A Night at the Latex Ball, the Best Party in New York

“Who doesn’t like a ball?”

A nine-year member of the ballroom scene, Omari Mizrahi, who also goes by Ousmane Wiles, sits in the Civil Service Café on Nostrand and Clifton in Bed-Stuy, a few blocks away from his home. You can hear Brooklyn in his deep, pleasantly scratchy voice.

“The lights, the cameras, the celebrities. Just to be around the atmosphere.”

It is mid-July, a few weeks before the Latex Ball—what Omari calls the biggest and most mainstream event of New York City’s ballroom scene. The Latex Ball celebrated its 25th anniversary this summer. The Gay Men’s Health Crisis (GMHC) has sponsored the annual event as an outreach opportunity—featuring free HIV testing, HIV-prevention materials (read: lots of condoms), and sexual-health information provided by GMHC and other community-based and governmental organizations—since 1990.

2015 also marks the 25th anniversary of Paris Is Burning—the best-known and most complicated documents of the ballroom scene. bell hooks, in her 1992 essay “Is Paris Burning?” calls out the documentary for celebrating “that brutal imperial ruling-class capitalist patriarchal whiteness that presents itself—its way of life—as the only meaningful life there is” and its maker, queer white cis woman Jennie Livingston for turning meaningful ritual into meaningless spectacle. Livingston, according to hooks—and several of the documentary’s participants, who in 1993 attempted to sue for a share of the profits—was “an outsider looking in.”

When Celebrate Brooklyn! announced an anniversary screening of Paris Is Burning in Prospect Park in June, many were shocked by the absence not only of the still-living subjects of the documentary or members of the still-thriving New York ballroom community, but also of any queer or trans person of color on the program. In a change.org petition, a group called Paris Is Burnt called the event an “appropriation of our narratives for the sake of entertaining a gentrifying, majority white audience that seeks to consume us and call it paying homage.” The petition gathered over 1,100 signatures.

It was a particularly injurious oversight in a year that has also seen a precipitous rise in the number of trans women murdered across the United States: According to a recent report from Fusion, at least 20 have been killed since January. (In 2014, New York City Anti-Violence Project recorded 14 murders of trans women nationwide.) In only nine of this year’s 20 cases has a suspect been charged with murder. This too is a through line: Venus Xtravaganza, one of the central subjects in Paris Is Burning, was brutally murdered in 1988, at age 23, while Livingston was still filming the documentary. Her death is still unsolved.

“It’s full circle,” Omari Mizrahi says, considering the longevity and continued relevance of the ballroom scene, as well as the documentary that helped make it famous. Ballroom, he says, is again having a moment. “Because it’s underground—it’s remained underground. That’s what’s kept it so—‘Oh, what’s this?’ —” he says, mimicking the surprise of a casual observer discovering the wonders of ballroom, “interesting to be a part of. Because it wasn’t frequently seen all the time.”

This is all cyclical. “It’ll die down. It’ll go back to being the regular girls at the ball having a good old time. You won’t see the celebrities coming in,” he says. He pauses and thinks. “But then again you might. It might be a part of American culture now, American history—ballroom.”

Omari frequently doubles back, reconsiders, holds two equally true and contradictory concepts together in one thought. This is entirely intentional: it’s a testament both to his intellectual honesty and the complexity of the world he describes. Ballroom itself makes these same acrobatic, counter-balaced moves: its insistence on the malleability of identity, but also the rigidness of categories; its subversion of mainstream aesthetic ideals (the celebration of queer bodies of color), but also its occasional reaffirmation of them (rewarding traditional standards of white-aligned beauty); the community’s underground status, but also its now-omnipresent cultural influence.

