Strange Ways: The Long Journey of Howard Fishman

All photos by Matt Licari

Typically, you start at the beginning, but in the career of Howard Fishman—the songwriter, bandleader, playwright, composer, and amateur musicologist—there are so many beginnings that they begin to blur into something else entirely. Fishman has decamped to New Orleans with $300 in his pocket, a guitar, and a little suitcase. He has opened and then closed an avant-garde theater company in Poughkeepsie. He has recorded an album about hitchhiking through Romania, composed an oratorio that meditates on the frontier tragedy of the Donner Party, busked at the Bedford Avenue subway stop—in the 90s—and formulated a project entirely around Bob Dylan and the Band’s Basement Tapes. A whole lifetime of embarking on new endeavors that have little in common save that they found themselves in the crosshairs of Fishman’s penetrative curiosity, all undertaken while resisting overtures from labels and would-be managers to pick one path and stick to it. His discography is steeped in country, soul, gospel, rock, blues, Dixieland jazz, Gypsy swing, and American folk. It reads like the life’s work of several, only vaguely similar musicians.

Now, with his eleventh and latest record, Fishman is looking back—at least as much as he ever does. Uncollected Stories is a compilation of previously recorded outtakes, live performances, standards, and covers; it’s the first Howard Fishman record that doesn’t feel like an emotional dispatch from the throes of an obsession. Maybe, then, it acts as a compendium of his career, which I can only really describe as a long and willful self-guided tour that crosses paths with traditional notions of success, when it does, only at random. Not that Fishman hasn’t given everything to his music, because he has.

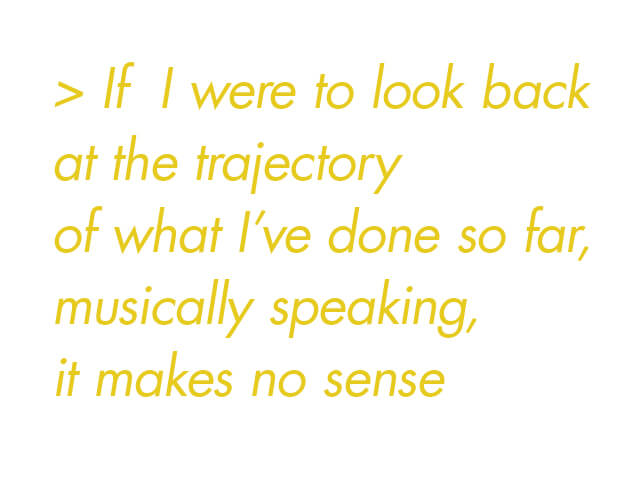

So let’s begin at what is, for this story’s purposes, the end. “If I were to look back at the trajectory of what I’ve done so far, musically speaking, it makes no sense,” Fishman wrote to me in an email following our final interview. We were in Helsinki, and it was the night after Fishman and The Biting Fish, his New Orleans-style brass band, had concluded a three-night mini-residency at the downtown jazz club Storyville. “I have not done what one is supposed to do if one wants to make it in the music biz, and yet I can look back at the last 15 or so years and feel a sense of satisfaction that I created a modest body of work and pursued things that have interested me each step of the way, without having to account to anyone.”

He added: “I’ve been able to sort of piece together what from the outside probably looks like a somewhat chaotic artistic existence, but to me just feels fun and exciting and absolutely never boring.”

The beginnings of Howard Fishman, the person, are easier to explain. He was born in 1970, in Connecticut, and grew up in a household of music—his father was a virtuosic classical violinist, and Fishman and his younger brother studied violin, trombone, and piano. At age 12, he was cast in a semi-professional production of Eugene O’Neill’s Ah, Wilderness! in Hartford. The experience sparked an abiding interest in theater that runs as a sort of counterpoint to Fishman’s musical career, occasionally intersecting in musical-theater projects like his Donner Party opus, We Are Destroyed, and A Star Has Burnt My Eye, an autobiographical play about his love for the work of the obscure 50s folk musician Connie Converse, which had a run at the Brick Theatre earlier this year.

