Chairlift: Surprised By Joy

Joy is not in things; it is in us. — Richard Wagner

In 2012 I was in love, sick with it. I would walk past his apartment, chain smoke furiously, and listen to “I Belong In Your Arms” by Chairlift on repeat like it was an incantation, like he’d hear it too if I played it enough times. In 2012, too, I stopped interning at Spin magazine. I became a professional music writer. I had so much ambition I was sick with that, too—dizzy. I’d be an important critic one day, I swore. My words would hold meaning and shift the tectonic plates of culture. I listened to “Wrong Opinion” by Chairlift and sighed a shimmer of recognition. It’s how I’d always felt. I’d move the earth with my criticism. Maybe then he’d love me. But he never did. If you don’t get it, you don’t get to have it.

By the end of that year, I’d be in love with someone else. The headlong rush of my gaping ambition would trip me into a black hole of failure. All my smug, selfish assurance that I deserved endless, epic love would burn me down, a stubbed-out butt of a heart in a cracked ashtray. While this was happening, Caroline Polachek would split off to work on a solo album as Ramona Lisa and put out Arcadia. Later, Beyoncé would invite Polachek and Chairlift’s other member Patrick Wimberly to contribute to her impending top-secret eponymous pop masterpiece. I’d rebuild too, losing whole swaths of pride and confidence; dismantling old grudges and erecting new ones; arriving, maybe, in a clearing. I was stripping away layers and searching through the rubble of my failure for a glimmer of greater good. If it wasn’t self-love, at least it was contentment. If there wasn’t a surplus of happiness, there were still moments of deep joy. Then, on the day that joy felt the most palpable, the most complete, Chairlift dropped their first new song since 2012. It was called “Ch-Ching.”

***

“Looking back now on ‘Ch-Ching’ I can see so clearly that the song is about the feeling of having been invited and given the opportunity to write for Beyoncé,” Caroline says, sitting next to me on a couch in the duo’s cozy studio one freezing January day, several weeks before their third album Moth is slated to come out. “It’s funny how you can write songs and listen to them later and see so clearly that they were about something that you didn’t realize. It happens to me all the time—songs end up being sort of premonitory.”

Premonitory is what their music has always been, especially for me—prophetic almost—and Moth is no different. As I came into a job that felt like a jackpot, here was Caroline singing about her own lottery moment; as I fell head over heels into a brand new love, through my headphones trilled an album that concerns itself with nearly catastrophic joy, and parsing the inexplicable calm of contentment after years of striving, longing, and incompleteness. Something was full of heady future-pop passion, but it arrived at no conclusion—it was caught in the mesh of a still-tumbling moment. If that record anticipated a wave still on the horizon, Moth is the surf and the aftermath; the tide abating in cool, still salt.

The crest of Chairlift’s current trajectory is, of course, tied to Beyoncé’s invitation to work on her fastidiously private powerhouse of an album in 2014, one that unequivocally changed the way we understand how an album release can and should function. Aside from altering that cycle in a palpable way, BEYONCE also cemented the pop star’s status as a monolith. On top of those things, it was a desperately spectacular, excellent record—a fusion of R&B, rap, pop and what felt like extremely personal dispatches from Beyoncé’s daily life that landed like revelations. Not the least of these was track five, “No Angel,” a Caroline Polachek creation that twisted a lover’s flaws into iridescent, devilish celebration. It’s beyond a confidence boost to have one of the the biggest pop stars on the planet cut one of your tracks, and Caroline said it affirmed the duo’s entire creative process.

“I feel like it’s completely turned the world upside down,” Caroline admits. “It legitimized how we worked. I think it’s easy to not take yourself seriously, and it certainly opened up the world of mainstream pop music, which had previously seemed impenetrable and mafia-run. Instead, it was of full of humans who are real, and who I could relate to in a very day-to-day way. So in hindsight, ‘Ch-Ching’ is also about that moment in our lives.”

“It’s funny how you can write songs and listen to them later and see so clearly that they were about something that you didn’t realize. It happens to me all the time—songs end up being sort of premonitory.”