* * *

Midway through the Latex Ball, Tasha Mizrahi stands pressed against her house’s designated table. Terminal Five opened its doors at 8 that evening and was supposed close them at 4 in the morning. Almost no one sat the entire night—all eight hours. “There’s usually Rihanna here,” Tasha says, resigned, “but I guess she was just with us in the club.” She meant Esqualita on West 39th Street in Manhattan, which hosts voguing competitions every Monday night. Rihanna, along with Janelle Monae, had stopped by last month. Earlier Omari had pointed out a man in a dusky-rose floor-length skort, a tailored jacket of the same material, and a delicate lattice of white-leather bondage gear wrapped over a lighter pink shirt and masking, too, his face. “That’s Rihanna’s hair stylist, Yusef. House of Mugler,” he says. Everyone feels Rihanna’s absence keenly.

Raven-Symoné is the night’s designated celebrity—and while she looks fierce (yes) in her black lipstick, she loses the audience as soon as she takes up the microphone: She immediately launches into a story about getting in trouble on black Twitter because she tweeted #AllLivesMatter. She speaks for a while in hashtags. “Hashtag black lives matter, hashtag ALL lives matter!” The room is politely disinterested.

Symoné’s introducer, MC Debra, in white denim and a yellow Mickey Mouse shirt, the letters of her name (helpfully, for me) ironed on her back, retakes the room. “This is the 25th anniversary Latex Ball!” she shouts. “You are proud and alive!”

She and her co-emcee, Kevin JZ Prodigy, move effortlessly between paying tribute to the past (“Can I see! Royalty!”) and teasing the present (“When I say face I mean face—no chicken grease lips. Some of your girls don’t understand this cause some of your girls don’t got it”). She welcomes up Tracy Africa—who worked as a successful runway and commercial model in the 1970s and 80s until “some shady fool” (according to online message board Lipstick Alley) outed her as a trans woman: “Tracy Africa, the icon, we love you.” She walks slow and regal.

“What’s really ballroom today?” Debra asks on stage. “A girl who can just come out and play, in a towel, a fur. This is what you call Mariah Carey, James Bond girl. The Honey girl, the Honey girl. The East Coast, the East Coast.”

She speaks, rhyming, repeating, over an omnipresent house beat. (“High energy, nothing from the south,” she instructs the DJ.) “Chic, chic, shitty, chic.”

* * *

The 2015 Latex Ball features 25 categories: best dressed; pop, dip, and spin; women’s face; fem queen runway; new way vogue; women’s runway; realness; labels; bizarre; women’s vogue; small boys runway; butch queen face; butch queen performance; big boys runway; fem queen face; team sex siren; tall boys runway; drags face; fem queen performance; body (subdivided into women’s, transman, fem queen, butch queen muscular, models); twist vogue; all-American runway; drags runway; drags performance; butch face.

“Ballroom has its own language,” Omari says in the coffee shop. Some categories are open to all, others clearly subdivide by gender and body type and expression. There are the categories that rely heavily on clothes: best dressed, labels, realness, bizarre, runway. There are the categories that reward pure looks: face, body, team sex siren. There are the categories focused on dance: vogue; performance; pop, dip, and spin. (Traditionally all dance categories were known as “performance,” but as ballroom’s dance forms have evolved so have their descriptors. Voguing, in a general sense, happens in all the dance categories, but different and specific iterations of it.) Very broadly: fem queens are trans women; butch queens are more gender queer; women are cis women; drags are gender performers; boys are cis men in small, medium, and large sizes; and trans men are trans men. There is some wiggle room—the label category is subdivided into male figure and female figure. “No matter if you’re this, that that that,” Omari says, “if you are considered to have a female figure, then you can walk that category.” A cis woman, a fem queen, a butch queen, a small boy, a drag performer could all walk under female figure so long as they nail the presentation. And this is just at one ball.

“You can’t get upset at the way ballroom walkers or participants talk at the time of a ball,” Omari says. “Yes, you may consider yourself a trans woman/trans man, and yes, we have adopted those terms. We’ve added categories: trans man realness instead of butch realness, or butch this, drag. Drag is performance—but that’s what the category is calling for. For you to come to a ball as Joe and get up in drag to become Joanne and walk your category.”

