A Tale of Two Neighborhoods: The Real Estate Booms of Dumbo and The Upper East Side

Earlier this week we learned that Dumbo—so named by artists in the 70s who wanted to give their neighborhood an atrocious name that developers would never touch (ha!)—was Brooklyn’s most expensive neighborhood in which to buy a home (2015 saw a median sales price of $1.41 million).

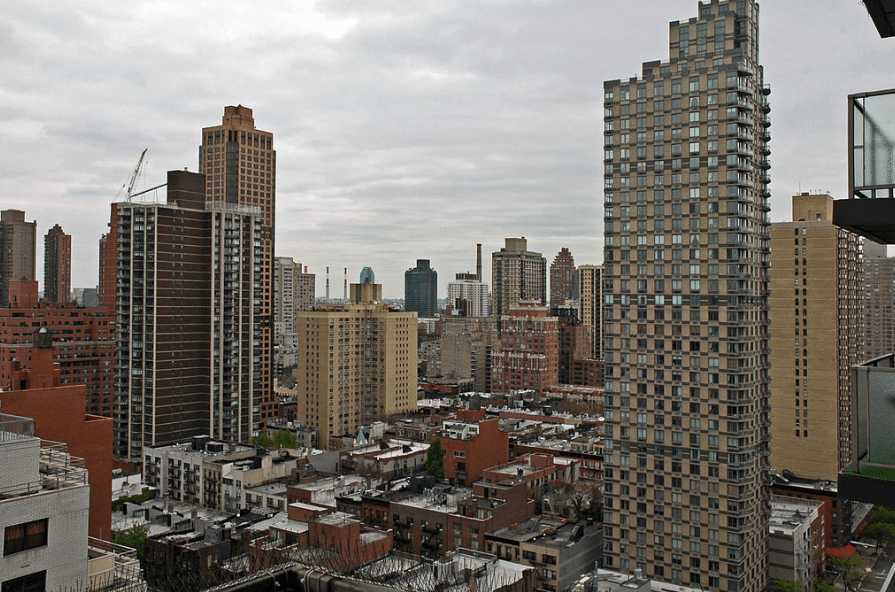

Wednesday night at 92nd Street Y, a panel of real estate agents and historians gathered to discuss how and why this happened. The panel was also there to compare Dumbo’s boom to a similar one happening on the Upper East Side. “It’s a tale of two neighborhoods,” said Christine Chen, who heads up adult education at 92nd Street Y. One, “a bastion of wealth,” the other, “historically industrial and working class.” One was developed because of its proximity to central park, the other because it was near the harbor. “Yet both are experiencing a real estate boom right now,” said Chen.

Those gathered for the presentation were somewhat more familiar with the neighborhood that hosted the event than they were with the one further south and across the river. Aleksandra Scepanovic, panelist and founder of Ideal Properties, offered a comparison to those in attendance for context: Pairing the Upper East Side with Dumbo is like pairing George Gershwin with the Beastie Boys. “Who?” someone asked. “Or the Ramones?” Scepanovic suggested. An older man in the audience stepped in. “David Bowie,” he said, definitively. Everyone got it.

The Upper East Side and Dumbo are, indisputably, very different. But each has undergone a significant transformation of its own since coming into existence. The Upper East Side—more a collection of micro-neighborhoods, said Simeon Bankoff, another panelist and Executive Director of the Historic Districts Council—extends from 59th to 96th Street, and then from Central Park to the East River. It is a giant swath of Manhattan.

Originally—after the Civil War—Fifth Avenue and Madison Avenue developed into “millionaires’ row,” though those homes were soon replaced by bigger institutional and apartment buildings, said Bankoff. Traveling east from there, businesses and structures that serviced those residents popped up, including churches.

While “all the fancy stuff” and higher-income earners stopped abruptly at Park Avenue, development closer to the river was mixed: elevated trains ran along Third and Second Avenues until the mid 20th Century; there were breweries, distilleries, and a piano factory. The population was ethnically diverse. As the 20th Century chugged along, industry and the elevated trains departed, and a new wave of development arrived. “It was no longer noxious to live next to rumbling dirty trains,” said Bankoff. High rises were not far behind.

