Cleopatra’s Shadows: Talking to Emily Holleman about Her Debut Novel, Feminism, and Younger Sisters

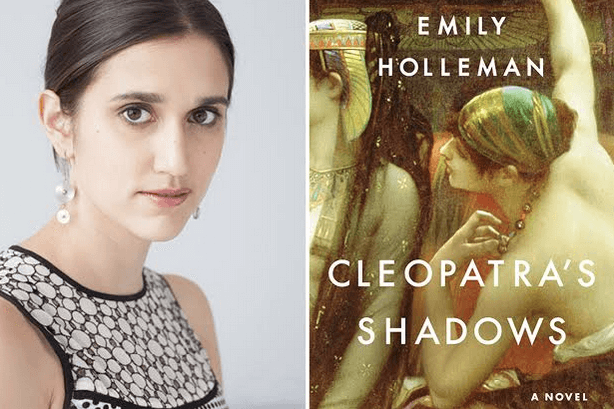

Emily Holleman and her novel Cleopatra’s Shadows

After several years as an editor for Salon, Brooklyn writer Emily Holleman made the decision to take a risky leap of pursue her passion: During a fateful trip to Egypt, Holleman first discovered Arsinoë, the younger sister of Cleopatra, and the very inspiration for her book series. Utilising her lifelong love of the ancient world and her newfound appreciation for Arsinoë, Holleman wrote her first work of historical fiction: Cleopatra’s Shadows. The novel follows two young, steadfast sisters, Arsinoe and Berenice, as they navigate the precarious power hierarchies in place at the bitter end of the Ptolemy’s Dynasty. Previously relegated to footnotes, these women now take center stage and have us asking the question: Why does Cleopatra get all the attention?

In her novel, Holleman brings Alexandria to beautiful, spirited and, at times, tragic, life. Her characterization of these women reaches the reader as familiar and nuanced, in spite of their marked absence from any ancient historical canons. Ultimately, Cleopatra’s Shadows attempts to fill in the large gaps written history has left for us, and leaving us to think more about the importance of Arsinoë and Berenice as formidable precursors to the famed reign of Cleopatra. We spoke with Holleman recently about her novel, and about how even though history really does tell the tale of the victors, maybe fiction can make up for that.

The first thing I wanted to talk to about was the transition from Salon to the road less traveled… writing a historical fiction novel. What propelled you to do this?

I’ve always wanted to write fiction on some level. So a lot of the decision to leave Salon was sort of a reckoning when I was—I guess I was 26—when I decided to leave. I thought that if I’m going to make a big scary decision, why not make this now, as opposed to in five years or ten years. So part of it is where you are in your life and after you’ve gone through the first couple of scary post-graduation years….

I’m so glad that you went with passion over money! No one’s doing that anymore. I read something from the end of the book about how you had to babysit to make ends meet, which is kind of where I’m—where a lot of us are at—right now.

Yeah, yeah, and it’s not easy. It’s not the easiest thing to do. But it was one of those things where I was like “Well, I just have to support myself. I don’t have kids yet or anything like that.” But I guess part of it was that even though I loved working at Salon in a lot of ways and I loved the people that I worked with and I think it does a lot of important stuff, but working on the Internet can be very… I mean dealing with the constant, sort of, barrage of change… the complete lack of focus or attention on any one thing for more than like a second, can be really frustrating.

So there’s definitely the feeling that I wanted to write something that doesn’t feel so fleeting. And obviously you can do that with a lot of time periods, you can do that contemporaneously as well, but I think that part of it was I wanted to escape into something that has an incredible number of modern echoes, and feminism, which is definitely a large underpinning of the role of women and how women negotiate their roles in different societies and times and cultures, is usually important. But also move into something where it didn’t feel like everything just had a split second of attention given to it.

So about this feminism aspect. When I was reading, that felt to me to be the most politically relevant part to contemporary America. And given your political background—

I don’t know; I hate feminism. I’m totally not left wing. (Laughter) Yeah, you know, everyone that’s worked at Salon.com, that’s not a thing. (Laughter)

Feminism is something I’m always looking to promote. It would make for a very boring book about two women if you didn’t deal with the fact that they are women and that they are trying to deal with the power structure and hierarchies in the society within which they live. I don’t know how you would write a story about two women that was interesting that was just about getting married and falling in love, and not in some ways interacting with feminism.