“Fem queen is as accurate as transwoman to me. Some people might beg to differ. Some people might say yes, but there are some differences. I might say yes, there are some differences. But fem queen—it’s a term within ballroom. Drag queen, it’s just a term within ballroom.”

“I still think these terms are appropriate,” Omari says. But he also, equally, insists: “Trans for me is real life. Trans for me is real life. I’m going to respect that.”

* * *

“Y’all looking like Subway sandwiches on sale,” MC Debra says to a group participating in the realness category. On stage the first set of judges (two groups each do a four hour shift) portion out a birthday cake on the dais. In one corner judge Stanley Milan sits with his daughter, who looks to be in junior high. “He takes her everywhere he goes,” Omari says. She has on the kind of dress a girl her age would wear to church: dark and knee-length and A-line. She looks, explicably, bored.

On the floor mill audience members and participants—mostly participants—dressed up as ancient Egyptians, spider queens, lizard people, b-boys, super models, birds of paradise, nuns, Bollywood starlets, cigarette girls. There are even two crust punks. The bathrooms—which Terminal 5 divides by gender—are thoroughly neutral tonight, and are more dressing rooms than anything else. Body suits are peeled off, heels squeezed into, white greasepaint smeared onto a bare face. A woman wears a trashbag thong and a bustier made of spray-painted gold plastic spoon heads. (She is walking the bizarre category.) Another wears an Ikea paper lantern as an Elizabethan ruff. A person in a Peter Pan hat sprinkles glitter down on themselves. Cruella De Vil and Ursula pose for a picture. “Sea witch fish,” says MC Debra. She measures her foot against a heel that had been lost on stage.

“Everyone waits to see female figure performance, whether you are a real biological woman, whether you are a butch, in drag, whether you are a trans woman, whether you are a fem queen,” says Omari before the ball. Fem queen performance also has the night’s biggest prize: $500. The next highest is realness, with a cash award of $400, but because groups of four walk in that category it’s only really $100 per person. No other individual award goes above $300. “They come to see the fem queens—these women who live their lives as women, who fight their lives as women, and come out to just show their femininity.”

“Face is anticipated,” he says. “Everyone wants to see who is the most gorgeous in the room tonight, who has that skin that is flawless, who has the teeth that is sparkling. The teeth when you look to the side and they smile at you, it gives you that *ding.*” He demonstrates, with the sound effect. “You ever see that in movies? I used to love that. I used to always want to give that. I hope I’m doing that, maybe. You have to find the light.”

But, he says, “vogue is definitely the category you see and hear about the most. You don’t hear runway classes, face classes, realness classes. You hear vogue classes. Whether it’s the old way—which I call that vogue—or the new way, which has elements of vogue—I call that vogue fem.” He breaks down the five elements of vogue fem. (Don’t worry, none of them are knowledge.) There’s cat walk (upright, swivel hips), duck walk (squat, still a-swivel), spins and dips (balletic turns and then hard slams), hand performance (the part you remember from Madonna’s “Vogue” video), and floor performance (writhing, electric, horizontal).

Vogue proper, as he describes it, is “very precise. No room for mistakes.” The movement is “almost martial arts, hieroglyphics. Very much about the shapes and lines, the connections you made, catching the beat. Seeing how well the body can stretch or bend into these weird pretzel-like positions. Beat to beat. That was amazing to watch.”

