The New Normal: Deconstructing Fashion’s Gender Neutral Movement

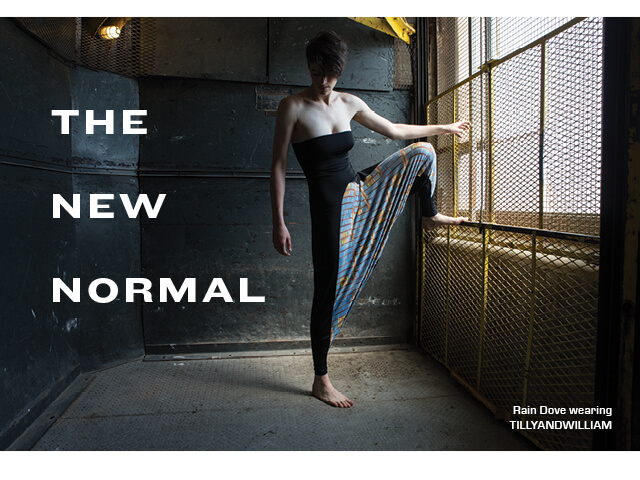

All photos by Ebru Yildiz

“Gender” is undoubtedly the word of the moment. Issues like gender equality, gender expression, gender neutrality, and transgender visibility have become part of our national conversation. Despite still having a long way to go, awareness is spreading, acceptance is dawning, and equality seems like it could one day be attainable.

One of the ways in which the current gender-focused conversation can be viewed is through the lens of fashion. Not only are clothes one of the strongest tools for expressing our gender, they can also be among the most limiting. There aren’t many other public spheres as binary as clothing stores, all still clearly labeled with “Women’s” and “Men’s” sections. And so, it’s hard not to wonder if, as our understanding and acceptance of the gender spectrum evolves, will fashion—one of the most gendered parts of our lives—also evolve?

We spoke with some of Brooklyn’s prominent fashion influencers—from designers to models to shop-owners to bloggers—who are leading the charge to dismantle fashion’s gender binary about the current state of androgynous fashion and the possibility of an inclusive, fashionable future.

Rain Dove is a humanitarian and agender model.

How did you end up getting into the fashion industry?

I was going to UC Berkeley, and I was running a landscaping company, which was awesome—super dirty and stinky all the time. And I took this really beautiful model out on a lunch date, and I lost a bet during a football game to her; she said I should be a model. She said “You wouldn’t have to work so hard! You don’t have to go do a job that’s going to break your back all the time!” Because landscaping was really beating me up, and I was like “Well, I like that kind of life, and I think that models are pretentious fuckers who don’t eat. And if i’m going to buy a $5,000 skirt from Chanel, it better have a dildo built into it that fucks me as I walk.”

Do you think the future of fashion is ungendered? Do you see it moving that way?

I think it really comes down to advertising. If you look at high fashion, you’ll see that designers have always been so open to different sexualities, different gender expression, different movements. The designers themselves are often very free spirited beings, but the advertising parties are like “That’s awesome, but where’s the money?” So I think that advertising and these movements are going to go wherever the money is, so if we as a society step forward and we demand or show that there is money to be made in a particular ideology, then I think that the advertising of fashion will change to go in that direction.

How do you think people in the fashion industry and outside the fashion industry can better support the full spectrum of gender expression?

I think it’s important for everyone to realize you might have a particular sex, but your sex is not directly tied to your clothing. If I wear a suit my vagina does not fall off. I’m not pretending to be a man, I just fucking like dapper shit, right? I think just being authentically you is the most important thing. People tend to shy away from things just because they think they shouldn’t be allowed to do those things, because they feel like society will shun them, but I think it’s one of those things where it’s just like: keep to yourself, do your thing, live a life you love, and don’t limit it. I feel like the world would change a lot faster if people just focused on themselves.

But I don’t want to demonize people who don’t feel as fluid expression-wise. There will always be a place for high heels, a red dress, and blonde hair with size double Ds. Everyone just do their own thing.

