Aged Against The Machine

I was a big believer in second chances long before I ever got one. F. Scott Fitzgerald once infamously said “There are no second acts in American lives,” but he was a raging alcoholic who wore his wing-like hair in a middle part, so maybe he was just projecting.

Most of my teenage years were spent doing regrettable things while regretting them in real time. Every day seemed to bring some new situation in dire need of a do-over, some kind of adjustable instant replay in which I wasn’t the one who broke the tire swing and landed in swamp water in front of my friends. When I was 27, though, I actually did get a do over—one that was 10 years in the making.

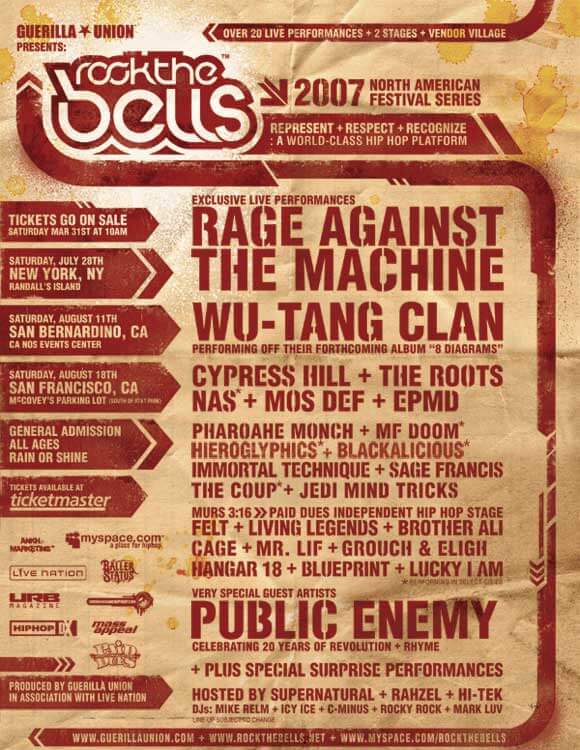

The original mistake involved a concert my friends and I went to in 1997. Not just any concert, but the most “1997” concert imaginable: Rage Against The Machine and Wu-Tang Clan. This double-bill was an almost scientific tableau of where I was as a 240-pound, 17-year old, straight, suburban, white guy. Rage Against The Machine was my shit. Any inherent contradictions about their anarchist, anti-corporate stance and the fact that they regularly appeared on TRL sailed right over my head. And Wu Tang was bombastic and fun and made esoteric references to old movies that I felt smart for catching. It was the show of a lifetime, and I couldn’t wait to go.

Actually, I couldn’t wait to have gone. Back then, I didn’t really love going to concerts, even though I went to them all the time. I was into the music, and I liked being out with my friends. But, I was stout like a barrel of pickle brine and not very tall. I always felt, at every second, like I was invading somebody’s personal space and leaving sweat deposits on their very existence. There was always a moment during every concert where I wished it would just end so we could go home. That was usually after, like, the third song. I would’ve rather impaled myself on a microphone stand than admit it at the time, though.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=w211KOQ5BMI

As sophisticated teens of discerning taste, it was important we not embark on a three-hour drive to the Coral Sky Amphitheater in West Palm Beach without first procuring the finest seed-encrusted ragweed money could buy. The only problem was, it was coming down to the wire. We spent most of the day waiting around for the one weed guy we knew in the greater Orlando area, who arrived so late we would’ve had to haul ass just to catch the opener. (Atari Teenage Riot. Ahoy, 1997!) The four of us filed into two cars with a half-ounce each, and hit the road.

Not a strong driver to begin with, I had the jitters even before getting us out of the garage. Throw in a bunch of really bad pot, the pressure to beat the clock, Enter The 36 Chambers at top volume, and it’s a wonder we didn’t crash into a ravine immediately. While I guided my 92 Nissan into what I hoped was the correct lane, panic rising in my stomach like garlic knots, my co-pilot Peter just kept rolling blunts and reacting to my driving with what could only be described as pre-traumatic stress disorder. My car was completely hotboxed when I saw through a plume of smoke that our friend Eric had pulled off the highway too early. He’d forgotten to gas up before we left. Now that he and the rest of us were high, though, this little detour somehow waylaid our mini-caravan from getting back to the highway. It should have been so easy. And yet this ungainly gaggle of stoned goobers couldn’t quite pull it off. Some of us had beepers, but nobody had a phone. We couldn’t communicate with each other, let alone Google Maps. We were hopeless.