I don’t even want to get into the issue of feminism as a potential “bad thing”; what I would say is that women struggling for power is going to address feminist issues.

You mention that Arsinoë was confined to footnotes before this book.

I mean, pretty much. Arsinoë gets mentioned at the end of Caesar’s Civil Wars, which Caesar actually wrote, and then by her name at the beginning of the Alexandrian War which probably Opius, one of Caesar’s generals, wrote. But that’s much later than all of the stuff that’s going on here; also stuff that I’m sort of tackling right now in the second book. But beyond that, Arsinoë certainly doesn’t appear hardly at all. I mean she isn’t named, neither she nor Cleopatra nor Berenice—actually I guess Berenice is named later on by Stabo, as one of the daughters—but that’s about it. In terms of ancient sources, I think Caesar probably mentioned her the most, but that’s all when she’s a teenager at the time when Caesar’s back in Rome.

“Younger and Elder,” you split the book up that way, by narrative of Arsinoë and Berenice. I think my understanding was that you sort of took more of an interest in Arsinoë’s character.

My initial idea of the whole series was to write Arsinoë’s story, so… obviously from that whole perspective I am coming in that as a fellow younger sister, as someone who understands that role, and that feeling of being overshadowed. It was sort of interesting, and I didn’t even know when I started working on this how I was going to write it. I thought it was going to be one book. I didn’t realize it was going to become four books. The more I wrote from Berenice’s perspective, the more I became super fascinated by her. And it think it became this sort of interesting thing where I thought I was really telling Arsinoë’s story, and then I realized that this particular book, the first book, is in many ways (in terms of plot and character arc, maybe even in more ways) is Berenice’s story.

I know you spent a lot of time in Brooklyn Public Libraries, and you were very careful about the perspective that you wanted, and that Romans provided the majority of the perspective(s) in which these histories were written. I was wondering, did you consult anyone on how to write this, did you try to write it as sort of a classical epic, because I know you said this story reminded you a lot of a Greek tragedy.

Oh, I mean, the whole cycle reminds me of Greek tragedy… Almost anything you write about the past is going to be tragic, especially writing about the Ptolemies, because it doesn’t end well. And especially because you’re fighting against what we now know to be the inexorable rise of Rome and that even at that point people accepted that Rome had won. I mean, Rome had conquered just about everything except for Egypt at this point. And so there’s something inherently tragic as having Berenice as the heroine struggling against that when you know, assuming one has knowledge of ancient history, that the Ptolemy’s aren’t going to rise again. This is the bitter, bitter end… This is something that’s fascinated me since I was a kid; how relevant how some of these stories still are; how we look at the Illiad and the Odyssey, and these tragedies are still used. We talk about the Kennedys as this tragic family in the same way—and maybe this is a horrible thing to say—but in the same way that we talk about the guy who served his nephew to eat for dinner, I’m blanking on the name… anyway, we still talk about them as like “the cursed house,” (an idea that’s very Greek) and we still talk about politics and all these dynastic families in the same way.

I liked how you weaved in the education aspect in creating the narrative; you largely used Arsinoë’s education as the way she came to terms with what was happening to her. And I assume that’s what people were definitely reading and studying, especially someone as well educated as her. Was this something you had in mind? Was she necessarily as precocious as she came across?

Well, it’s an interesting thing. It’s an interesting thing writing from a child’s perspective in general, and especially a child from a completely different culture. Because our ideas of childhood, and when people are responsible enough to do certain things and understand certain things are very recent in a lot of ways. I have a lot of nieces and nephews. They’re all nine and under. And they’re wonderful, but they would not interact with the world, they would never interact with the world, nor would I at that age, in the way that Arsinoë does. But I think a lot of that has the idea of childhood in the 19th century as this incredibly precocious and innocent time, and children were seen, not fully, but largely as miniature adults who needed to be trained and prepared for these steps. So, I think it would be almost impossible to compare. I mean, would Arsinoë necessarily be that precocious? Maybe, maybe not. But it’s not really comparable to the way we treat children in our society. That was life.