More recently, construction from the Second Avenue Subway—planned for decades, though construction for it broke ground only in 2007—devastated retail above it, said Bankoff. Foot traffic died; businesses and homes couldn’t get deliveries. This will revitalize when the subway opens (projected for the end of this year), and people are drawn back to the area’s mix of smaller and unique businesses and amenities—not least of which are New York City’s favorite high-end grocery stores, Fairway and Whole Foods. Each now have new-found homes on the Upper East Side. No more need to schlepp west for that experience.

Giant, easily-accessible grocery stores are one thing, and significant; but the arrival of the Second Avenue subway had long pre-ordained the current twenty-plus tower, residential development-boom, underway on the Upper East Side. One that is now extending farther east than ever before, all the way over to First Avenue, and even the East End.

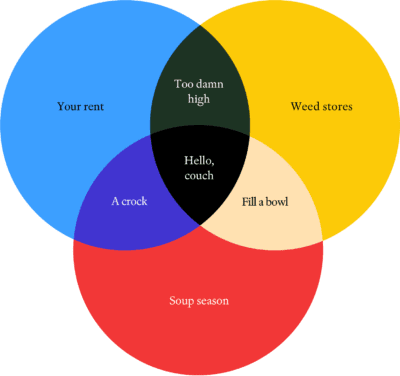

Rents still soar—around $4,000 per month, for example, just for a one-bedroom. So at that point, said Panelist Jacky Teplitzky, a broker with Douglas Elliman (who was introduced as having sold one billion dollars worth of real estate in New York and Miami), it makes sense to take a leap and buy a condo or a co-op, rather than rent (of all available units, says Teplitzky, the co-op/condo breakdown is 70 percent to 30 percent). People are no longer moving to the Upper East Side for the staid opulence and traditional life style of the 20th Century—well, not exactly—but for its various and specific, high-quality buildings, and the businesses and particular amenities that surround them. The Upper East Side of the 21st Century can place a premium not only on nice things, but on convenience. Something that brokers like Teplitzky would call “affordable luxury” living.

“My personal prediction is we are not going to see increases in (home) prices in 2016; prices will plateau,” Teplitzky said, and this after a year of fetching all-time high prices. She noted two developments near First Avenue that brokers predicted would sell for somewhere near $3,000 per square foot. “We were pleasantly surprised, all of us in the broker community, that they released them actually at $2,100 and $2,000,” per square foot, said Teplitzky; another residential conversion nearby went for $1,600 and $1,700 per square foot.

Which, you might have guessed, are price points that don’t lag far behind those in Dumbo, the Bowie to the Upper East Side’s Gershwin.

Julie Golia, panelist and Director of Public History at Brooklyn Historical Society, began by describing just how odd of a couple these neighborhoods were—first of all, by size. The Upper East Side is sprawling, while Dumbo is only 25 to 40 blocks, depending on parameters. And as originally mentioned, “It’s entire history is shaped by its proximity to the water.”

After the American Revolution, Dumbo was Olympia. At the time there were grist mills and rope walks (rope-making factories). Through the 20th Century, Dumbo was a “crucible of capitalism and manufacturing, a central place of production not only in New York, but in the world,” said Golia.

And with all that production came a lot of industrial infrastructure. “In the 1830s and 40s, it was a walled city, a wall of warehouses for storing coffee, cotton, sugar, dye, jute (for making twine and rope), salt, and dozens of other things coming in from all over the world,” said Golia. Nearby, Vinegar Hill (now the second-most-expensive neighborhood to buy a home in Brooklyn) was one of the most dangerous working class areas in Brooklyn. In the early 20th Century, three factories with more than one thousand employees were located in Dumbo, including a cardboard box company founded by Robert Gair; at the time, Dumbo was even known as Gairville.