What would you say are some personal goals going forward in challenging gender norms in the fashion industry?

I want to be more than a model. I want to be a movement, which is an exciting, kind of pretentious thing to say, but it’s gotta happen and I’m here, so let’s fucking do this shit. My goals are: I wanna be a Victoria’s Secret Angel because I feel so uncomfortable thinking about it. I just went and did Miami Swim Week, and I was so awkward. I want to be on the cover of Playboy—not because I want these accolades, but mostly because I want people to be able to see it’s possible. I want to be able to do a huge menswear brand, maybe Calvin Klein men, which would be awesome. And I want to get into film more than fashion. I really want to play a girl-next-door kind of role in a movie where I’m not lesbian, just the girl next door. Like be the love interest for Ryan Gosling, but totally as myself—and it’s not a big sham or the gimmick or anything.

My goal is to basically take everything that is taboo and put it on a platter and be like, “Here it is!” I think that’s what it’s all about, just showing people that it’s possible to live a life you love. It’s nothing to be ashamed of and you shouldn’t be afraid.

Travis Weaver is the founder of Kickstarter-funded unisex label One DNA.

How do you think we can continue breaking down these gender binaries going forward in the fashion world?

I think it’s all about our youth. I feel like our youth are making the changes now. Friends of mine that are a lot younger that grew up in the suburbs and are heterosexual males, they wear women’s clothes and they don’t think that it’s weird. I have friends that are 16-year-old straight guys, and they paint their nails, and that’s not weird to them.

What do you think will be the role of One DNA and other unisex clothing in the future of fashion?

We will have to generate a trend, which will then have to die out, so that it will just be the way things are. Eventually it won’t be a trend or a fad, it’s just not going to be a subject to talk about anymore because it’s just going to be a thing. I think we need a retailer that has a shop that is only non-gender specific. It’s going to take something like a big company, like a Uniqlo, to open and not label as men’s and women’s. I think that’s what it’s going to take to really really shake things up and change it. If I walk into a store and someone is like, “Men’s is downstairs,” I’m like, “Uh, OK? I’m going to check out the women’s stuff too.”

Jessica Lapidos and Tom Barranca are co-founders and co-designers of unisex fashion line,TillyandWilliam.

How do you define unisex clothing?

JL: We define it as clothing that is made to fit on all genders equally, that doesn’t adhere to historical thoughts on what makes menswear or womenswear. It’s a piece of clothing that you can put on your body that brings out whatever gender you’re hoping to express. You can make it your own and express your gender freely, without feeling beholden to the garment and feeling like it’s going to express your gender for you.

How did the concept for TILLYandWILLIAM come about?

JL: We were originally thinking, “How do we share clothes?” How do a man and a woman share clothes? It was sort of before even examining our own gender so deeply. It was from the level of clothing, how you just take gender out of it. Part of our goal is to make these new shapes that fit the body differently and kind of adapt to each body. When we were looking at these clothes, we were like, “Why are they shaped so differently?” Like why have we just been ok with these gender separations in fashion throughout the past several centuries?

TB: And not only did it not make sense on an aesthetic level, but also, a lot of what we do is make comfortable clothing that you want to move around in and be in all day, and the idea of the suit just didn’t make sense on the level of you just can’t move in it. A lot of what we were doing when we started out was just throwing out everything we knew about clothing and starting over from scratch. It was just like, ok, we’re going to design clothes for humans, and what does a human need? What would a human want to put on their body? There’s no need to design specifically for women or specifically for men.

Is the future of fashion ungendered?

TB: I think that it will be more common to see designs like ours or ungendered fashion, but there are things in fashion that are staples that will never go away, and I think what is interesting is there will always be dresses, button-down shirts, pants, but I think what you’re going to start to see is more fluidity in who is wearing these things. So cisgendered men wearing dresses and women wearing more masculine looking things and there is going to be this middle ground where you’re not sure who is who and what is what, and it will be like, who cares. I think you’re going to see a lot more people expressing themselves how they feel and not how their gender tells them to feel.

