Inside the Sumo Wrestling Party at Brooklyn Kitchen

All photos by Clay Williams

The crowd that gathered on the second floor of Brooklyn Kitchen last Thursday was big and enthusiastic, fixated on a projector screen; almost 7,000 miles away, two rikishi (sumo wrestlers) were colliding into each other with a deft force, and we all had our favorite. My (friendly) bet was on the smaller and slimmer wrestler, but in just a few seconds, the more rotund opponent did a side-step to swiftly push my guy out of the ring.

Japan was in the middle of September’s Grand Sumo Tournament, fifteen days of bouts that see all of the professional sumo wrestlers face-off through multiple rounds until a grand champion is declared. By American standards, the sumo matches are no frills: You won’t find jumbotrons, cheerleaders, mascots, food vendors trolling the stands, or even instant replays. And, each bout often only lasts a few intense seconds before a wrestler gets eliminated.

Back in Brooklyn, however, the third SUMO STEW was just getting started. Event organizer Michael Harlan Turkell was setting out the Asahi beer and Nikka whiskey, as well as Japanese snacks (like Kasugai Yuzu Gummy Candy). Meanwhile, chef and Brooklyn Kitchen culinary director Kyle Lowe was busy in front of the stove, cooking chicken Chanko-Nabe, ramen noodle soup, and shrimp “It’s serve yourself, so feel free to eat and drink as much as you want,” he tells us with a laugh, “we only have six cases of beer.”

Turkell, a photographer and food writer by day, has been has been obsessed with Japanese culture for years. “I still get so excited seeing a match,” he explains. “It’s transformative. There’s so much to the tournament itself aside from the fighting.” He points out the technique, the skill, and the discipline involved in the ancient martial art form. However, he adds, “sumo exported to the US is still known more for fat suits at a carnival.” (Or, I think, for the E. Honda character in the Street Fighter video game series.)

In November 2014, Turkell and his wife Megan went on a two-week honeymoon to Kyoto, Japan—a time which happened to overlap with the Grand Tournament then taking place in Fukuoka. When they realized what was going on, the newlyweds bought sumo tickets from a vending machine at at 7-Eleven store, Megan tells me, and then drove the four hours to Fukuoka.

The experience was like nothing that they had ever seen live before: At the center of the large stadium, a ring or dohyo, almost fifteen feet in diameter, was marked out on a clay platform covered in sand. The spectators’ seats were arranged around the ring, and everyone had either packed their own food or purchased bento lunchboxes at the stadium (along with yakitori chicken skewers). The people seated ringside to the dohyo were so close that, occasionally, a sumo wrestler who lost his balance or was pushed would come tumbling down onto their laps.

Like many of the Japanese people in the audience, Turkell and his wife spent the whole day watching the bouts and eating and drinking as sumo wrestlers of various heights and sizes—there are no weight classes in sumo—squared off in the ring, pair after pair, for hours. The way that both Michael and Megan tell me the story, it was clearly the cultural highlight of their honeymoon.

Once back in the States, Turkell decided to recreate the experience (or as close as he could) with his own sumo parties, complete with the bento lunchboxes and Japanese beer. “I wanted to have an educational component of Japanese culture and food,” he explains. While Turkell thinks that no one had ever organized something like this before in the US, pitching the idea to his friend and Brooklyn Kitchen co-founder Harry Rosenblum was easy—Rosenblum liked to think differently.

Rosenblum and his wife Taylor Erkkinen had started Brooklyn Kitchen in 2006 after both amateur chefs tried to make grape jam and realized that there was nowhere in their corner of the borough to buy cooking tools and supplies. Two years later, they began adding classes like pie-making, sausage-making, and whole pig butchering. “Part of it was that, in my mind, if I wanted to see it, so would other people,” Rosenblum tells me.

As their store accumulated more and more products and their classes routinely sold out, Rosenblum and Erkkinen began to search for a bigger space. They found their current location—inside of a former furniture showroom on Meeker and Frost—in a way that seems less fortuitous and more by benevolent design: The door was open, so they walked into the building and chanced upon the owner, who was about to put a “For Rent” sign on the door.

Thus, the relatively-new Brooklyn Kitchen is now large enough to make an impression but is still small enough to be manageable and not overwhelming. There’s an impressive selection of everything that you know you need (teapots, coffee machines, knives, birthday candles); things you might not realize you need (cheese-making kits, hot water bottles); and things that Erkkinen and Rosenblum just think are cool (like the Double Turner Tongs).

“We’re really interested in finding what we think of as the best product and not just the most convenient one for us to put on the shelves,” says Rosenblum of the selection. The aforementioned tongs, he explains, are a favorite of his because they’re well-made and can double as spatulas.