De-industrialization hit Dumbo particularly hard, said Golia. Smaller manufacturers—makers of needles and lampshades, for example—stuck around. But Eventually, the artists moved in, starting in the 1970s, and brought with them an explosion of “avant-garde art.” Voila—the rebranding of Dumbo, and all of the cultural capital that it carries today, the kind that can fetch almost $5 million for a townhouse, had begun. In 1974, David Walentas, and his company, Two Trees, purchased 13 buildings in Dumbo, and has since rented or sold more than 800 apartments, and taken in commercial tenants like furniture makers West Elm, and the performing arts studio, St. Anne’s Warehouse, with free rent.

“The idea of waterfront as our playground is historically a new thing,” said Golia. For decades, no one had any idea what to do with the giant Empire Stores Warehouse, inside Brooklyn Bridge Park, which sat empty since 1945. Now, it’s being developed into a retail and office complex, which will include a rooftop beer garden, and—Golia Points out—even a Brooklyn Historical Society satellite museum. In 2007, Simeon Bankoff pointed out Dumbo became a historic district, so that its original industrial bones would be preserved.

Renderings from Empire Stores Dumbo.

Aleksandra Scepanovic of Ideal Properties—which she began, improbably, in 2007—moved from Manhattan to Brooklyn in 2001 and never looked back. “Dumbo has the cool factor,” she said—the kind that draws people from Manhattan, other places in Brooklyn, and the rest of the world, to buy homes. “It’s a very visceral experience standing underneath bridges, and you hear the hum of traffic. You know you’re in a metropolis,” said Scepanovic. “If you take a photo on any street in Dumbo, someone else in the world, they look at it and say, “Oh, that’s New York City.'” Dumbo is New York to the rest of the world like Williamsburg is all of Brooklyn. “People from Belgrade, Serbia, or Madrid and Paris, when you’re in Dumbo, you feel like you’re in a city, down to the core. That’s what Dumbo signifies.”

Aleksandra claimed a lot of her friends who live in Dumbo feel like they could spend their entire lives within those 20 little blocks, never leave, and feel they’d lived a very rich life, with “a great epitaph.” There is, Scepanovic called it, a “sensory overload” that happens in Dumbo, where you can “taste fabulous chocolates, or play in parks, or there is an insane river calling you,” she said. “That’s what makes this specific spot in Brooklyn one of the most amazing geographic locations that is, for some reason, being compared to the Upper East Side.”

Later, I asked about her friends’ claim, that they never had to leave Dumbo—where were Dumbo’s actual practical amenities, like a grocery store? To that, Scepanovic answered that “there is always Water Street,” and also that the Walentas family was working “very soon” on bringing other amenities. Plus, she said, she was not being literal about sticking around those 20 blocks. Simeon Bankoff reminded me that the shopping district along Atlantic Avenue was not too far away, where there is a Trader Joes, and “Sahadi’s, a fantastic Middle Easter market.”

So we’ve got our amenities partially taken care of, and the whole neighborhood is a playground, filled with the thrill and surety that, yes: this is New York. And thus, real estate prices have followed. It’s not the traditional Brownstones that have drawn buyers (none, in fact, exist in Dumbo “if we go with the purist version,” of the neighborhood, said Scepanovic) but among buyers, there is the expectation to connect with its industrial past, and the possibility to live in a redeveloped warehouse.

“There is a different sense of history between Dumbo and the Upper East Side,” said Scepanovic. “On the Upper East Side, you expect a visually opulent moment, in Dumbo, you expect huge wide plank floors, massive windows, lots of natural light, and as few columns as possible,” she summarized. “That’s what we’re looking at today, high-end, dramatic product that doesn’t exist anywhere else.”

As for those prices? What was the median price in 2003—$750 thousand—has become almost $1.5 million. And that number translates to around $1,220 per square foot “Petty cash,” reminds Scepanovic, compared to the Upper East Side.

But while Jacky Teplitzky predicts 2016 prices to plateau back west, across the river, Scepanovic does not expect the same in Brooklyn. “There is a pent-up demand for Brooklyn and the Brownstone market,” she said. “I don’t see any plateauing, or any leveling off.”

So, Brooklyn home buyers, prepare to spend more money than you already want to now, lest you are forced west—if you could imagine it—to the Upper East Side. After all, says Jacky Teplitzky, it is now “the biggest bargain in Manhattan.”

You might also like