Chairlift’s release of the jittery gleeful “Ch-Ching” coincided exactly with the announcement of my new role as music editor, here, at Brooklyn magazine. To say my career trajectory had been a jagged one before this position is an understatement, but what I’ve already found here has offered the same kind of peacefulness that can be found throughout the rest of Moth. One of the album’s key tracks is the supple, jazzy “Polymorphing,” a song about getting thrust into something even better than what you imagined for yourself. There’s somethin better than what you’re askin for, kid Polachek promises, and that’s what this place was already becoming to me. Even the chance to interview Chairlift and write a cover story on them was granted to me without question—I was trusted. So I began to trust myself.

***

On the day of the interview I dressed carefully, mentally rehearsing questions in my mind, eager to scout locations for the accompanying photoshoot. Mostly, I was thrilled to meet the band who’d soundtracked the majority of my New York experience as a music writer, who’d put out one of the records that made me determined to stick with this intense, unreliable, often thankless vocation, and to share our subsequent, parallel joy in recent developments. I didn’t actually learn until she casually mentioned it during the shoot that Caroline had recently been married, but nothing could’ve been more indicative of Moth’s deeply settled peacefulness and freewheeling adoration.

The interview and shoot were to take place at Chairlift’s personal studio and homebase, a converted room in a huge and bizarre communal building on Flushing Avenue that’d previously housed the pharmaceutical company Pfizer’s entire operation. From the window in their own little enclave on the second floor, Wimberly pointed out a row of houses across the way that the company had built to put up their employees. “They didn’t want anyone to leave,” he laughs.

The room the two of them chose—almost three years ago at this point—was previously the Human Resources headquarters for Pfizer back when the company was in operation. Accordingly, they jokingly dubbed their version of it the CRC, Colleague Resource Center, and it seemed likely that the space had been designed with the purpose of making people feel trusting, at ease with being vulnerable. Or maybe it’s just that the room is pulsing with calm, creative energy, from the low, unassuming couch, to the countless instrumental contraptions, amplifiers, synthesizers and other production and recording equipment that’s strewn about. It immediately reminds me of the choir room at my high school, a haven for misfits and art obsessives to escape the sometimes-vicious hallways and seek solace in music. It’s nice too, to see the equipment spread out somewhat haphazardly, not kept spotless and barely used in a sterile studio.

The studio feels just as essential to their creative process as the musicians themselves, and the duo explain that they began to work seriously on Moth by spending a whole week locked in the CRC, creating a brand new song each day. They opted to make this album without a producer, but credit Dan Carey’s careening, off-the-wall approach to recording for some of the experimental tactics they adopted. That playfulness seems so playful across the album, particularly on the do-or-die daring of their second single “Romeo”’s film-noir pop, an ‘80s-infused clear call-back to Something’s “Sidewalk Safari.”

“One of our favorite people in the world is Dan Carey who produced our second record with us,” Patrick says, “and he was someone who was always thinking outside of the box. Like when it came time to record the vocals for “Sidewalk Safari,” instead of doing them on a regular studio mic, and a vocal booth, we recorded them in the front seat of the car. It’s a song about driving, isn’t that how you want to do the recording? So that’s actually how we recorded the song. Sidewalk Safari. His desire to experiment and build new instruments and to really push the recording process outside of the norm stuck with us on this record. Even though we were making it without him, our studio was very much inspired by him. We spent a lot of time inventing different processes of processing sound.”

The setup of Chairlift’s CRC feels like a newly invented space, one of many fledgling creative endeavors embedded in the rest of the building’s weirdly vibrant ecosystem. Construction and art studios butt up against film crews and other entrepreneurs across its seven or eight expansive floors, and after a bit of brief wheedling, the building’s manager, a formidable, intelligent man named Gotham (who I find out later is a rapper in his own right and previously ran a label) takes us on a quick tour of the different locations throughout the building where we can shoot. It’s always interesting to watch people who are used to arranging their image for public consumption sit for portraits; these two are a decade in, so the photos are exceptionally beautiful and come quickly. As we move from room to room in the old factory, both of them play with the acoustics of every new location. Caroline, especially, throws her voice out into each space to explore. It’s fascinating to consider that’s the primary way she encounters the world around her, like it’s an ever-present sounding board, a potential echo for her startling, operatic soprano. Oddly enough, my bank calls me with warnings of fraud on my account while we’re finishing up the final shots. It’s the only time I’ve ever been even vaguely annoyed at their meticulous protocol, and I barely notice the decision to close my old card, have a new one sent. It’s time to talk. This is my favorite part.