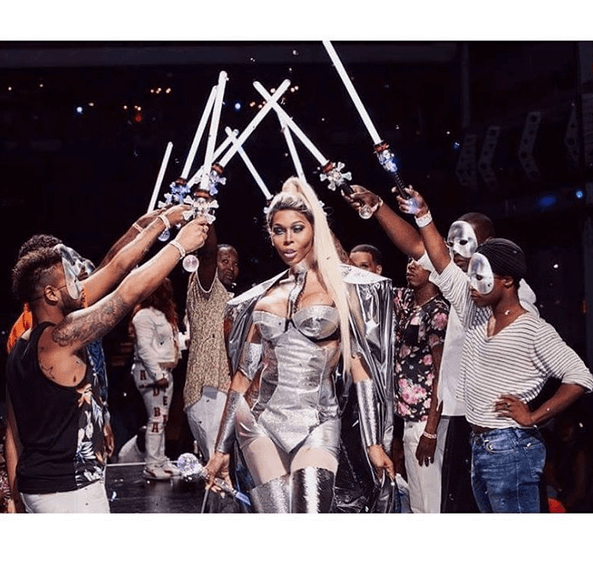

Latex Ball 2015

photo by Anja Matthes

“Now it’s a little more fluid,” he goes on. “We have room for mistakes, to give room for correction, to give room for that wow factor. It can get a little messy. A lot of performers today are so caught up in, ‘I need to hear the ‘uh’ at the end of my dip’ or ‘I need to see the crowd go crazy,’ that they lose the precision, the line.”

“No matter how far you go forward, you always have to remember where it comes from,” Omari says. As a professional dancer, choreographer, and teacher, he’s invested in these questions. “You can still have that wow factor and not be boring and still give me the precision and technique. It’s your creativity. That’s what pushes your creativity.”

“I’ve seen ballet dancers freestyle, hip-hop dancers freestyle—you still see the technique, the clean steps, the movements, the feeling, the emotion behind it, the facial expressions. You ever seen a hip-hop dancer? They look like they want to fight you. Now I see voguers, they just want to swing their hands in the air, they just want to snap their backs.”

“I’m not that kind of voguer,” he says. “I have to give you emotion behind every movement that I’m doing. I have to give you a reason to keep your eyes on me. I have to tell you a story and that story has to keep going. There’s room for a period, there’s room for a comma, there’s room for an exclamation point, there’s room for a question. It’s my creativity. I stick to the art. That’s what voguing is. Voguing is a form of art.”

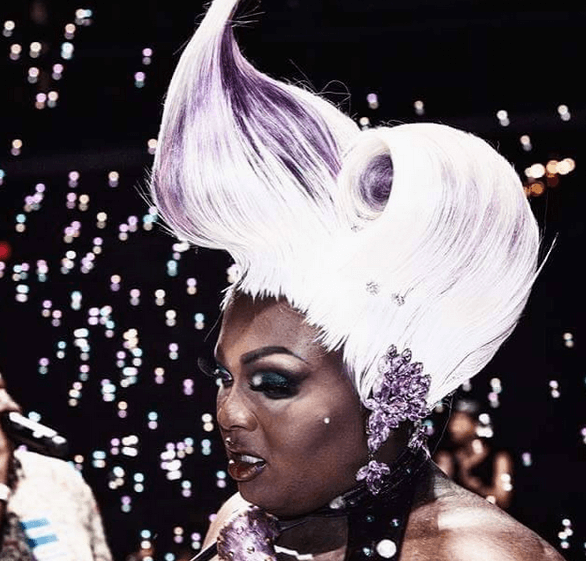

Omari competing in the Butch Queen Performance category at the 2015 Latex Ball

photo via Omari Mizrahi

On the night of the Latex Ball, Omari competes in the butch queen performance category and he wins. Seven members of the House of Mizrahi walk with him—the largest number the house has sent out for any category that night—and those who haven’t been eliminated share the award.

Off stage, all the Mizrahis wear floral prints. Their house table—which can run $150 to $200 per ball—is covered in bags. Leather duffle bags, backpacks, plastic bags from Dr. Jay’s and Supreme Hair. There are condoms everywhere, like confetti. Postcards offering services for homeless LGBTQ youth from the Ali Forney Center. A spotlight series—little booklets that look like trading cards—featuring young members of the ballroom scene speaking openly about their relationship to condoms and STIs and sex work. “So one day I woke up and realized my throat felt different and then I was like ‘uh uh,’ something just isn’t right,” Kalik Mulan Prodigy’s card unfolds. “It was a battle to get him to using [sic] condoms again but I couldn’t take any more risks with my life,” reads Kassandra Ebony’s story. Sequins come spilling out of an unzipped bag, and suddenly someone has a can of 3M Multi-Purpose Spray Adhesive. Long white gloves are spangled with glitter and still-wrapped condoms. Half of a soft pretzel has been abandoned on the table. A maroon fedora moves around its perimeter.