When we finally did get to the amphitheater, we couldn’t tell whether the deafening crowd noise was due to the fact that nobody could wait any longer for Wu-Tang to storm the stage, or if it was the sated cheers of a crowd that had just had its faces rocked clean the fuck off. It turned out to be the latter. I imagined the members of Wu-Tang lighting that first post-show blunt on the tour bus as we walked in, soaking up the audience’s spent afterglow.

Adding insult to self-inflicted injury, our view for the remainder of the show was just terrible. Our tickets said General, which we thought meant Floor. But the layout was actually Floor, then a guarded concrete walkway, then a layer of seats, a buffer area, and then General—which was an elevated grassy knoll it would be pretty difficult to reach from the stage with a professionally chucked baseball. By the time Rage Against the Machine took the stage, looking like an adorable band of Jack Russell Terriers from our vantage, we were miserable. The night was a bust. We had concert-cockblocked ourselves.

We strolled back to our cars, defeated, our buzzes long since harshed. The prospect of more garbage-blunts did nothing to alleviate the reality that we were going to have to drive three more hours, all while stewing in the broth of regret. “Hey,” I said to Peter as we lit out for the highway, “There’s always next time.”

Except there wasn’t a next time.

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=H0kJLW2EwMg

Two years later, Rage Against the Machine put out their third album, Battle of Los Angeles. It was the first CD I ever had a burned copy of, and it could not have felt less special. I hadn’t paid for it and it didn’t have any cover art. This was the beginning of the digital era, which coincided with an era of me caring less about music and more about what the hell I was going to do with my life. The following year, the band broke up. They’d raged against the totality of the Clinton administration and somehow retired at the dawn of the George W. Bush regime—easily the most punk rock thing they ever did. Meanwhile, Wu-Tang wasn’t faring much better. The individual members flooded the market with really bad solo albums, then two group albums in two years, all without touring. In 2004, Ol Dirty Bastard died of an overdose. It was just a couple months after I moved to New York to begin the second act of my life.

With the Clan in decline, and Rage Against the Machine but a broken trail of Free Mumia stickers in abandoned high school lockers, things had completely changed for me. By 2007, I had lost a bunch of weight, kicked off my career as an editorial assistant at a publishing house, and moved in with my girlfriend in Spanish Harlem. Things were going resoundingly okay. And they were about to get better.

Rage Against the Machine reunited for Coachella that year, and soon afterward, the band was tipped to co-headline the Rock the Bells Festival in New York with—who else?—Wu-Tang Clan. I couldn’t believe it. Exactly ten years later, these two bands were back from the dead and playing together again—and in my backyard. It was as if Hailey’s Comet had soared by twice in my lifetime, carrying a second season of Freaks and Geeks in its marsupial comet-pouch. I immediately called up Eric, the friend from ten years before who I was still most in touch with.

If things had changed for me a lot in the intervening decade, they’d shifted for Eric at a tectonic level. He was now a married man and a father of two. He no longer got high and made mistakes. We spoke twice a year, tops, and I was fine with that. Talking to any friends from my past was a reminder that the past had even happened. Here, though, was a chance to actually correct a mistake from before, and Eric quickly agreed to fly out with his wife so we could correct it together.

The big day started with a foul omen. As we crossed the rainy threshold onto the muddy grounds of Randall’s Island, we had to surrender our umbrellas for safety reasons. Our finest bureaucracy-repelling arguments failed to make a dent, and so we reluctantly agreed that yes, we would hang out at this outdoor festival in the open rain all day, watching helplessly as our significant others’s teeth chattered in rhythm with “Bring Da Ruckus.”

If this was going to be that kind of day, Eric and I decided, we would have to get shit-wasted. The only problem was that we’d forgotten to stop at an ATM on the way. There were some kiosks on hand, but the fees were jacked up to Nevada strip club levels, which offended us on principle. We pooled our money together, and it was about $55. Eric proposed we spend it entirely on beer, no food. I got swept up in the moment and agreed, because the only thing more fun at the time than getting drunk was giving high-fives. My girlfriend, Sarah, and Eric’s wife, Lindsey, traded a certain look at this point, even though they were off to a rocky start.

The previous night, they’d gone on a getting-to-know-you outing and, according to Sarah, Lindsey had alternated between morose, horny, and incomprehensibly drunk for much of the night. Meanwhile, Eric and I had gone to the movies and ended up embroiled in deception. We were supposed to see the Adam Sandler gay panic extravaganza, I Now Pronounce You Chuck and Larry, but instead we saw The Simpsons Movie. Sarah had wanted us to see The Simpsons Movie together, since I loved the show and she wanted to be there for what could potentially be a special moment for me. Now I had to lie to her about the most boring thing a person could lie to his girlfriend about: pretending to have seen I Now Pronounce You Chuck And Larry, which proved shockingly easy.