If this were the part where a magnificent, hour-long conversation with my favorite band appeared, I would consider this profile a success. But that file is lost to an iTunes syncing fluke, not even twelve hours after it took place, and I spent the next twelve trying various audio recovery softwares, bargaining with the universe and desperately trying to recover the interview. It is lost in the ether. I will say that it was without a shadow of a doubt the best interview I’ve ever done in my life, and the electricity of it stayed with me for so long that I absentmindedly walked the wrong way home, and later, took the wrong train to a long-standing weekly appointment. We talked about early Brooklyn and their relationship to the changing scene, sharing black mold-filled studio spaces with their then-idols Grizzly Bear, the building of CRC their current homey studio, writing pop songs about deep-seated joy instead of infatuation or heartbreak, those weeks working with Beyoncé, the intensive week behind most of the songs on Moth, and the merging worlds of indie and mainstream pop. At one point, Caroline and I cried over a shared sense of music’s overwhelming ability to move us outside of ourselves and up into the marvel of a greater universal force. All of this, and more, I I remembered reading in Mary H.K. Choi’s Rihanna cover write-around late last year that she had once lost a similar conversation with the Barbados star, and wondering what kind of self-loathing a mistake like that would bring. Now I knew. But I don’t consider the fact that our conversation no longer exists to be a failure.

Even if the record of our conversation was gone, my memory of it isn’t. My experience was intact, and so was theirs. The band graciously granted me another half hour or so by phone just a few days later, and even if the answers rang hollow, shadows of a conversation full of light, both of them expressed regret and empathy for the loss of the first interview. Maybe this should’ve made me feel worse, but instead it made me feel better. They felt it too—the goldenness of that time was real. And even if the random cruelty of technology and time had taken part of it away from me, a lot of it still existed. It was C.S. Lewis who first introduced me to the concept of “the memory of a memory,” and that’s how it felt, now. Simulacrum that it was, it remained.