So, naturally, Rosenblum got behind the sumo streaming idea—and he’s since become a sumo fan himself. On SUMO STEW Dai 3, Rosenblum happily mingles with the crowd, drinking beer and occasionally hoovering near the open kitchen, checking on Lowe’s giant pot of chicken Chanko-Nabe.

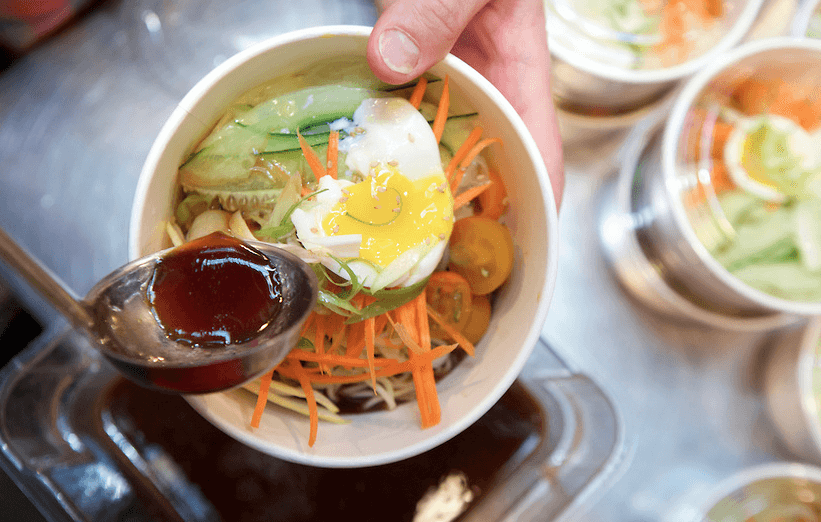

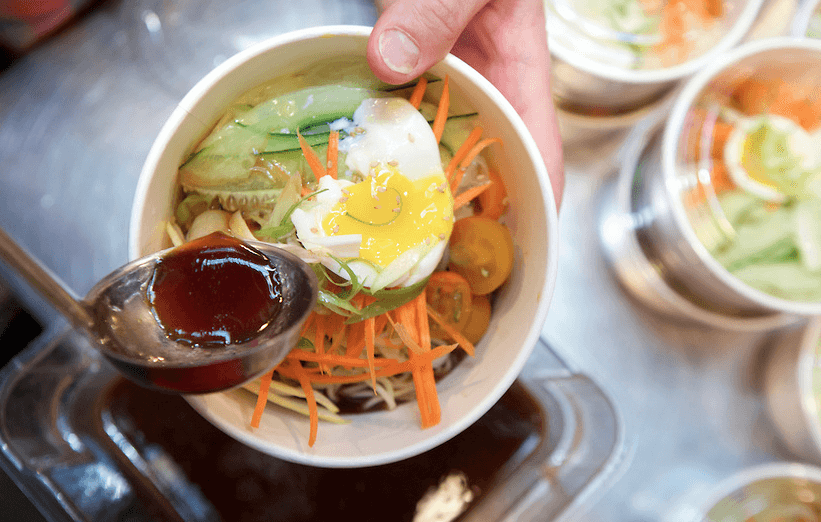

Lowe, who designs and creates the almost-daily classes at Brooklyn Kitchen, works practically non-stop during the event, peeling shrimp, sculpting balls of rice, boiling ramen, and delicately cutting salmon sashimi. As each course is done, he announces what it is, what it’s made of, and that there’s plenty more for seconds.

Behind him, the dishes pile up in the sink. Who does those after the event is over? I ask. “Our porter Victor downstairs,” answers Lowe, without missing a beat, “who gets tipped in meatballs.” He breezily fields numerous questions from the crowd and even patiently allows people to repeatedly photograph him and the food at close range.

“I really just like serving up Chanko-Nabe,” he says, setting out bowl after bowl. His is a house-style, “seasonal-seasonal” variety that has been Japanese-approved by both chefs in the city and sumo streaming event-goers. “It’s fully herbal and very vegetal,” adds Lowe.

In front of us, on the screen, sumo wrestlers continue to face-off into the evening. Everyone eats until we can seemingly eat no more. Then Turkell serves Nikka whiskey highballs, called haiboru, which are popular in Japan. Mine is on the strong side, so I get thirds of the Chanko-Nabe to balance it out—partially because it was that delicious and partially because watching sumo wrestling makes you hungry.

SUMO STEW Dai 4 at The Brooklyn Kitchen is scheduled for November 14. Tickets are $35.

You might also like