own leitmotif. But the anticipated scene-by-scene comparison never takes place; we are instead left to imagine the effect to ourselves. (Whether this is a contractual obligation of Marker’s or a structural quirk goes unaddressed, beyond a vocalized imperative not to “steal” any of the beauty intended for Ran. Kurosawa’s decisions are not being summarized so much as autopsied.) Watching composer Toru Takemitsu saunter about Kurosawa’s massive encampment, witnessing the temple of Tatsuya Nakadai’s ruthless demigod Hidetora for the first time, as dusty and dirty as any of the film’s medieval characters while perhaps reconfiguring musical notes in his head, triggers something of an out-of-body experience: one of many opportunities Marker seizes to get out of Ran’s way, to beg again the question of distance between his own camera and Kurosawa’s end-vision.

The only space Marker establishes off-location is a blood-red room wherein Kurosawa’s old black-and-white films play, as if on loop, from an old television set; a hand—presumably Marker’s—replays cassette recordings of Kurosawa talking with colleagues on set. (Liminal zone? Cinephilic unconscious?) By A.K.’s conclusion, the aperture has widened enough to capture a few of Ran’s staggering choreographies in their nascent form, diegetic spectacles deflated whenever shooting is called to a halt, which is often. For all its resetting and re-rehearsing, A.K. is as termitic a behind-the-scenes documentary as exists, playing up the absurd longueurs of filmmaking while refusing any easy synecdochal auteurism—preserving the aura of cool mystery that accompanies Kurosawa within the production’s camp.

And Ran itself? By means of personal disclaimer: I first saw it on a remastered 35mm print in 2000, and left the theater convinced I had just witnessed the greatest film of all time. While this mode of list-making is less of a personal prerogative with each passing year, Kurosawa’s film continues to embody a rigor (evidenced hardest by A.K.), of light, sound and color, that to me remains unmatched, disquieting in its superhuman totality. For all the quiet stretches in Kurosawa’s Noh-inflected screenplay (cowritten with Hideo Oguni and Masato Ide), the movie is methodical but never lifeless, sweeping in moral scope but hardly reductive—a tragedy of human consequence, as glimpsed by powerless deities above. Ran demands seeing on the biggest screen humanly possible—even, for this restoration, if that means seeing it on DCP. Because “In a mad world, only the mad are sane.”

You might also like