Meet the Lady Taxidermy Artists of Brooklyn

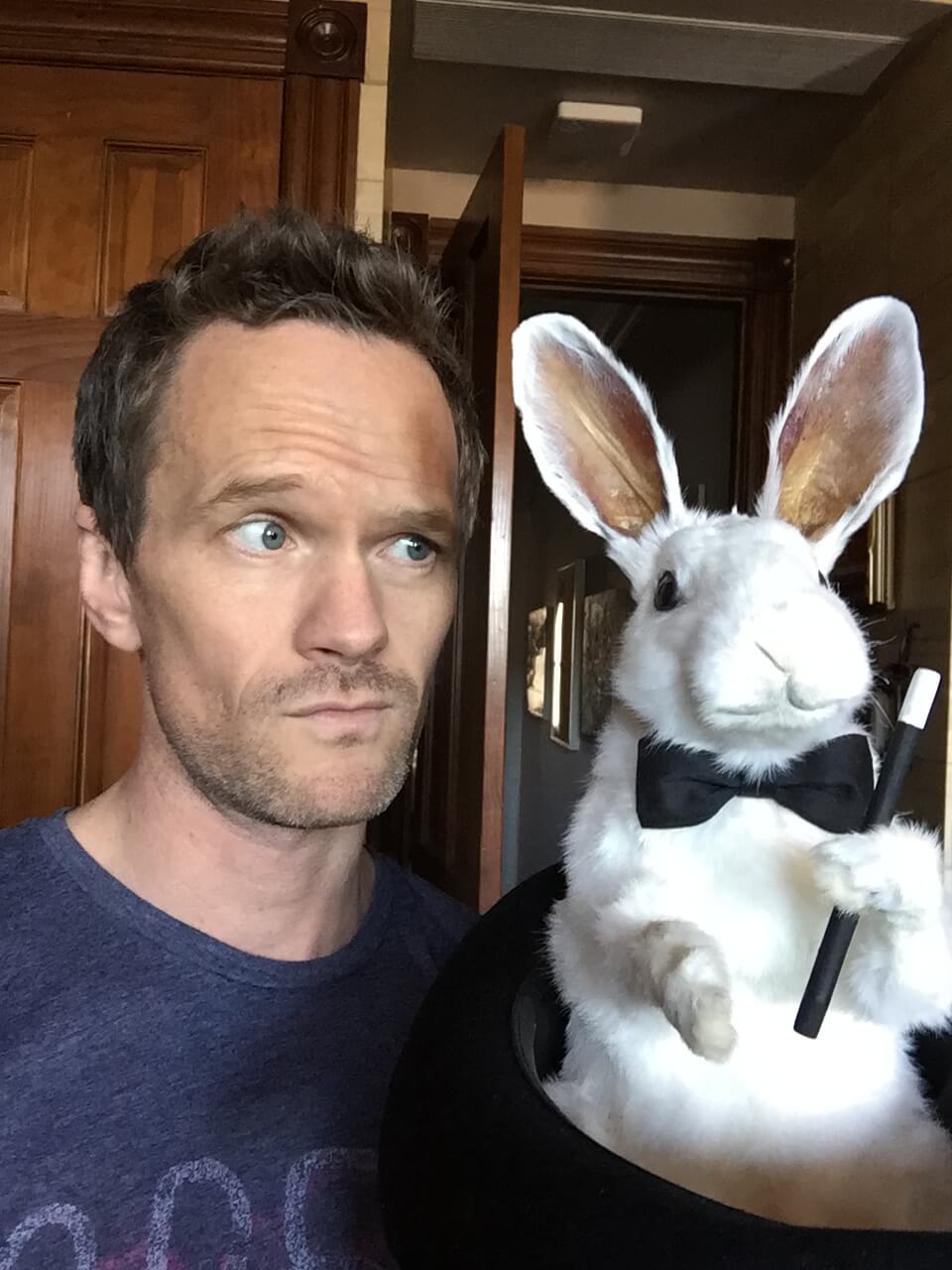

A rhinestone-bedazzled piglet, a baby chick dressed up as Pikachu, a pair of bear cubs with human faces: This is a random sampling of the work of Brooklyn’s thriving community of taxidermy artists, who have made careers out of transforming dead animals into uncanny sculptures. They teach sold-out taxidermy classes at the Morbid Anatomy Museum, hawk their wares at the Bell House’s Rogue Taxidermy Fair, and fill a staggering number of custom taxidermy orders, sometimes from clients like Neil Patrick Harris, a proud owner of a stuffed “magic rabbit.”

