Back to the Future with Marjorie Prime, But Is It Worth the Trip?

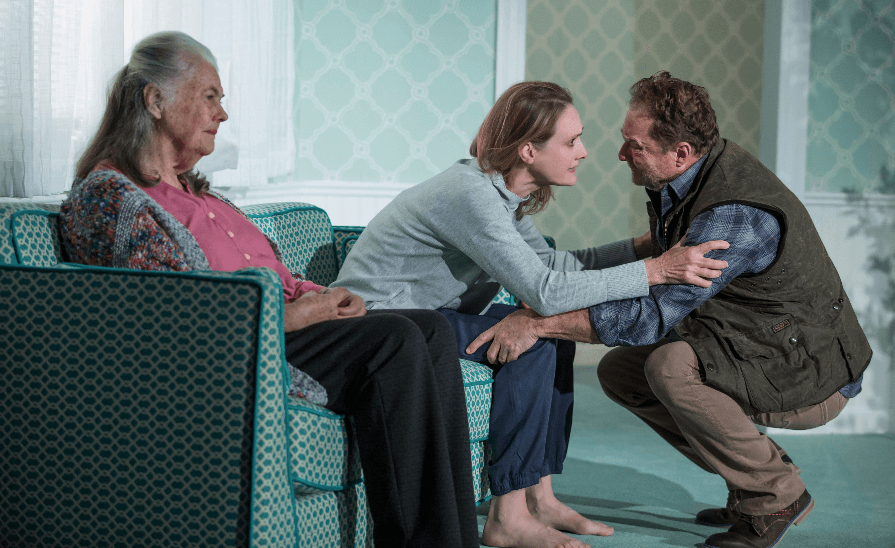

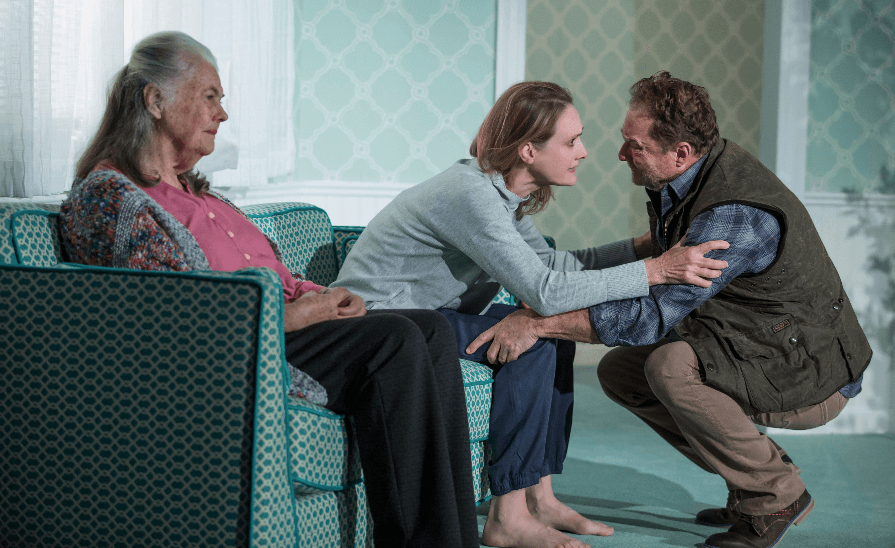

photo by Jeremy Daniel

MARJORIE PRIME

Playwrights Horizons

108 E. 15th Street

There’s the start of an interesting idea in Jordan Harrison’s play Marjorie Prime, which has a vaguely futuristic sort of premise, but it never comes to fruition. The action takes place in a setting designed by Laura Jellinek that looks partly like a hospital waiting room in some warm weather location and partly like a brand new assisted living apartment; there are would-be soothing yet forbidding light green patterns in the decor that subtly clash with each other. Marjorie, played by Lois Smith in her best stripped-down style, is an 85-year-old woman whose mind has started to go. Her daughter Tess (Lisa Emery) has provided Marjorie with a living facsimile of her dead husband Walter (Noah Bean) as he was when he was 30 years old.

The first scene Walter and Marjorie have is a conversation where he reminds her of things she’d like to remember, things that might give her pleasure, but the memories he feeds her seem malleable, subject to the whim of re-writing. We can never be sure what exactly happened in the lives of Marjorie and Walter because Marjorie herself is unsure now and given to wishful thinking, but this conceit is blurred because of numerous faults in the writing. The characters of Marjorie, Tess, and Tess’s husband Jon (Stephen Root) feel like an accumulation of arbitrary details rather than characters we can believe in. And so when Harrison begins to take those character details away from us as the play goes on and these people are replaced by hologram versions of themselves, it has no impact because we cannot feel the loss of people who haven’t been convincingly characterized to begin with.

Smith, who recently did this play in Los Angeles and also just filmed it for director Michael Almereyda, gives this material her full radiant attention, but it is painful to see her beautifully committed work buried under cute old lady jokes (surely we could have done without Marjorie singing bits of Beyonce’s “Single Ladies,” even if Marjorie was supposed to have been born in 1977). The revelation of what happened to Marjorie’s son carries an unfortunate echo of Beth Henley’s Crimes of the Heart, and there are many times here where the dialogue falls into arch patterns that feel more like Harrison’s random thoughts than anything else. He only scratches the surface of his theme and his characters, so that Marjorie is merely vain and Tess is mainly a daughter worried about her mother and their relationship. Nothing is fleshed out, and so it is impossible to be moved by the absence portrayed during the last scene of the play because that absence has been present, unfortunately, all along.

You might also like