The steady stream of beer had clearly begun to work its magic when, several hours in, Eric and I stole four umbrellas from the umbrella landfill near the entrance. Further evidence of the alcohol’s functionality included Eric yelling “Fla-vor Flaaaaav” louder than Flavor Flav himself during Public Enemy’s set. We were in rare form as Wu-Tang’s show time neared, so we excused ourselves to allow Sarah and Lindsey time to quietly tolerate each other as we got closer to the stage.

The stench of pot hung in the air all day like rainforest mist, but I had none with me. I desperately wanted to convince one of the openly toking children in the vicinity to get me high, but I was worried about how that might go. These kids were around the age I’d been at the show in 1997. Back then, I’d thought everybody was a cop. Any situation in which I smoked had seemed like it could potentially be the climax of an undercover operation set to entrap me, the unlikely fulcrum of the universe. If I wanted to get through to these kids, I had to talk to them on their level.

“If you let me hit that,” I said to one drenched, heavily tattooed teen holding an ornate glass pipe, “I promise I won’t drop it.” He shrugged, passed the pipe, and I happily hoovered it. Eric, who was already quite drunk and did not smoke pot, gave me a meaningful look as I inhaled. “Can my friend hit it too?” I asked, blowing a cumulus cloud of smoke like an angry dragon. The kid nodded and I passed the pipe to Eric.

By the time Wu-Tang took the stage, we were both baked and screaming. One of the things that had changed in the past 10 years was that I now loved going to concerts for the sake of going as much as for having been there. Though I was still a bundle of nerves about my body altogether, I finally realized there were equally gross bodies to be sandwiched up against at any given show, particularly this one. Between the vibe of the crowd around us, and our alcohol intake, we were having the time of our lives. As Method Man walked into the crowd on the hands of fans with an absence of modesty that might make Jesus Christ blush, Eric and I looked at each other and had a moment. We’d made it this time. Eric had a daughter who was nearly the age we were when we’d first met, Ol’ Dirty Bastard was dead, but for the time being it felt like we were 17 again, and that the future was unwritten.

It was only after Wu-Tang finished, though, that it finally sunk in how hungry and weak we were. All we’d had to eat over the last eight hours was a bite of Lindsey and Sarah’s chicken sandwiches—washed down with $55 of beer. We were running on fumes as we snaked our way through the crowd to get into the best possible field position for Rage Against The Machine, who were about to play only their second show since breaking up nearly a decade prior. When last we’d seen the band, we saw them from a cartoonishly distant viewpoint. This time, we were at the core of what any non-outdoor venue would call Floor. We were grout, essentially.

Somewhere during the murderous frenzy of applause as the band appeared, I realized we might be in trouble. Then the opening build-up in “Guerilla Radio” hit and all hell broke loose. Everybody lost their fucking minds. You couldn’t not jump up and down; so powerful was the crush of bodies pogoing all around you, that each person was jolted upward by proxy like a horrible human trampoline. Eric immediately went down, tangled up in a knotty thicket of legs. I scooped him up and slapped a protective arm around him until we were swept upward in a jumping scrum together. It was utter chaos. 20% of me was rocking out, 60% was engaged in self-preservation, and 30% was keeping Eric’s children un-orphaned.

After a couple songs worth of perpetual mayhem, the texts started rolling in. Lindsey was missing. Sarah was alone and having a bad time. I screamed into Eric’s ear that he had to go find his wife, and saw a flurry of emotions in response. I saw the 17-year-old Eric who couldn’t bear to miss this, and the 27-year-old provider who’d had a weird day and was relieved it was almost over. He left to go look for her exactly when “Bombtrack” kicked in and I took a flying elbow in the occipital lobe.

A few minutes later, I got a text from Eric that read simply, “We have to leave.” I was in no position to disagree. During the prophetically titled “Tire Me,” I made my way out of the madness to find the others. When Sarah and I caught up to Eric and Lindsey, Eric looked stricken. I didn’t asked in what state he’d found Lindsey, and I never will.

At the concert in 1997, we’d arrived too late, and at this one, we left too early. Nothing at all about how the day had gone, or about my relationship with Sarah, which ended a few months later, forced me to do an inventory about what other regrets I may have currently been living through without regretting them in real-time. I was just chuffed to have come as far as I had from being a 17-year-old overweight Milhouse. I never really thought much at the time about whether I could be going further.

The shuttle bus leaving Roosevelt Island was dank, muddy, and gross and, just like ten years before, it would take us hours to get home. But it was the only way.

This piece was originally written for the excellent Words & Guitars reading series. Follow Joe Berkowitz is New York-based a writer and comedian. Follow him Twitter.

You might also like