The 12 Best Books of 2015 that Didn’t Get Enough Attention

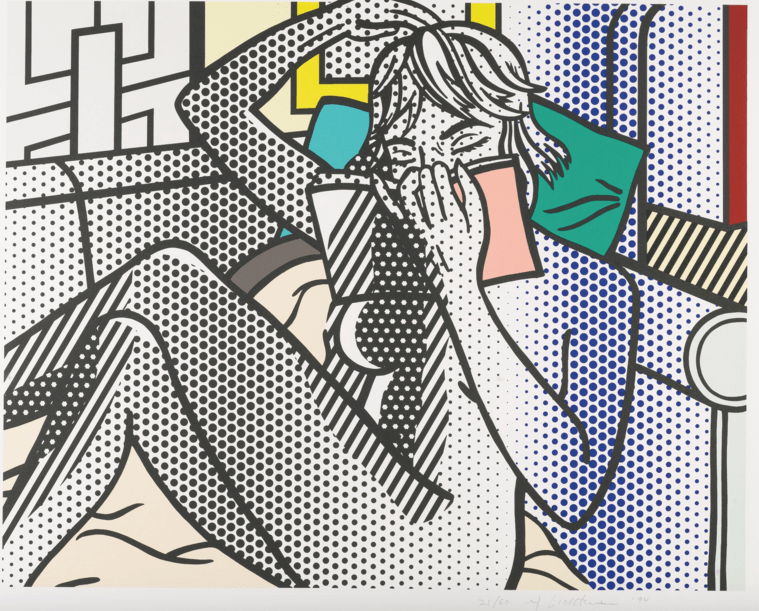

Nude Reading Roy Lichtenstein

Whenever we get to this time of year, marked, as it is, by reflection and reminiscences of the past 12 months, we always find ourselves thinking the same thing: At least there was good stuff to read. This annual realization is no small thing; we don’t take for granted that there is no such thing as a bad year for books. (And even if there were, we would happily spend a solid 365 days reading the best books of years past. So!) But anyway, we’ve spent a happy couple of weeks reading all the Best Books of 2015 lists from various other publications (and then, you know, having them ranked) and have been happy to see many of our favorite books of the year (chief among them: Paul Beatty’s The Sellout, Ta-Nehisi Coates’s Between the World and Me, Lucia Berlin’s A Manual for Cleaning Women: Selected Stories, Alexandra Kleeman’s You Too Can Have a Body Like Mine) making out like fucking bandits right now. Great writers getting much-deserved attention—what could be better? Literally nothing.

But also: Lists are exclusionary by nature and while we are very much in favor of being judgmental in pretty much every area of our lives, we also can’t help but feel every year like there are untold numbers of books which get ignored in favor of other options for reasons as varied as better publicity campaigns or the power of critical-bandwagons or more favorable release dates, etc. And while we can’t just list every single book that maybe didn’t get its year-end-list-due, we can list our top picks for what need even more love than they’ve gotten so far. Here, then, are the 12 books we really really loved this year that we think you should all read, like, right now.

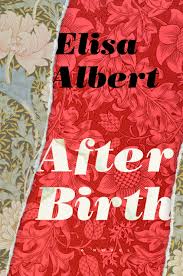

After Birth Elisa Albert

In reviewing After Birth for the New York Times, author Merritt Tierce predicted that the novel would “no doubt… be shunted into one of the lesser subcanons of contemporary literature, like ‘women’s fiction,'” though it ought, Tierce continued, be considered “as essential as The Red Badge of Courage.” Which is exactly right, of course: Albert’s novel is an unflinching look at the trials and tribulations of new motherhood, yes, but also the realities of being a woman and the attendant never-ending quest to find a place in a society that doesn’t want to make room for us on our own terms and it is as much a story of heroism and personal maturation as is Crane’s classic. It is easily one of the best books of this year, and, really, any other.

Hall of Small Mammals Thomas Pierce

Pierce’s debut collection of short stories came out at the very beginning of 2015, a time which seems like it existed in a different world entirely. But then again, Pierce’s stories too seem like they begin in a different world entirely, or, as the author himself described it, as existing in “a universe a few inches to the left of this one, perhaps.” But that’s all the more reason to seek out the beautifully strange characters and settings that make up these stories, all of which and whom are actually more familiar than Pierce might have you believe, but none of which or whom will leave your consciousness for quite some time after you’ve read about them, leaving you to wonder if you too now exist in that universe just a few degrees of from our own, and how that’s actually just fine.

The Small Backs of Children Lidia Yuknavitch

What do you get when death and sex and violence and love and terror and ecstasy are all combined in the most visceral and explosive way imaginable? You get art; you get life. You also get this novel, which will, in the most elemental and yet also elevated manner possible fuck you. Yuknavitch insinuates herself into your very core with Small Backs with a fierceness that had us gasping out loud at several points, tempted to throw the book down, feeling like the words were actually burning into me. The uncompromising, relentless nature of Yuknavitch’s story-telling can be difficult to handle at times, but isn’t that the case with almost all art? And any life worth living?