When a Mizrahi walks in a category, a call goes up. “Miz-a-raaaahi, oooo!” (Nearly every house member I spoke to added this extra middle syllable, Miz-a-rahi, in both normal speech and chant.) It’s like a cheer at a sports game: insistent and loud as hell.

One house member, who had been leaning over the stage, red-faced with volume, turns back. “You all need to be screaming. Tap tap bitch!”

Eyebrows are raised. “You got to keep the heat in your pants,” another says.

A third shouts back, “We gotta keep a positive vibe!”

Andrea Mizrahi has been coming to balls since she was 15—she’s 23 now. Jordan Mizrahi joined the scene at 16, and just started walking the performance categories in the last year, at age 22. Before, he competed in face categories. He used to be afraid he wouldn’t be let into balls because of his age. Koppi Mizarahi is the House of Mizrahi’s Tokyo mother.

“This is Xyza Mizrahi, our newest member from the Phillipines,” someone announces at the table. “Everyone say hi.” Wrapped up in spray adhesive and chants and watching, well, everything—only a few people do. Andrea and Xyza compete in women’s performance, Xyza’s also a finalist in women’s face. Koppi wins that night for pop, dip, and spin—one of the few categories that are open to all.

* * *

“The houses themselves have changed, how they are run, how they’re looked at,” Omari says in the coffee shop, reflecting what has changed over the past 25 years. “Some houses are run like families, some houses are run like businesses, some houses are run like sororities. Houses are supposed to be a family, a second family that accepts you no matter what. You still get a sense of that in ballroom house, but a lot of times you get pressured to walk. They all want to see you on the floor. They want active members. That’s one thing about Mizrahi—we are a family before we go into ‘Oh we have to walk this ball,’ ‘you need to walk this ball.’ But we do encourage you to go and stand and explore and put yourself out there for the world to see and build your confidence. That’s what ballroom helped a lot of people coming up in Paris Is Burning. To be ready to take over the world, the mainstream world.”

Omari talks about the women’s scene and the kiki scene—newer, albeit smaller, satellites to the main ballroom community. “They came out of the woodwork,” he says of the cis women who walked the Latex Ball in 2014. “From Sweden to Russia to Norway—these women came from Japan, Hong Kong, Korea. The line was at least 30 women deep last year just for one category.”

The theme for this year’s women’s vogue category is “warrior effect” and the runway is full of so many swords. Costumes reach deep into the cultural well, pulling out nods to Xena, Poison Ivy, Sailor Moon, ninjas (hello House of Ninja), American Indians, Persian warriors, Mad Max: Fury Road. Four cis women from the House of Mizrahi compete. One, Shea Mizrahi, wears the Iranian flag, the words “Respect yourself and your loved ones, practice safe sex” written in Farsi on her arms in body paint. A performer from another house, dressed in the broad strokes of a Plains Indian costume, launches onto the stage backed by a man waving a giant red flag that read “Stigma spreads disease.”

As the competitors are whittled down, a voguer from the house of Chanel—in the middle of a floor work pose—is frozen by the MCs as the judges evaluate her performance. Pose held, she raps her palm against her crotch, her final flourish, until they deliver a verdict. When Inxi Prodigy—a Swedish cis woman in Poison Ivy-wear—finally takes the prize, MC Debra asks: “Are you a real woman? You were born a woman?” and then turning back to the judges, “She can have a baby. She’s got a pussy.”