During his college years at Vassar, Fishman spent more time doing theater than playing music. It wasn’t his major, though—the requirements were too senselessly demanding. Instead, Fishman formed his own rogue company, comprised of friends who “were a bunch of drunks and ne’er-do-wells,” who staged site-specific productions sans the imprimatur of the college’s drama department. Their first was an adaptation of O’Neill’s The Iceman Cometh, a play that concludes with (spoiler alert) one character committing suicide, and another wishing for death’s embrace. The performance was five hours, held during an underground bar’s daytime off-hours. Despite this, it was a huge success with the Vassar crowd.

Fishman and his ragtag group, calling themselves the American Theatre Company, continued staging plays at non-traditional venues around Poughkeepsie, and after graduation, they rented a storefront HQ on Main Street. But once the project left the confines of campus and became dependent on patronage from the Poughkeepsie community rather than students at Vassar, it didn’t work. Fishman shuttered the company within the year.

All the while, he’d started playing guitar and gigging around town, performing, at first, mostly Dylan and then, eventually, tracing back through Dylan to his early influences: Reverend Gary Davis, Son House, Hank Williams, Big Bill Broonzy, and the Carter Family. He was also becoming interested in New Orleans culture and music. He wasn’t yet writing his own songs.

The dissolution of the American Theatre Company was simultaneous with the end of a “torturous love affair—one of those very dramatic situations where it was like, ‘I never wanna see you again!’” as Fishman describes it. It was one of those rare crystallized moments when you know, in a starkly emotional way, that something big in your life needs to change. So he jumped on a train to New Orleans with the $300 and the little suitcase and his guitar. He didn’t know anyone there.

Fishman stayed in New Orleans for three years, busking and playing gigs—a lot of trad jazz, blues, and country. He came back to New York in 1997 to do more theater, renting an apartment above the Bedford Avenue L stop (which he still has today). But his time in New Orleans proved formative. The music scene in the Crescent City is largely self-enclosed—many of its best musicians have little ambition to make it big in a traditional sense that involves touring and record deals. Rather, they’re looking for the best gigs, and the best bands to play with in town. It leads to a great cross-pollination of styles within what are traditionally very idiomatic genres like jazz and bluegrass. “They have very specific languages, and often draw very virtuosic players,” Fishman explains.

Back in New York, Fishman looked for these types of non-showy, emotionally guided players—virtuosos with serious chops who nevertheless had the capacity to “forget all their information” and just kind of disappear into the music. He formed the first iteration of the Howard Fishman Quartet—guitar/violin/cornet/upright bass—and started busking at the Bedford Avenue subway station. Then in 1999, the group landed an unprecedented nine-month residency at The Oak Room, a legendary cabaret supper club at the Algonquin Hotel. Overnight, Fishman had gone from playing to passersby on the subway platform to entertaining audiences at one of Manhattan’s most storied artistic sites.

The residency was successful enough that A&R agents started reaching out to the Quartet, hoping to sign them as a sort of retro-vintage act. Fishman eschewed these inquiries. “If I’d wanted to go on playing standards from the 20s and 30s for rich white people in supper clubs for the rest of my life, I could have done that,” he says. “But it felt like a straitjacket to me.” It was the first of many times that Fishman’s musical career could have become one consistent unbroken line, only for him to swerve.

He was rapidly establishing his bona fides, though. Fishman recorded an album with the Quartet, and then another one that incorporated folk and mariachi in addition to jazz, and then a third one, appropriately titled Do What I Want, that featured an expanded, rock-oriented lineup. He appeared on NPR’s Fresh Air, Soundcheck, and World Cafe, played in venues like Lincoln Center, Joe’s Pub, the Steppenwolf Theatre, the Pasadena Playhouse, and Le Petit Journal, in Paris (though his favorites are and remain small local listening rooms like Barbès and Pete’s Candy Store), and appeared on bills with artists as diverse as Yo-Yo Ma, Andrew Bird, Nellie McKay, and Odetta.