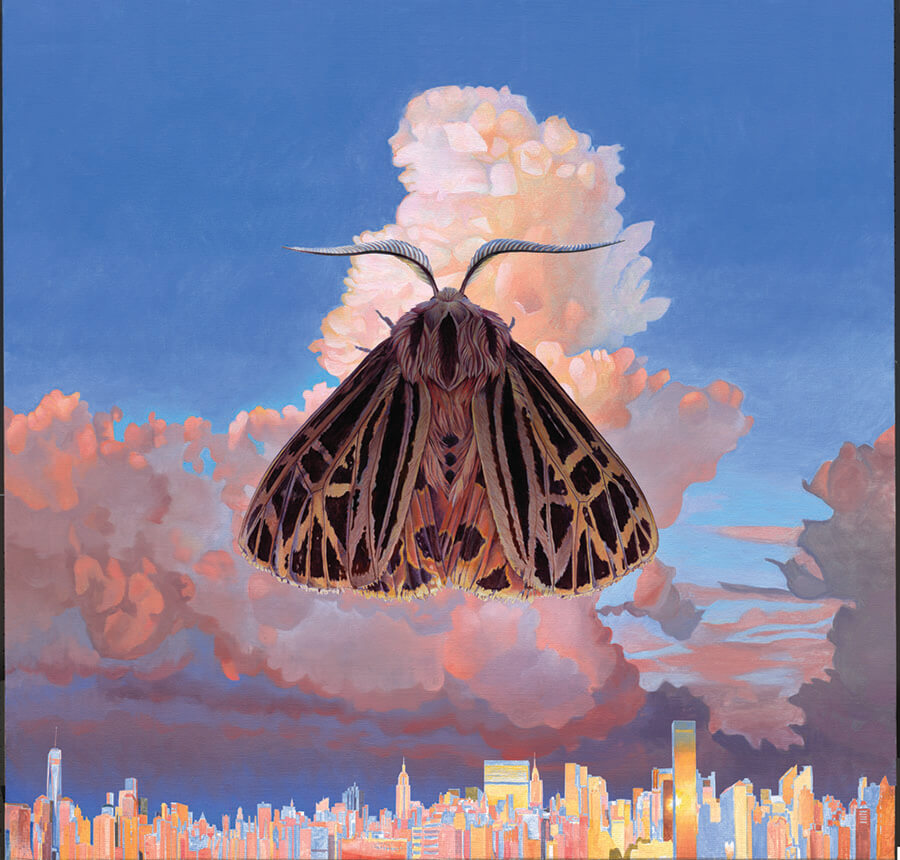

Shadow and light are everywhere on Moth, an album inspired by a creature whose defining feature is an instinct to gamble everything for a moment of brightness. “Moths are so relentless and impulsive, and as the cliché goes, they do things that harm them,” Caroline says, when asked about the album’s iconography. “They fly into walls, fly into flames, fly into electric lights that zap them. And sometimes, that’s a relatable feeling: that your instinct is telling you to do something that’s not the best idea, or that you’re not even in control of it. But for us, the moth symbolism is the most meaningful because of the vulnerability and optimism of this tiny creature. And a moth is a creature that wouldn’t survive very long in New York city right now, but you see them. And I can sort of relate to them sometimes, a soft thing in a hard place, that just keeps going and going.” The album’s staggering watercolor cover was done by Rebecca Bird, an artist who the band had previously worked with on their “Amanaemonesia” video. A moth appears against a summer sky, much larger than the city landscape behind it. Here is the soft thing in a hard place; the soft thing looms enormous over the city that contains it, or is that just perspective? In the painting, the city and the moth are as a big or small as we want them to be.

“Moths are so relentless and impulsive, and as the cliché goes, they do things that harm them. They fly into walls, fly into flames, fly into electric lights that zap them… that’s a relatable feeling: that your instinct is telling you to do something that’s not the best idea, or that you’re not even in control of it… I can sort of relate to them sometimes, a soft thing in a hard place, that just keeps going and going.”

The hardness of New York is touched upon several times on the album, which kicks off with “Look Up,” an examination of the existential, often deadening aspects of metropolitan life, and the realities of living amid tall steel and swaying bridges. But beyond that, it addresses how the universal always exists, at its core, as the personal, how the possibility of enormous success is at our fingertips here at any moment, and what it feels like to live inside that potential. “The song sort of functions like a sequence at the beginning of a film,” Caroline said. “It’s sort of like the beginning of a rom com or something, where you’re looking at the whole galaxy, then you zoom in to planet earth, then zoom to New York City. It’s bringing things into scale for the beginning of the album.” And if the opening track is the galaxy view, then it’s the album midpoint that gives us the crux of this love story, the stunning “Crying In Public.” There isn’t anything more New York than being stuck out in the wild of the city, moved to tears by the daily circumstances of life here.

“The beat for ‘Crying In Public’ started as a joke made by our friends in an amazing New York band called Ice Choir,” Caroline explains. “Those guys are 80s pop aficionados, and they coined the term ‘breezin’’—like with an apostrophe at the end—for a certain genre of music that had this sort of shuffle, triplet flow, for example Michael Jackson’s ‘The Way You Make Me Feel’ has a breezin’ beat, this ‘chockata chockata chockata.’ During this period, Patrick and I had agreed to write a song a day, and we thought it would be really funny to make a breezin’ song that day. So we started playing with that beat and seemingly out of nowhere I started singing the chorus lyrics. I almost never have lyrics right away. That song felt very serendipitous and natural.”

The tears on “Crying In Public” well up from a place of joy, not loss, an inability to keep happiness in. It’s such a singular moment, full of resilience and freedom; a glancing bit of euphoria over that galloping, old-school beat and bassline. The gamble pays off, and the brightness becomes not an inevitable light at the end of the tunnel, but a soft glow that infiltrates reality on album closer “No Such Thing.” The final track takes apart all the joyous mythology of Moth and alights back into reality. “It’s about really committing to someone,” Caroline says. “Accepting that it’s not going to be perfect, and accepting that there are probably challenges coming that you know nothing about, but that the same simplicity and beauty of something is worth the sacrifice and dedication. It has so little agenda compared to a lot of other songs on the record that sort of demand that you listen right now. It’s my favorite song on the album, I think because of the actual peacefulness that you can feel in the music.”

