A Gentrification Thriller for Our Times: Talking to Fort Greene’s Sebastián Silva about Nasty Baby

This is the second time you’ve worked from a treatment. Crystal Fairy came together in an improvised fashion while you were in Chile waiting for funding for Magic Magic, and I was curious if that experience informed your similar process on Nasty Baby.

For Nasty Baby, there was an outline, around 23-25 pages. It was organized; the only thing we were missing was the dialogue, and I had some dialogue ideas written. “Then Polly says this, then Freddy does that.”

I’ve always said that improvisation is a myth. I’ve never done a mumblecore movie, so I don’t know how those go, but Crystal Fairy and Nasty Baby are both movies that have a structural arc that was very thought out. The second and third acts of Nasty Baby were very much planned. They are improvised when it comes to dialogue, but it becomes a scripted project once you’ve done the third take. Everybody knows what they’re saying, and you just have them repeat it over and over again.

In terms of working with the actors, do you feel like your approach to directing a treatment is different than directing with a script? Both Crystal Fairy and Nasty Baby are semi-autobiographical, did that help shape your conception?

Sure. For Nasty Baby, we shot in my apartment. I’ve been in my dining room with friends, and I know how people move around the space and what the dynamics are. If someone rings the doorbell, I always run downstairs. How do you interact with the cat? Little things like that are natural, you’re just doing what you’ve always done.

When you have a full-length screenplay and you’re following dialogue, it’s not as stressful. Improvising, you are always having fun, but you’re always on edge. You are making decisions on the spot, like, “No, fuck this location, let’s go next door.” You’re so present that you can modify your movie however you want. Nothing is written. Nobody is expecting anything. Producers are not going to ask, “Where the fuck is this part?” because we all agreed that we were going to improvise.

When you’re doing a screenplay that’s fully written, you’re sitting back and scratching things out. “He said that, we got it, that’s perfect, we already shot the stretch where they walk from one place to the other.” It’s more relaxing because you are following a guide and you’re feeling things get done. If you follow that guide, you’ll have a movie. You could give a screenplay to a bunch of robots, and they will make your movie. If you give an outline to a bunch of robots, they will come up with some weird shit.

When you shoot something that’s improvised, do you feel like that decision dictates the cinematography?

The DP Sergio Armstrong came to Brooklyn a week before we shot and we went and looked at the locations. We plotted a little bit and figured out the coverage, but because the dialogue is improvised, it doesn’t really affect the cinematography directly. We’re never setting up lights, so that gives us a lot of time. We establish how we’re going to shoot the scene before the first rehearsal. We figure out where the cameraman is going to be standing, but then it does get crazy when I grab the camera. Let’s say I want Kristen to roll her eyes once, so after the take, I’ll be like, “Nobody move, we’re not cutting. Kristen, I’m gonna get on your face and run the scenes from two beats before and roll your eyes.” And then we do it again and again and then I’m done.

The DP doesn’t mind when you do that?

He better not! [Laughs.] We’re really good friends, and I tend to like to work with people who are not very precious. I can see some DPs freaking the fuck out, though.

How did the cast come together? Did you always have Tunde and Kristen in mind?

I met Kristen and Tunde through Alia [Shawkat]. In the beginning, as weird as it sounds, Polly was going to be played by Katie Holmes.

It would be a different movie, but I could kind of see it.

She sort of abandoned the project at the last minute. She stopped replying to emails. It was very mysterious.

Maybe the Scientologists got her. So Alia was already cast?

I wrote the part of Wendy for Alia just so we could be together onscreen and work on a project. We’re really close friends, and I wanted to work with her. Wendy wasn’t part of the movie and then we were shooting the shit and I said, “You should totally be in Nasty Baby.” So she came on board and I had a burger with her and Tunde. We kicked it immediately, and I said, “You’re hired.” I didn’t even know if he could act or anything. I usually don’t audition people. I like to get together with them and see if we click. If I sit down with someone and have a burger or a beer and we have a good time, it’s kind of a no brainer. Kristen, I didn’t know who she was.