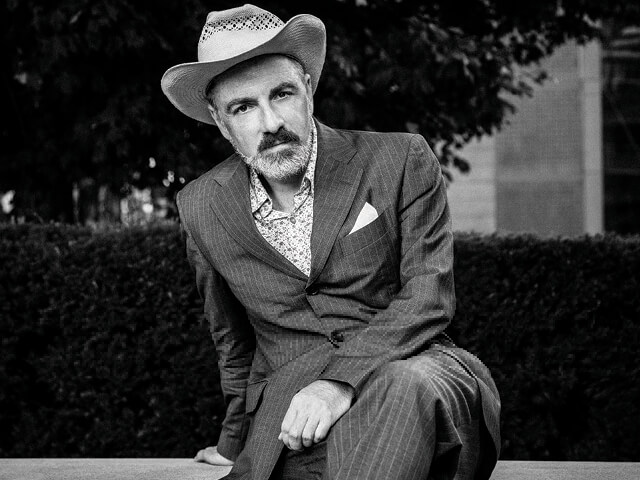

Fishman’s on-stage persona accounts for as much of his appeal as does his encyclopedic repertory. He’s a soulful, intuitive guitarist, and he has a low-key, elastic singing voice. In person, he is often quiet, pensive, ruminatory, but when performing he’s suddenly wild. He’ll stamp his foot, call for extemporaneous solos from various band members, and let out a frequent yawp of delight. He plays to the crowd like a consummate showman, absorbing the energy of the room and reflecting it back out.

“Howard is an incredible bandleader and has an insatiable curiosity about the world and music,” explains Shanta Thake, the Director of Joe’s Pub. “He is able to explore ideas, characters, and musical styles in a way that doesn’t dilute the genre or the source material and bring it into beautiful fruition. It’s so rare to find someone that can easily move between worlds so seamlessly and with such integrity of sound. He’s also just an incredibly kind and generous human. He is a joy to work with and talk through ideas with, which I think is also why he is able to marshal such great musicians, actors and performers of all stripes to play with and for him on all his projects.”

In August, I met Fishman at a coffee shop in Greenpoint. He had recently returned from Chester, Connecticut, where he owns a home, to which he’d retreated with some friends for a weekend of informal play-reading. “I like to do it because I like to read plays as literature,” he told me, “and it’s more fun to do that with people than alone.” Now, we were talking about Werner Herzog’s idea of “ecstatic truth,” the kind of gut-level, sublime truth that is the “enemy of the merely factual,” as the German filmmaker put it.

Fishman is an ecstatic truth seeker, and it’s largely why he rarely rehearses with his bands. He wants the kind of unvarnished, spontaneous musical expression that is the opposite of idiomatic riffing or intellectualized performance. “I want to hear what everyone in the band is really feeling, and I don’t want to let the song go until I get that,” he says. “And then I want us to make something brand new out of those feelings. Somehow, when that happens, you can achieve this magical thing.”

I saw a glimpse of what he meant one month later. I happened to be in Europe following what I’ll simply call a major life change, while Fishman was touring Denmark, Finland, and Estonia for a typically eclectic run of shows—honky-tonk, country, and Dixieland, in various band configurations. Fishman and the Biting Fish brass band were now nearing the end of a marathon four-sets-per-night, three-night gig at Storyville, an American-style jazz club in Helsinki. I flew there. Six weeks earlier, I’d seen him play at Joe’s Pub to celebrate the release of Uncollected Stories; now, here was something entirely different. I was feeling unmoored in general but also specifically, both adrenalized and adrift in my unfamiliarity.