Not since the Victorian era, when Walter Potter made insane dioramas from stuffed kittens and game heads on walls were emblems of hunter pride, has taxidermy been so popular. But whereas Victorian taxidermy was male-dominated and either about the supremely macho or the ultra-cutesy, today’s taxidermy artists are mostly women focusing on the surreal, macabre, and sculptural. What’s behind taxidermy’s modern revival? “There’s this movement in our society where people live in denial of death,” taxidermy artist Divya Anantharaman says. “It’s a meditation on mortality to work with dead animals. Taxidermy has helped me make peace with death and spark some worthwhile conversations. It makes me live a more fulfilling life.”

We talked to five women shaping Brooklyn’s taxidermy art scene about their creative processes, the oft-misunderstood practice of taxidermy, and why everyone and their mother seems to be into mounting animal carcasses lately.

DIVYA ANANTHARAMAN

Divya Anantharaman, from Miami, Florida, brings her former passion, fashion design, to her taxidermy art, using lavish materials like pearls and flowers to accessorize her mounts. She’s inspired by fashion illustrators like Mucha and Aubrey Beardsley, as well 19th-century taxidermist John Edmonstone, a Guyanese slave who became a taxidermy teacher after he was freed. (Charles Darwin was one of his students.)

What does taxidermy do for you that other mediums don’t?

I’ve always loved art and science, and the way they overlap and feed into each other. Taxidermy combines the best of both these worlds. It’s also a meditation on mortality to work with dead animals. I’m very comfortable with the inevitability of death, and it makes me live a better, and more fulfilling life. Taxidermists also have a very particular sense of humor because of this.

A lot of people think taxidermy is gross, but when done properly, taxidermy isn’t any more gross that another practice that involves working with leather. I’ve seen much grosser things as my time as a shoe and leather goods designer than I have while doing taxidermy. There’s also this movement in our society where people live in denial of death. Taxidermy has helped me make peace with death and spark some worthwhile conversations.

KATE CLARK

Kate Clark makes some of the eeriest and most elaborate taxidermy work in Brooklyn: She endows mammals with ultra-realistic human faces, bringing your worst Animorphs-inspired nightmares to life.

What does taxidermy do for you that other mediums can’t?

My concept for the work was to talk about what made the human face so communicative and why animals didn’t develop similar features. When I started working with animal hide, I realized that it’s embedded with emotion that can be transformed into powerful and poetic artwork. I use real hide because when my viewers are confronted with the human face seamlessly connected to the animal body, it’s very important that they see that the animal’s skin, shaved and repositioned, has the same porous and oily qualities that we have in our skin. Only real leather has that quality, that ‘truth’ that allows for an intimate connection that encourages the viewer to acknowledge the animalistic inheritance within the human condition.

What is your creative process like?

The process of starting a sculpture begins when I position the body form and traditionally stitch on the hide, knowing that I’ll probably re-position the body before the piece is complete. I then take off the foam animal’s head and begin sculpting a human head out of clay– using a model for reference. I sculpt the clay and position the leather over it–stitching it together and pinning along the seams to show volume and to hold the leather in place. I use the animal’s facial skin over the human features, shaved to reveal skin like ours, leaving animal details but making sure the face still reads as human. For example, the eyelids are always the original eyelids of the animal. The process of sculpting the face takes months.

