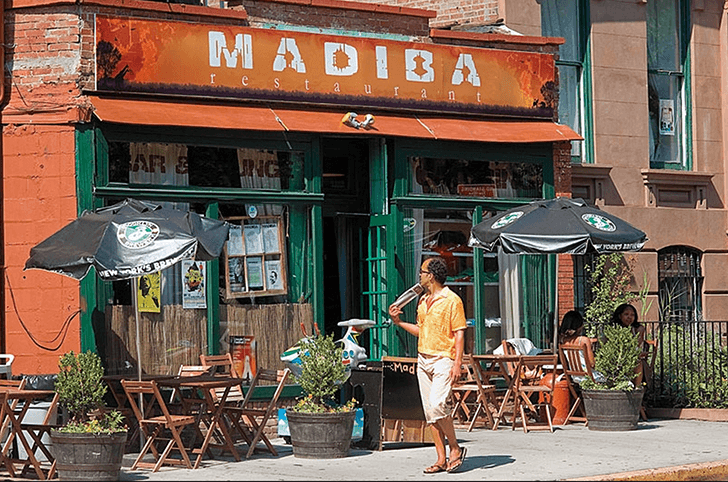

It Takes a Village: Saving Fort Greene’s Beloved Madiba Restaurant

“Only when the last tree has died and the last river has been poisoned and the last fish has been caught will we realize that we cannot eat money.” So reads a sticker haphazardly placed on the metal gate that separates the lounge of Madiba from its dining room. It’s lost amidst the curated clutter of woven dolls, dusty pelts, and contemporary Nelson Mandela portraits; it’s just one more thing in a space dominated by conversations amongst restaurant-goers and the lighthearted banter of employees that fills the room. It’s not until the natural lulls of conversation occur, during which time you might find yourself surveying your surroundings, that this Native American proverb resonates and hits a nerve for those patrons aware of the precarious condition of this beloved Fort Greene restaurant.

On November 27, the Save Madiba Brooklyn campaign went live on Indiegogo to help raise $200,000 to save the more-than-17-year-old restaurant, specializing in authentic South African cuisine and offering a solid community-as-family vibe. The campaign’s page details that the risk of closure is the result of an accumulation of issues, like the closing of their Harlem location in 2015, a “questionable lease renewal,” and of course, increasing rent. Madiba’s situation isn’t new—plenty of Brooklyn bars and restaurants in the past year alone have been forced to relocate or succumbed to closure—but the potential loss of a restaurant that self-describes as “a place of love” and has been consistently active in its community outreach and support feels particularly devastating. And yet, at what point should it be a community’s responsibility to stop mourning the loss of their favorite dives, shops and restaurants and start advocating for the longevity of these hallowed places?

The name Madiba comes from a Thembu chief who ruled in Transkei, South Africa, in the 18th century, but is now more commonly known as a term of endearment for Nelson Mandela, who as a revolutionary, statesman, liberator, South Africa’s leading emancipator, and its first black president was the inspiration behind the restaurant’s tender and jovial vibe that South African owner Mark Henegan and his brother, and manager, Denis Du Preez wanted to—and did—create.

“[We] tried to do somewhat of a teardrop in the sand of what he pretty much did–no comparison–by trying to live under his ideals in people,” Du Preez says. “We believe we all bleed red. We adapted to his ideals, and the ripple effect that Nelson Mandela created wasn’t only inspirational, his spirit is in this restaurant somehow. I really do believe it is because [even in] such a [high-]pressure business, you can still take a step back and feel the love in the room.”

Madiba staff from 2012 via Facebook

Modeled after a shebeen, the dining halls in South African townships that took the shape of makeshift taverns and mainstream venues meant for relaxation and socialization after work, Madiba has grown to be a sanctuary for those looking to lose themselves and find themselves in the South African experience. Its chill yet festive atmosphere is nourished by African pop and rock; it’s a place where one can be introduced to a range of Xhosa and Zulu music, like that of South African freedom fighter and singer, Miriam “Mama Africa” Makeba, while still getting a splash of popular Western music here and there. Its vibe is reminiscent of Cheers, that is to say that everyone at one point will know your name, and you can expect to be greeted with a handshake and a hearty smile upon entering the green wooden doors, and later walk out feeling like you’ve been adopted into this close-knit family of stragglers, Wall Street suits, Afrocentrics, and more.

Beyond unifying the different cultures—Cape Malay, Greek, Durban, English, and Portuguese—that make up the nation in their dishes, Madiba pays homage to Mandela’s legacy by empowering the different groups and individuals in New York and back in their home country not only through monetary donations but also via opening up their space to charities and Brooklyn school programs. Almost twice a week, Madiba plays host to students of all ages who visit during school excursions for the purpose of getting an in-depth look at South African culture which goes beyond the filtered versions found in textbooks.

“They hear the stories and legend that is South Africa: the good, the bad, and the ugly. The kids don’t want to bloody leave, and kept whining to stay,” Du Preez says. “That’s why I can’t let go; there are too many factors involved. This means too much for too many people, inside and outside the restaurant. People have gotten married here five or seven times. There are too many things that are left to happen. There’s just too much.”

The closing of a business or restaurant is not simply a rookie mistake, despite commonly cited statistics like “nine out of 10 businesses fail” or “a business is likely to close after a year and a half of being open.” Studies show that half of new businesses are most likely to remain open pass the first year mark and into the four- or five-year territory, with about one-third surviving 10 years or more. So even though it might seem unusual that Madiba is approaching its 20th anniversary, it isn’t simply a stroke of luck, it’s a statistically plausible occurrence. What’s rare is seeing a restaurant or business embodying Madiba’s specific mission and focus on its community. More often than not words like “love” and “community” and “family” are merely a marketing tool for businesses trying to differentiate themselves from a satiated industry, but seldom do these places live this truth and go above and beyond their role as providers of service.

Majida Soaries, a waitress who started working at Madiba this year after 10 years of bringing her dates to the restaurant, tells me that when former employee E-Boogie, who was crucial in helping her get the position, died recently, everyone rallied together for his funeral, cementing the reality for her that Madiba is more than just another late night shift, or another restaurant to review on Yelp—it’s a second home for those who walk through its door.

“The guy who told me they were hiring passed away like a month ago, and it was intense because he got me the job. He’s the reason why I’m here,” Soaries says. “But to see everyone come together here, and how Madiba paid for the funeral [and] have an open bar and paid for everything. I mean, burial, casket, everything. It’s family here.”

The plight of Madiba goes beyond the loss of another favorite local restaurant, though, because it speaks to how easy it is to mindlessly reap the benefits that such places offer until the well runs dry and those of us who can simply move on to another spot. But as for what is left for those who can’t afford—either financially or emotionally—to move on, it’s hard to know just what will soon be left for them in Brooklyn.

You might also like