How to Be Drawn Terrance Hayes

There are readers who will devour pretty much anything put in front of them, but still shrink at the mere sight of a book of poems. Hopefully, 2015 was the year that changed for them, perhaps aided by the release of Claudia Rankine’s powerful Citizen late last year, because Terrance Hayes’s How to Be Drawn is not to be missed. In it, Hayes experiments with poetic form (verse in a spreadsheet? why not) and stuns with his poetic innovation, leaving us in awe, with a promise to ourselves to read more poetry.

Beauty Is a Wound Eka Kurniawan

While actually released in 2002, young, Indonesian author Kurniawan’s novel only came out in English this year, but is such a powerful sprawling work, which deals with issues both global and personal that it deserves every possible accolade out there. Or, as we wrote in our review of it in October:

It’s an astonishing, polyphonic epic, a melange of satire, grotesquerie, and allegory that incorporates everything from world history to local folk talks. In style, it owes something to the magical realism of Gabriel Garcia Márquez and Salman Rushdie; in structure and ambition, it recalls Günter Grass’s The Tin Drum, another novel that foregrounds a picaresque narrative against the dense churn of history—in that case, Europe during and after World War II—as a way to understand that history’s effects on a place and its people.

Read it.

Negroland: A Memoir Margo Jefferson

Former New York Times critic Margo Jefferson reveals what it was like to inhabit the world of Chicago’s black elite in this fascinating memoir. Jefferson calls this world “Negroland” and she explains that it is her moniker for the “small region of Negro America where residents were sheltered by a certain amount of privilege and plenty.” And while “privilege” is one of the most loaded words around these days, carrying with it, as it does, connotations of obliviousness, Jefferson ably navigate these waters as she demonstrates that despite the advantageous upbringing she was afforded, as a black woman, she never took that level of “privilege and plenty” for granted, never let it stagnate into mere entitlement.

Infinite Home Kathleen Alcott

In her second novel, Alcott creates an entire world within the confines of a Brooklyn brownstone; it’s a spectacular feat, and one that could veer into preciousness in the hands of a less able artist. Each character has his or her own personal demons (some, like one woman’s son is about as true a Brooklyn bad guy as can be imagined: a finance guy who wants to score big on a real estate deal) but the manner in which they all support one another is at once totally recognizable and yet also a look at the best possible version of what can happen in this city of ours, as we all live—literally—on top of one another. If you can get through this without crying, well, you are a stronger, much less feeling person that we are.

Welcome to Braggsville T. Geronimo Johnson

We genuinely hate to say: If you liked ____, then you’ll love ____. But here we go, in case you need some convincing: If you liked The Sellout, then you’ll love Welcome to Braggsville. (Oh, and if you didn’t like The Sellout? Get off this site. You have no place here.) Johnson’s novel about four well-meaning Berkeley students who descend on Braggsville, a small, still-segregated Georgia town, in order to stage a protest during one of the town’s reenactments of a Civil War Battle, is satire of the sharpest sort and effectively upends each and every one of the stereotypes with which we’re all familiar. Nobody is safe from Johnson’s brilliant words, and while the end result can be an at times unsettling look at our society and its many, many flaws, it is also a wholly necessary one.

Barbarian Days: A Surfing Life William Finnegan

We were first introduced to this book via an excerpt in The New Yorker and were so completely swept up and away by Finnegan’s spare, masterful prose that we couldn’t wait to see if the novel would help us stay on this particular wave a little bit longer. Luckily for us, Barbarian Days didn’t disappoint; Finnegan takes readers on his long, strange, lifetime trip riding waves around the world, first in California and Hawaii as a child in the tumultuous 60s and then throughout the world. The book serves not only as a surfing memoir, but also as a classic road trip story… only these roads are paved in water, and can come crashing down at any time.

Night at the Fiestas Kirstin Valdez Quade

Here’s another book we were also introduced to via the the New Yorker (that subscription really just pays for itself, you know? not in, like, money, but in good books) when we first read the excellent “Ordinary Sins,” a story about a young, unmarried pregnant woman working in a Catholic church and her attendant guilt due to her compromised situation. That story is in this collection and is one of many true masterpieces within it, many exploring the way our sense of self—and the shame that so often resides within it—can cripple us, and blind us to the beauty around and, most importantly, within us.

In the Country: Stories Mia Alvar

In this collection of stories (and, yes, there are several collections of stories here, because they rarely get the attention they deserve), Mia Alvar reveals a world of fluid borders—both international and ethical. Her characters crisscross the globe, going back and forth from the Philippines to the United States and the Middle East, all the while leaving morally complicated trails in their wakes. Alvar deals beautifully with issues of identity and allegiance, and the novella which ends this collection is a quiet tour de force about the turmoil intrinsic to not only the characters’ lives, but also to the country—the Philippines—they call home.

Loving Day Mat Johnson

Here, Johnson—author of Pym and graphic novel Incognegro—offers a darkly comic look at race and what it means to be mixed-race (Johnson has called this novel his “coming out as a mulatto,” and the narrator calls himself “a racial optical illusion”) via a narrative which revolves around a falling-apart Philadelphia mansion and is told through the singular, mordantly witty voice of one Warren Duffy, whose traumatic story isn’t just his own, but is rather America’s own.

Follow Kristin Iversen on twitter @kmiversen

You might also like