JL: From an industry perspective, this industry is so massive and pervasive, so some of the changes that we’re looking for with really gendered clothing and heteronormative clothing, I sort of associate that with the major problems with environmental harshness, exploitation of labor. There are so many problems within the fashion industry that need to be fixed, and we’re addressing all of those things within our own pieces, but I think there are some dinosaurs of fashion right now, these super corporate places that are going to continue to make what they know sells in really harsh ways. I feel like that might just all have to crumble with the revolution of whatever happens next with taking down massive corporations that are ripping the earth and exploiting people for labor, so I think it kind of goes hand-in-hand.

And I agree that people will start wearing whatever they want to wear, but I somehow think that goes hand-in-hand with how we beat all of these injustices in fashion, as well as getting more representation out there with models and who is seen and what kind of bodies are seen.

TB: Also, on a level of artistry even, I think you start hearing every so often that fashion is so unoriginal now. Every decade has been replicated and done and redone over again, and this really is the final frontier of where fashion can go and what it can do. I feel like almost because of lack of originality and lack of options of things you can even create anymore and call original, designers will almost be forced to explore this realm of gender nonconformity, and that’s really, to me personally, so exciting.

JL: Well, that—and embedded technology.

Marie McGwier co-created (and trademarked!) the “Gender Is Over If You Want It” shirt.

How would you summarize your views on gender and gender expression, and how does that differ from what you perceive to be society’s general view of gender?

I feel like one of the ways I think about gender is to challenge it. I feel like the way I dress and the way I’ve always dressed has been this form of challenging gender norms, so it’s this very interesting thing to see bubbling up to the surface. My perception of larger society and fashion is it seems that we’re on the upswing of like general awareness, even just in being able to recognize that things are gendered, and it’s not that you even have to be actively challenging it, but just that it exists at all and being aware of it opens up the opportunity to be like, “Wait, do I like that this exists? Do I like that I have to do this? What would happen if I do this other thing?”

What’s interesting though is because fashion is almost its own institution, I’m curious to what degree do the things we see occurring in fashion actually make their way into legitimate life. Society as a whole isn’t totally in the place to recognize all the multiple levels of gender and how pervasive it is and how oppressive it is for some people. I wish I could say people starting to blur the lines with gender in fashion opened up this total form of acceptance. That being said, just because I don’t necessarily view them as one in the same, I think that fashion is a really interesting place to start, because it is just such a visible form of how you want to represent yourself. It opens up an opportunity for questions.

How do you think people in the fashion industry and outside of the fashion industry can better support the full spectrum of gender?

In an awesome world, if people removed sections based on gender. Right now the top-level structure breakdown of stores is men’s section and women’s section, but within that there is a break down of suits and sweaters and all of that. Why wouldn’t that be the top level structure breakdown? Like, if stores just had: this is where dresses are; this is where skirts are; these are where pants are—that immediately removes gender from the picture and, just makes it OK for anyone to buy anything.

How did you feel about the shirt going viral? And, on a larger scale, how do you feel about this important topic of gender expression potentially being described as a trend?

It’s caused Nina and I a lot of anxiety at a base level. Obviously there’s this ego check when you see Miley Cyrus wearing your shirt on Instagram and it gets over 600,000 likes. You’re like “Oh my god,” and it’s awesome, but immediately after that it sets in, and you’re like, “OK, message control.” How do I deal with message control? How do I deal with all these people that are like “Gender is over!” and drop off the “If you want it,” which is the second part of the message.

For me, when we first started making this project, we had a certain type of person in mind that would be a person who wears it, and that was probably a person who feels oppressed by gender and gender roles. It’s probably someone the message really resonates with and it can do something for, and that’s who we intended it for, right? From there, for different types of people the message just started resonating in various capacities, and I’ve had to have this level of almost accepting people into the gates in a way that’s like, “Do I deem this person worthy to tout my message?” One way that I’ve been able to handle this is by keeping it so DIY. When people want the shirt, they have to tell me what it means to them. I’m really in control of who gets the shirts, so it’s still a relatively smaller project. I could let it scale if I wanted to or I could try to push it out, but I don’t really want to because of this whole loss of message thing we’re talking about.