Would you hope that this story would be something that’s introduced into the classroom, maybe even into college classrooms?

I mean, yeah. I would love that. I would love for people to read the book in any and all environments. Obviously, you know, it is fiction. But I really think it also gives a sense of what living during that time period is like. I mean, it’s impossible to know how people thought then. But I hope so. I hope that people would find that useful.

I’m curious about your future plans. I know you’re planning on continuing the saga.

(Laughs) Yes, I’m continuing the saga.

I don’t know if you’re planning, then, on replacing Berenice’s narrative with another person, or changing the form of the book…

Well, the form of the book—I think I can say this—

Am I prying?

Oh! I feel very offended! No, no, I think I can safely say since I sent in a synopsis of book two and since I have written most of book two, that book two will feature the younger brother Ptolemy as the second narration. He’s closest to Arsinoë in age, he’s five years younger.

And they’re all named Ptolemy too!

Oh my—I cannot tell you how frustrating it is that they’re all named Ptolemy. I call the other one Ptolemerian, which is just the Greek nickname for “Little Ptolemy.” Otherwise, I mean otherwise I was like “I’m going to have a book where everyone is named Ptolemy and no one is going to know what I’m talking about.”

There are elements of dreams and premonitions that are central to this story, a sort of mythical aspect, and I was wondering whether this was an element of education at that time, or whether you wanted this story to have a more magical ambiance to it.

Well, I think that the world had a more magical aspect to it in the ancient world. What’s really fascinating is that when you’re reading these ancient histories, which I’ve obviously done… a lot of… but if you’re reading like Athien or Dio Cassius or any of these guys, they’ll be writing this pretty dry history and then they’ll say something like “and then Caesar had this dream,” and then they’ll record the dream, and then “Caesar saw the ghost of so and so,” and then they’ll explain how that happened, like in his dream, and what that meant. It’s given almost equal weight as history, and I find that fascinating. Even if people didn’t believe in them, these are smart guys who are writing about history, and whose work we rely on. So obviously it reflects some sort of status of the way they used to think.

Would you be interested in the future potentially writing about some other marginalized female characters we wouldn’t otherwise know about—whether that’s a theme you’d continue to work on. Because that seemed to be your inspiration for this book. Are there any other character’s in history like this?

I’ve thought some about it. Right now, it’s hard for me to really imagine what’s coming next. I would sort of think about Nefertiti and Akhenaten’s daughters. They had these four of five daughters—

Is that King Tut’s father? He had like a weird elongated skull I think. I was just a watching a special about how King Tut and his father basically looked like mutants, and how King Tut had a slew of genetic diseases.

I mean the whole thing is totally weird. They created this whole new religion, and banned all the old religion, so then Tut took over and possibly married one of these daughters before he died young. Everything went back to the old ways. So I’m thinking about that transition and what the lives of these women were like. So, yeah, that would be something I’ve thought about, but I’m not fully, fully sure.

That also rides along with the incest that plagues the House of Ptolemy.

Absolutely.

Often times, on my rooftop (which I can’t afford), I see Manhattan, and sometimes I think, you know, this is as close to a modern day empire as I’ve ever understood the word—so I was wondering if that’s affected you in any way or helped you, the bustling of our city, with creating some of the images in your book.

I definitely would say it has. I mean, Alexandria was in decline in a lot of ways by the time I’m writing about it, I mean not fully, but certainly not at its zenith at around 200BC But, it was definitely a HUGE bustling city, and it was certainly much more beautiful than Rome was. I guess later on Rome got a little bit snazzier. But when Cleopatra went to Rome, she was surely appalled by the brick everywhere, no marble, everything looked like crap. So I definitely think being in a city, especially one where a lot of people think what they’re doing is important, and who are doing important things. And also this mentality of being the center of the world, which I think Alexandria definitely had, even if it wasn’t necessarily deserving of that reputation.

New York is sometimes a little bit kind of like that now I’d say.

Yeah, exactly. And there’s also this idea too of the decline of the American Empire and all the craziness and things that people say and do.

Is it the END of New York? Is New York OVER?!

(Laughs) This is the end of New York! You know, we look at the 70s. The intense nostalgia that everybody feels that is… the human condition is to feel nostalgic about what came before, what you missed.

You might also like