The kiki scene takes its name from an onomatopoeic term for gossipy laughter, which Dorian Corey uses in Paris Is Burning (“You get in a smart crack, and everyone laughs and kikis”), that has metonymized into a term for the gossipy gathering itself. “The kiki scene is like the underdogs, the new generation that’s trying to come up,” Omari says. It’s a space to first learn and then practice the rules of ballroom, “so when they join the ballroom scene, the real mainstream houses, they come in with an understanding and a knowledge of how things work. Rather than when I came up,” he says, laughing his deep scratchy laugh, “it was just throw me out there to the wolves and hopefully I grab me some meat.”

“The venues have gotten grander,” he says. Terminal Five, while no great looker of a building, is certainly both bigger physically and culturally than the room in the Imperial Elks Lodge where much of the ballroom footage in Paris Is Burning was filmed. “There’s less trophies and more cash,” Omari continues. “Before you would even get in your category, you would still receive your trophy. Now it’s like, okay you got sat down, that’s it, stand to the side, return back to your seat or your house table. The cash prizes have escalated to over $10,000. For their talent, yes!” He says it like he is reassuring himself it is true. That it is, even, right.

He talks about how many more balls there are nowadays. “Before you would have maybe four to six balls a year. Now it’s like six balls a month.” Many of the balls are formalized through a board-approval system, but there are plenty of informal balls too: for birthdays, for holidays, for House members visiting from out of town. “Hopefully no more,” Omari says of the frequency. “I don’t think we could do a ball every day. People would be in pain.”

The 2015 Latex Ball’s theme is “Year of Legends.” In addition to the prizes that go out to the competitors, awards are given to community members. They are in part testament to the enormous losses the community has suffered from both the AIDS epidemic and to larger systems of oppression and exclusion. So many of the awards are named after the dead: the Octavia St. Laurent Trans Activist Award—St. Laurent appeared in Paris Is Burning and died of AIDS-related cancer in 2009; the Pepper LaBeija Image Award—LaBeija appeared in Paris Is Burning and died of a heart attack in 2003; the Willi Ninja Supreme Award—Ninja appeared in Paris Is Burning and died of AIDS-related heart failure in 2006; the Avis Penda’vis Angel Award—Penda’vis died in 1995. There are also awards named after the living: Hector Xtravaganza, Luna Khan—who, as a part of GMHC, organizes the Latex Ball every year.

It’s gone back a long time, Omari says. “Harlem Renaissance long. We used to dress up and do pageants. It was both whites and blacks, Latinos. With the House of Mizrahi, one of the original founders was a white woman. Everyone thinks it’s all gay gay gay, but it wasn’t. It was a white woman—her name was Heidi. Her and Andre Mizrahi, who performed at the Apollo Theater here in New York City. He’s gone on to perform in movies like Honey. He had a nice scene in there.”

Omari is ambivalent when it comes to the question of cultural appropriation. On the one hand, he says, “It’s really nice to get good coverage. Coverage that isn’t just ‘It’s where drags go,’ or it’s ‘where the gays go.’ It’s really not. It’s open to everyone. It’s open to anyone who loves to perform.”

He also thinks about the question as a dancer. “As someone who started off with West African dance, very traditional, then going into house and then finding vogue, I still use a lot of what I’ve been taught in my voguing. When I teach classes I incorporate other styles into it. It’s okay for people to be a part of something and want to share it with the world and do it.” But, he insists, there’s “also a level of respect, an acknowledgement of where it comes from” that’s just as necessary. It’s important to be upfront about where these things come from—language, moves—so that when people outside the subculture discover their origins, they aren’t shocked or disgusted.