I think the trend thing that has been interesting is the part that is trending is just “Gender is over,” when the message is “Gender Is Over, If You Want It.” Which underscores and underlines over and over autonomy and ability to make a choice, so it’s a little frustrating sometimes, because it’s catchier and easier to hear and promote. The thing is, the message in and of itself is inspired by John Lennon and Yoko Ono “War Is Over If You Want It,” but obviously in a perfect world, it would say,”Oppressive Gender Roles Are Over If You Want It,” and that would have been the exact message we wanted to craft. Then I don’t think I would have this anxiety around things trending and losing their meaning and all this, because the message would be the exact same as the meaning, but now you have to ideally read into the message a little to glean the meaning, and I think most people are doing that and a lot of people aren’t doing that, and it’s OK, but that’s also the part I’m trying to figure out how to grapple with in terms of it being a trend. I think in practice the way that I deal with it most is when people are saying “Oh these shirts are awesome. Miley Cyrus is wearing it,” I kind of handle it in a way that’s like, “Well yeah, just so you know the basis of this project is blah blah blah. Money is going to this source.” Like, I remember there was this picture of Snoop Dog and Miley Cyrus, and my friends were like, “So when are you getting Snoop Dog a shirt,” and I was like “When he tells me why gender is over if he wants it.” So the way I have chosen to deal with the trendiness of this is by retorting with the meaning over and over again. Like, how else do you hold yourself accountable for spreading a message once it’s bigger than you?

Do you ever see yourself expanding Gender Is Over If You Want It beyond just a shirt? Perhaps to a whole line?

This is something I’ve thought about because—for one—this project is seasonal. The summer will be over, and we’ll just have tank tops, so there’s this place you get to where you’re like, now do I decide to make sweatshirts? Do I decide to make this line of clothing? Mostly I land on no. I’m not 100 percent opposed to it, but I think if I were to do that, it would require me to hand the project over to someone that could handle it, but with that there’s a lot of things—like it has to be not for profit, and all these other stipulations. I just think for me it would start to get tiring managing this all the time. I really enjoy it right now, but I don’t want it to be my life. I want to be able to use my creative energy for multiple projects. I don’t want this to consume me. So I’m not opposed to it, and I’m always willing to listen to opportunities and have these conversations, but I’m not trying to push it, and I think that’s been a thing that’s been really good about this project from the start is we’re not trying to push it. The things that are happening are happening really, really organically, and that feels really special and there’s no marketing power behind it. There never will be marketing power behind it. I think if that means the project will die out, then that’s OK.

Rae Tutera is a feminist-movement and trans-movement activist, clothier at Park Slope bespoke suit company Bindle & Keep, creator of blog The Handsome Butch, and ownder of Bed-Stuy’s Willoughby General Store.

Have you noticed stronger awareness and acceptance of non-conventional gender expression through fashion in Brooklyn specifically?

I often think I actually have no perspective because I spend all my time in Brooklyn. I really don’t leave anymore now that I have the shop. I have a very narrow cultural reality and it’s a reality where not only is it acceptable to experiment, it’s celebrated. I feel like there’s a gender spectrum and there’s a style spectrum, and they’ve become circular in a way where they touch each other, so masculinity gets closer to femininity all the time and femininity gets closer to masculinity and there’s sort of a gender fluidness I see in Brooklyn that I don’t think I would necessarily see elsewhere.

What would you say to someone who takes the topic of gender-neutrality and tries to package it basically as androgyny being a trend?