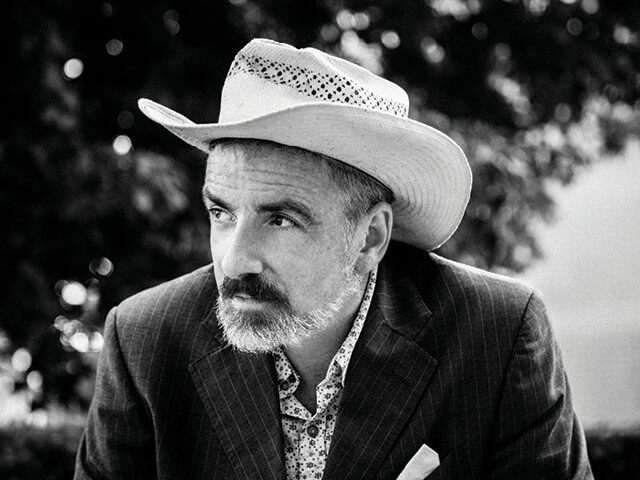

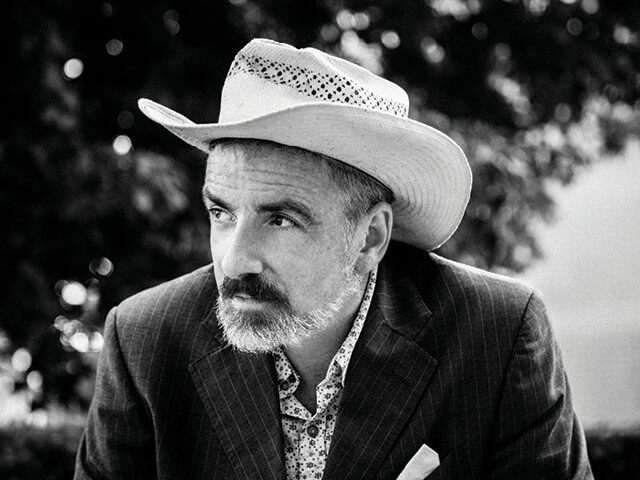

When I arrived, Fishman and his band were between sets. They were sitting in the green room around a long table littered with Corona bottles and picked-at plates of vaguely indeterminate soul food issued forth from Storyville’s kitchen. Fishman was in his typical uniform: worn-in suit, rumpled shirt, frayed straw Stetson hat. The band was tired—their sets each night lasted until 3am and they had about four hours to go tonight.

The club’s cheerful booker, Petteri Hasa, walked in. “I didn’t think that set could be better than the first one,” he said, enthusiastically. This was the third time he’d brought the band to Storyville. He was accompanied by Leah Harris, a soul singer from Canada, by way of Sweden, who happened to be in the crowd and had come backstage to see if maybe the band would let her sing “House of the Rising Sun” with them during the next set? (They did, and it was beautiful.)

Back in the low-ceilinged, dimly lighted main room, the rest of the night is a sweaty blur of Finns dancing unself-consciously; of the casual swagger of the Biting Fish band—Alphonso Horne and Andrae Murchison trading ecstatic soloes on trumpet and trombone, drummer Moses Patrou and sousaphonist Kenny Bentley locking in the grooves; of one man, drunk and middle-aged, blurting “fuck they’re good” when he saw me writing in my notebook. The moment that stuck out was near the end of the night, when Fishman asked Horne to sing the next song. About halfway through, he started scatting. I don’t know if the song called for it or what, but then Murchison went to his mic and sent a volley of pitter-patter back. The two started trading off, now clearly ad libbing, and the music expanded to allow this thing that was being created to fill it up. How to describe it? There was the sense of something mysterious and elusive being brought into existence. I felt it. In the middle of the stage, Fishman was laughing over his weathered acoustic guitar.

The next afternoon, I met Fishman on the rooftop of the Sokos Torni hotel. The air was drizzly and cool. It was 4pm, but he was nursing a coffee. It had been a long night, and he was feeling reflective.

“Five years ago, I would have said that I have no idea what the next six months will look like,” he said. Despite everything, he’d thought, more than once, about chucking his music career. There have been albums that didn’t get the notice they deserved, years that were less hopeful; the kind of instability inherent to a career in music, especially if you don’t have label representation or a manager.

“It felt very precarious once,” Fishman said. “But now I feel like I’ve reached a point where I have some kind of a foothold. I dunno if that means I’m more spiritually grounded in what I’m doing, or what. I just feel more at ease with where I am. I’m not striving towards something that may be related to ego; I’m really just working for the sake of the work, surrendering to reality, and beginning to feel good about that.” ♦

You might also like