***

After the interview, on that wrong walk home, I realized the street was inextricably tied to another interview, one I’d feverishly conducted on a nearby corner several years ago using a woefully fresh-cracked iPhone. I remembered the fight I’d gotten into with my then-boyfriend, the rage and fear and frustration I’d felt both with our spoiling relationship and my toehold of a career. The desperation of that girl felt so far from my current jubilation. I sent a victorious text out to a different, new love, certain of our shared happiness in my success. This would be my first extensive feature for the new site, and for this one, I wouldn’t make it personal. I’d just do a straight-up profile of the band and shirk my usual practice of filtering the music back out through my own experience. Recalling that determination, after the fact, seems strangely prescient. In another way, so did the subsequent slippage of that other new love over the next few weeks. Not everything gets a happy, romantic ending just because an album you love does. Not every loose end is meant to tie up in perfectly kept time. Sometimes breezin’ is just a musical trope, not a message from the universe.

“Accept that it’s not going to be perfect, and… that there are probably challenges coming that you know nothing about, but that the same simplicity and beauty of something is worth the sacrifice and dedication.”

I often describe what I do as “emotional reporting,” the audacious idea that my deeply personal, individual experience with the music is just as worthy of sussing out as the stiff, factual objectivity we’ve been taught reporting must be. I believe relaying my own interaction to be a valid and important practice, but it also draws loud detractors. Sometimes, their constant drone about my apparent self-centeredness gets into my head. If anything, the lost file felt like the universe’s gentle admonishment of that reaction. If I’m going to articulate the importance of emotional reporting as a valid form of music criticism, why undermine myself at this crucial point? If I was really going to embrace joy and trust myself, that meant not dwelling in this failure like it was a microcosm for my entire character or symbolic of my entire career. One of my favorite poets is Elizabeth Bishop has a poem about loss called “One Art” that ends with the desperate directive — Write it! — a line that creeping back into my head as I worked on this. The loss was suddenly part of the reporting, and this story was just as essential to my profile on the band as the words I had lost.

So, I could hate myself for the random mistake of losing the initial interview, or I could choose to retain the joy that I’d experienced doing it. It had never occurred to me, before this experience, that joy was just as much a choice as anything else. Joy is not a condition of success or love, as much as it is a chosen outcome. You have to be ready for joy, too, you have to embrace it. In that realization, I grasped something about Moth that had previously eluded me. Lewis once wrote that “joy is never in our power,” but I think, perhaps, it is. We can sit and measure our grief and our loss endlessly, and tie joy to the uncanny peaks of random acquisition, or we can recognize that joy isn’t about accumulation at all. It’s about gazing at what you already have with full knowledge of what you’ve already lost, and complete acceptance that you may lose all this, too. Joy is to live with this realization and still choose to take the risk. Joy is the abandonment of known fear. Lewis also wrote “the universe rings true whenever you fairly test it,” and for all the fear and loss I’ve grappled with, I have still found the universe to be full of more kindness than hatred. A fair test still yields a world designed to encompass our joy. How would we recognize joy without knowing the dull ache of its absence? Loss leads us to back to it, in inverse form. Better: We are never finished with our joy, or with our loss.

Right before the album ends with the sweet, bright peace of “No Such Thing As Illusion,” there’s a song called “Unfinished Business.” If love has a sound, it must be what Caroline’s voice sounds like on the chorus; so full of emotion it almost breaks, so full of memory, love and hope it almost lifts you out of yourself. I’m not finished with this, this thing between just you and me, she sings. Let us all cling to all our loves with this same kind of determination. Let us never finish being surprised by joy, no matter the loss that accompanies it.

Moth is out tomorrow, 1/22 via Columbia Records. Get it here and read our review here.

All photos by Jane Bruce.

You might also like