I would say androgyny is not a trend as much as it’s trending, and there’s a subtle difference there. The same thing is true that trans people are trending right now, but that doesn’t mean they are a trend or that they’re passing. People have always been androgynous, but I think there is always a commodified or commercialized version of every single thing, and androgyny is just one of those things that has been around forever and picked up by the mainstream and packaged in a certain way for consumption, and if that means men’s pants are getting tighter or women’s clothes are getting looser, then that’s a good thing, right? Because that’s what people want. And just because we only see it through the lens of tighter pants and looser shirts doesn’t mean it’s not much more complicated. People identify as androgynous, and I don’t think that’s necessarily part of the media wave. We live in a culture where things trend—like the most bizarre things can trend—and I look forward to when identities I relate to aren’t trending because that means they’ll just be part of the landscape.

What would you say has been your biggest accomplishment as someone with a non-traditional expression of gender?

Well there’s a micro version of that and a macro version to that. So the macro version is that I was outed by the New York Times for having had top surgery, which was not like relevant to the story that they were telling about me making suits. Like, this was a profile on the work I’m doing with Bindle & Keep, and then parenthetically while talking about me, they said that I had my “breasts removed,” and I didn’t know that was going to be part of the story, and a lot of people in my family didn’t know I had top surgery. I think it came out in November and I had surgery in April, and I was still kind of closeted about it, and so that was a real moment for me when I became visible in a way that I hadn’t been prepared to be. But then I decided there was no alternative to embracing it because it was already in print. It was a really scary moment for me, mostly because I didn’t know how people would react, but I got a lot of emails from strangers— gay, cis, trans, all kinds of folks—saying that my visibility was moving to them and they could see I was put in a weird position, and they were just really tender and vulnerable with me and told me their own stories. It was just a very beautiful moment that allowed me to decide I had to be transparent all the time and if my being visible as any kind of person was at all helpful to anyone I was like, this is it. It was a very nice moment.

And the other version of that is just I always assume people mean well. I used to go around and if anyone gave me any kind of micro aggression I would be like, “It’s because they’re transphobic. It’s because they’re homophobic.” I just had this really nasty narrative for other people, and now I’m just like assuming that people have good intentions. It’s kind of zen version of that, and I’m lucky. I had to reprogram my brain. We’re just hyper aware of ourselves and upsetting ourselves.

Jenny McClary and Allie Leepson are a couple and founders of the androgynous fashion line VEER.

How would you summarize your personal views on gender and gender expression?

JM: Gender is a complicated spectrum and people will present themselves anywhere they feel. I think we fluctuate many times in life and need the freedom to express ourselves depending on how we are identifying—whether that be on a daily, monthly or yearly basis. I personally identify as female and I identify my aesthetic/style as androgynous. Androgyny is another subjective word though. To me, it means that it lacks any gender in particular.

AL: I also identify as female and identify my aesthetic/style as androgynous and minimal. I don’t necessarily think people need to give themselves or how they present themselves a label. Obviously some people are set in how they want to present themselves, whereas others will never quite find the right word to describe themselves.

Have you seen a change in the world’s view of gender in the last few years? How have you seen that manifest in the fashion world specifically?

JM: Absolutely! I think it’s becoming more fluid and open, especially for women. The whole notion of androgyny and unisex lines has become more and more prevalent for both men and women! I’m not saying we don’t have to keep pushing forward, but we have options now for any kind of style.

AL: We’re also seeing these blurred lines in the more mainstream fashion campaigns and shows as well. Women walk in men’s shows, men walk in women’s shows—the rules aren’t so rigid anymore.

What would you say to people describing gender neutrality in fashion as a trend?

JM: I don’t even know. Who cares, really? The truth is that whether or not a specific style is trendy or not, our fluidity is a constant. Our grey areas will always exist and it’s more of a matter of continuing to embrace it and not slipping back into more rigid expectations or roles—which, by the way, I don’t see happening. It used to upset me when people called unisex or androgynous a trend. Now I don’t care so much. I’m so confident with who I am and how I express myself that it never appears as though I am the way I am because it’s “in.”

AL: Yeah, who cares! I think the fact that this style did blow up in the way that it did was beneficial to those who do identify that way. It opened up a whole new area for designers to explore. I think it’s safe to say that it’s past the point of being a trend now.

You might also like