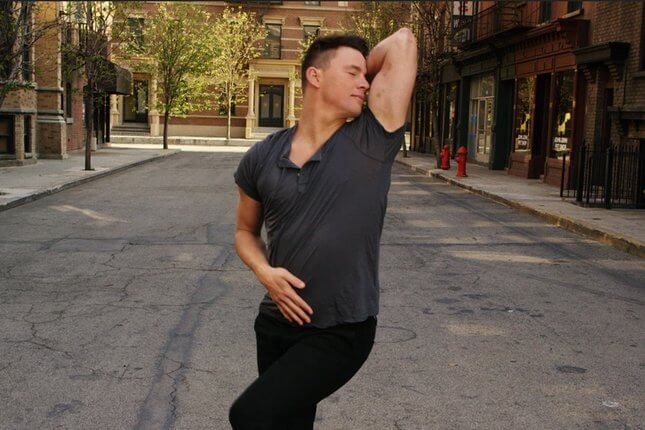

He ran off a list of nearly everything mainstream that has its roots in ballroom: a dance called the 5000, Madonna’s “Vogue,” Channing Tatum’s brief voguing scene in Magic Mike XXL, J. Cardim’s “Breathe Thru the Years” (“I’m filled with this realness / … / Get twist with just a flick of a wrist”), the words shade and fierce and work and read and realness and yaaass. “Come on,” Omari says, “There’s a difference between saying ‘yes, bitch, yes’ and ‘yaaass bitch yaaass.’ There’s a complete change of tone and voice.”

“FKA Twigs—that’s one artist that I respect,” Omari says. “She did not just do voguing. She learned it. She went to those from came from it, learned from them, and not just took it and went to some industry dancers and taught it to them, but got dancers from the ballroom scene and put them in her video. There was only one dancer from the ballroom scene in Madonna’s “Vogue.” All the dancers that did the voguing section [in FKA Twig’s “Glass & Patron” video] were all from the ballroom scene: All have competed and lived and chopped and gotten 10s across the board.

“Go ahead and use this, use that,” Omari says, “but acknowledge where it comes from so that people are no longer scared or putting us in these boxes. We’re not dolls on sticks, we have names. We have lives outside of ballroom. Some of us are stylists, some of us are designers, some of us are lawyers, some of us are journalists, some of us work with kids. Every single day of our lives.”

* * *

So much of mainstream media attention to ballroom has been one of (at least attempted) translation: what is this strange thing, what does it mean, how can we take pleasure or draw interest from it. Though ballroom is perhaps more international, multi-ethic, gender plural than it ever has been, it’s still not a space I—a straight white cis woman—belonged to, though I think my hand performance has gotten better (in the privacy of my apartment) since July. bell hooks, in “Is Paris Burning?” wanted Jennie Livingston to address “the difficult questions underlying what it means to be a white person in a white supremacist society creating a film about any aspect of black life.” But the problem with Paris Is Burning is less that its maker does not acknowledge her position of relative power (though this is a problem!), and more that—for so long—it was seemingly the only document to be had.

What has changed, really, since Paris Is Burning, has less to do with slang or house structure or demographics or the nature of vogue as an art form—though these are all important in their own way—it is how the community has begun to record itself. Members of the ball scene didn’t, in the late 1980s, have cell phones they could make videos or take pictures with, YouTube or Instagram to upload them to, Tumblr to catalog and connect them with, Twitter to throw shade across. In 2015, the archive, both of contemporary ballroom culture and its history, grows. The YouTube account Ballroom Throwbacks TV not only posts a continuous stream of recent videos to an audience of over 38,000 subscribers, but it also hosts a dramatic web series set in and cast from the New York ball scene. Luna Khan hosts his own YouTube show (last updated about a year ago but with hundreds of archived episodes) where he interviews legends and icons of the ballroom scene. A group of unofficial archivists upload VHS tapes of balls from the 70s, 80s, and 90s: cutting them into sections, dating them, and describing them. You can watch the founding ceremony of the House of Mizrahi at a ball in 1992: complete with golden litter, laurel leaves, scepters, and a wizard. It’s a wealth of material, albeit unorganized and ad-hoc, astonishing in its depth and breadth and richness. Who needs Paris Is Burning when you can have this?

You might also like