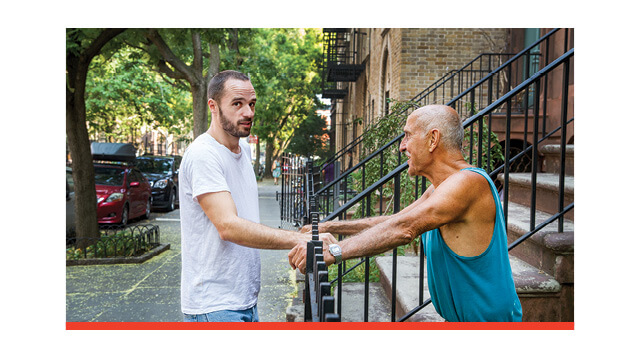

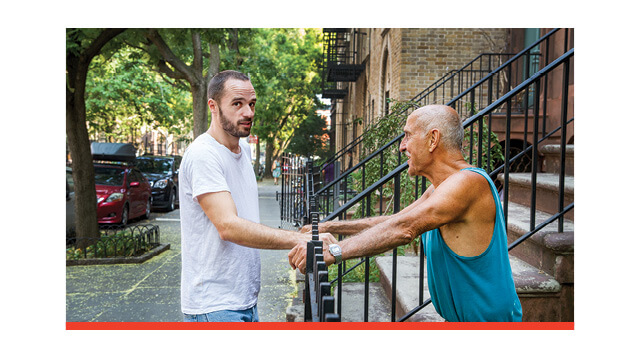

“I feel that Fort Greene is almost the best place

to depict a gentrification thriller;

it’s still a little mixed, but it’s really fading.”

Really?

I don’t know anyone. I didn’t know who she was, and Alia told me, “I have a friend, Kristen. Look her up and see if you like her.” And then I looked at her videos and saw that she was a genius. And I was like, “Please get her!” So Alia got us on the phone and we started laughing immediately. I was like, “You’re hired.” We met in New York for some kind of premiere she had, and we became close friends really quickly.

You mentioned you shot it at your house. Did you always know you wanted to set it in Fort Greene?

Pretty much, because it was easier. I think I always knew I was going to play Freddy. Nasty Baby was similar to Crystal Fairy in that I wanted to make a movie while I was waiting for funding for another. It was casual. So I was like, “Yeah, I’ll be in it.” And I wasn’t going to play anything but myself, so it just made sense for the character that he had a lot of shit that I was going through. I’m 36 and I have a lot of friends who are trying to have babies. I paint a lot. I’ve never been into the art world, but I know about it. I had the idea for a silly Nasty Baby performance back in the day, and I thought it would be fun to bring it together with being a dad. The compulsion of parenthood with being an artist. The leaf blower was a guy across the street who I wanted to kill every morning. Nasty Baby doesn’t have an intriguing storyline—it feels more like a lifestyle and then an abrupt change.

You shot in Fort Greene because it made sense for the character and because it was at your disposal, but I also think it’s an important setting with respect to the Bishop because Fort Greene, of course, is an area that’s been gentrified. There are definite racial overtones when you have a mentally ill black man harassing an upper-middle-class, white, female doctor.

Absolutely. That is a huge part of why I shot it there. They are going after a black man who is in his own area. It is the peak of gentrification; it’s the extreme of it—going after someone who is breaking the harmony of what the gentrifiers have built. I feel that Fort Greene is almost the best place to depict a gentrification thriller; it’s still a little mixed, but it’s really fading. Williamsburg is a little bit different.

I read an interview where you talked about how TIFF rejected the film because of the ending.

I wonder if I’m going to get sued by them. I should ask my producers for the email. It was along the lines of, “We like the movie, but not the third act. Could you do something about it?” And I was like, “That is the movie. How could you ask that?” I would have never made the movie if it didn’t have that third act. They wanted like a mumblecore, cutesy movie in Brooklyn with Kristen Wiig instead of the movie that it actually is. I’m going to ask my producer for that email in case I get sued by Toronto for defamation, and then I can be like, “No. Here.”

Cannes apparently does that all the time, in terms of relegating films from the Main Competition to Un Certain Regard or Director’s Fortnight. Force Majeure, which I thought was amazing—

My favorite movie of the year.

It wasn’t in competition because they thought the scene where the guy breaks down and cries was too over the top, and Ruben Östlund refused to cut it.

I love that scene.

I know that the Bishop factors into things early on, but it does feel like Nasty Baby is going in one direction and subversively veers into another. A lot of that is playing with the audience’s expectations of what we think a movie will turn out to be when it presents this concept of “new domesticity.”

Well, for me, the movie clearly has two story lines, so it’s weird that you wouldn’t expect them to come together. After the last confrontation with the Bishop, they take off to Mo’s parents house, and there’s a long stretch where the film centers on the baby subject, but then there are little reminders of the Bishop. We keep distracting the audience with Freddy and his art, and people forget about the Bishop. But for the first 45 minutes of the movie, he’s huge. He’s the antagonist. I’m not going to deny that it’s a very manipulative turn. The way I treat the film is different. There’s score all of a sudden, for the first time in the film. But I feel that it’s a payoff for people who were concentrating on the film, and paying attention to that storyline, because we did promise something there.

I think that’s it for me, unless there’s anything else Brooklyn Magazine needs to know.

The only thing I can think of is that the roller rink where we shot the scene over the end credits is closed now. It’s really sad. It was called Crazy Legs and was held in a high school gym in Bed-Stuy. Look it up. ♦

You might also like