AMBER MAYKUT

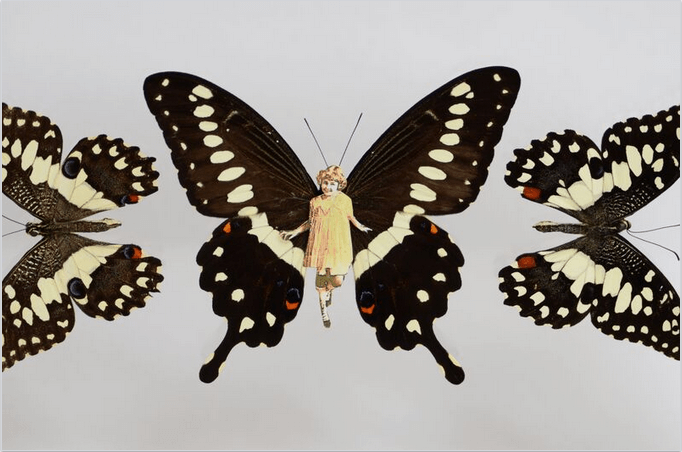

Originally from New Jersey, artist Amber Maykut teaches mice taxidermy and butterfly-pinning classes at Red Rose and Lavender flower shop in Williamsburg. About half of her projects are custom requests from people who discover her popular Etsy shop, Hoardaculture, while the other half are random projects “spurred by something I found at a junk shop, like an antique doll’s dress or interesting piece of fabric, or a wood box I’d like to fill with butterflies,” she says.

What does taxidermy do for you that other mediums can’t?

I think taxidermy pieces have a mesmerizing presence. In a way, the skin of an animal stretched over a form is really just a fancy piece of upholstery or decor. But encounters with taxidermy are as different from encounters with leather boots and hamburgers as they are from encounters with living animals, photographs of animals, or videos of animals. Taxidermy isn’t just a sculpture or interpretation or representation of an animal. It’s the animal itself blurred with people and their attitudes towards death, their gestures towards remembrance, and their complex longings to capture beauty. Taxidermy is more than the sum of it’s parts; it’s not purely animal and not fully manmade, it’s a loaded piece of art that stirs complicated feelings of sometimes shock and sometimes awe, at least for me.

Why do you think taxidermy art is so popular right now, specifically in Brooklyn?

The artistic re-creation of an animal using the animal’s own skin is undeniably a very weird practice, but it was popular in Victorian times too. I think there’s a big maker movement happening, especially in NYC and other big cities, where people are sick of their cubicles and office jobs and want to take their hands off their phones and keyboards and make art and learn a craft. Taxidermy blends science and art, sculpture and anatomy, nature and fabrication.

EMILY BINARD

Emily Binard was 14 when she had her first taxidermy experience: “I assisted a lifelong friend of mine attempt home taxidermy on a bat he found dead in his garage, she says. “e didn’t use any preservatives other than salt, as he had no prior taxidermy experience either, and he just removed the innards and replaced them with polyfill stuffing, them mounted the bat on a plaque…he still has it and it has actually held up fine for 25 years so far!” She’s now a regular at Morbid Anatomy Museum’s taxidermy classes.

Neil Patrick Harris with his custom “Magic Rabbit” that his husband David Burtka ordered from Binard for his Christmas gift.

What does taxidermy art do for you that other mediums can’t?

I grew up in Michigan, so taxidermy was pretty common in the hunting/fishing culture there. Growing up, my mom and my older sister were really into dollhouses and miniatures, and included me in their obsession, so my anthropomorphic taxidermy dioramas offer a way to combine my love of miniatures with my love of animals in a fantastically weird and fun way. Plus, the ethical sourcing aspect of my work allows me to recycle deceased animals and parts that would otherwise go to waste. I like being able to give new life to things that would otherwise be discarded. By ethical sourcing, I mean that I go to lengths to use already deceased animals, and animals that would otherwise be discarded by other industries.

KATIE INNAMORATO

Katie Innamorato teaches taxidermy classes at The Morbid Anatomy Museum, has been featured on the TV show “Oddities,” displayed pieces at La Luz de Jesus Gallery in Los Angeles, and is a board member of the Garden State Taxidermist Association.

I think taxidermy for a lot of city folks is a way for them to bring nature inside and connect with something that’s been lost.

You might also like