A Brooklyn Artist’s 9/11-Inspired Vision of a Dystopian New York City

Bushwick-based artist Calder Kusmierski Singer grew up in a loft on TriBeCa’s Murray Street, just three blocks away from the World Trade Center. He was eleven years old on September 11th, 2001. At the time the planes hit the Twin Towers, Singer was sheltered in his uptown middle school. “I had no idea what was actually going on,” he says. “I heard that two small planes crashed into the towers, implying a minimal amount of damage and casualty. Oblivious to the reality, I was only excited to get out of school early.” Singer’s parents and sister managed to evacuate from Lower Manhattan and walk five miles uptown to find him. His family spent the night inside a projection booth at the Museum of Modern Art, where his father, Greg Singer, worked in the AV department.

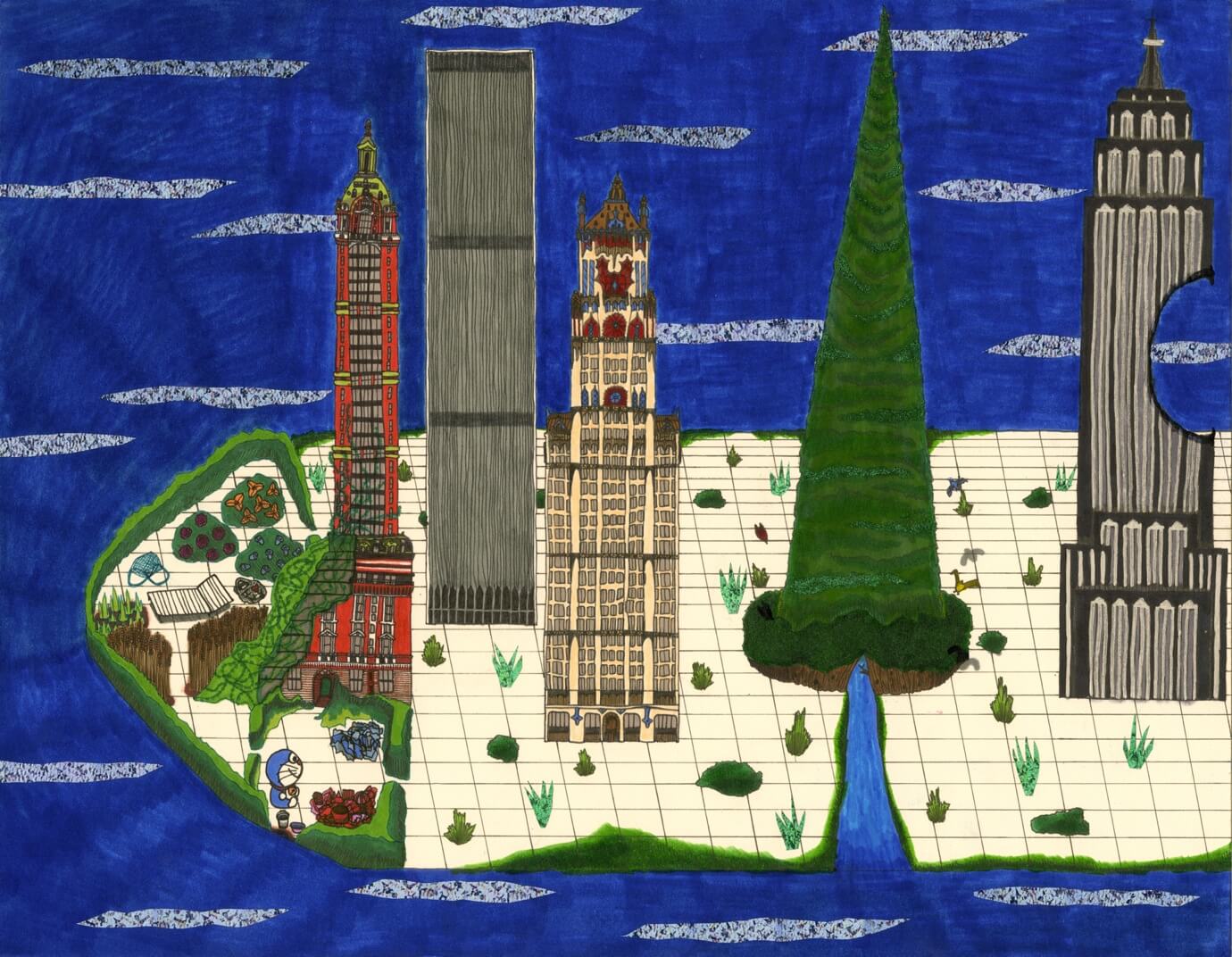

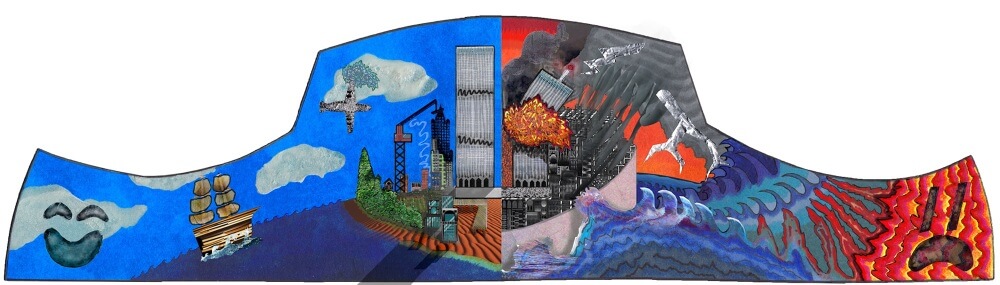

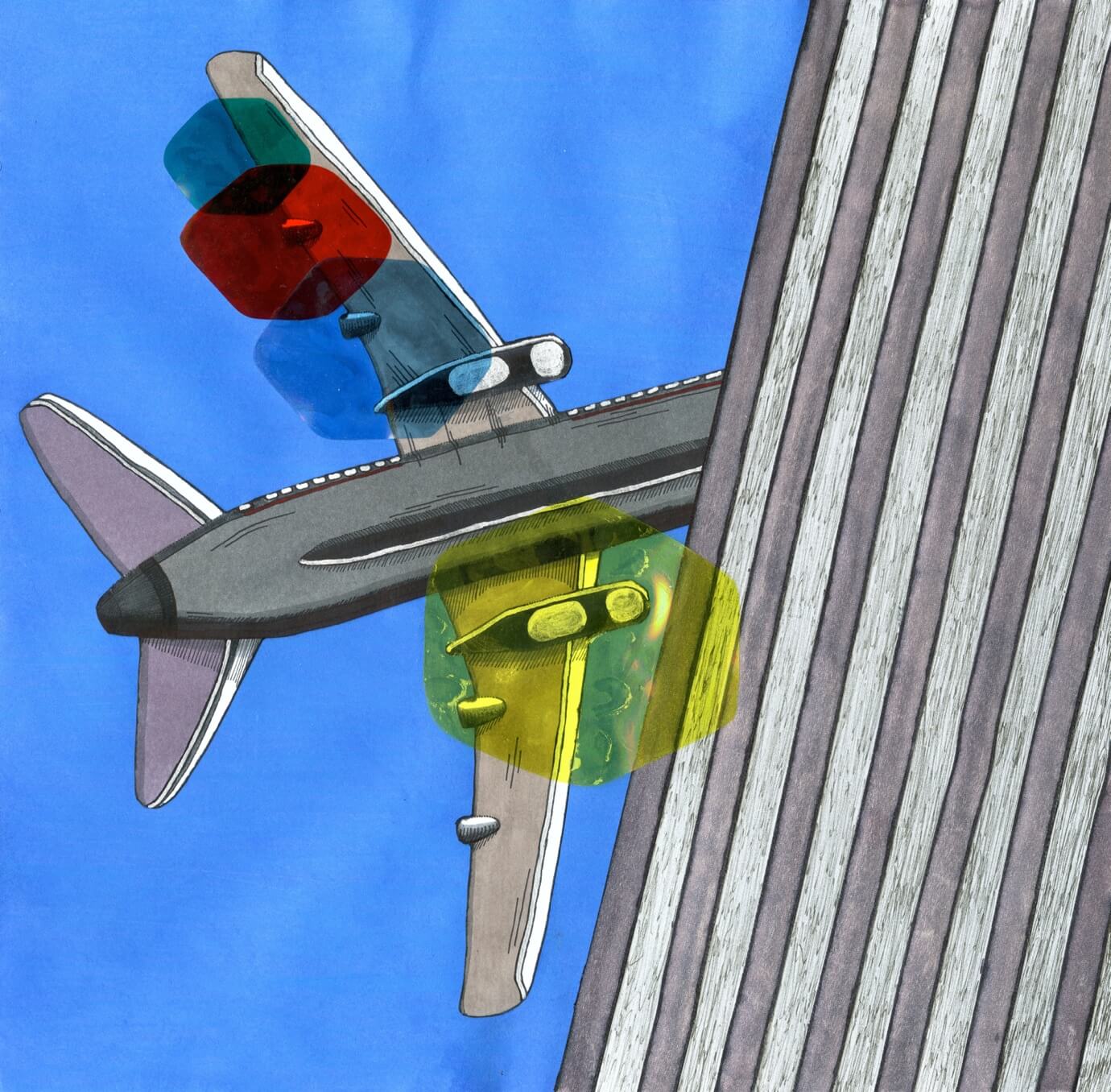

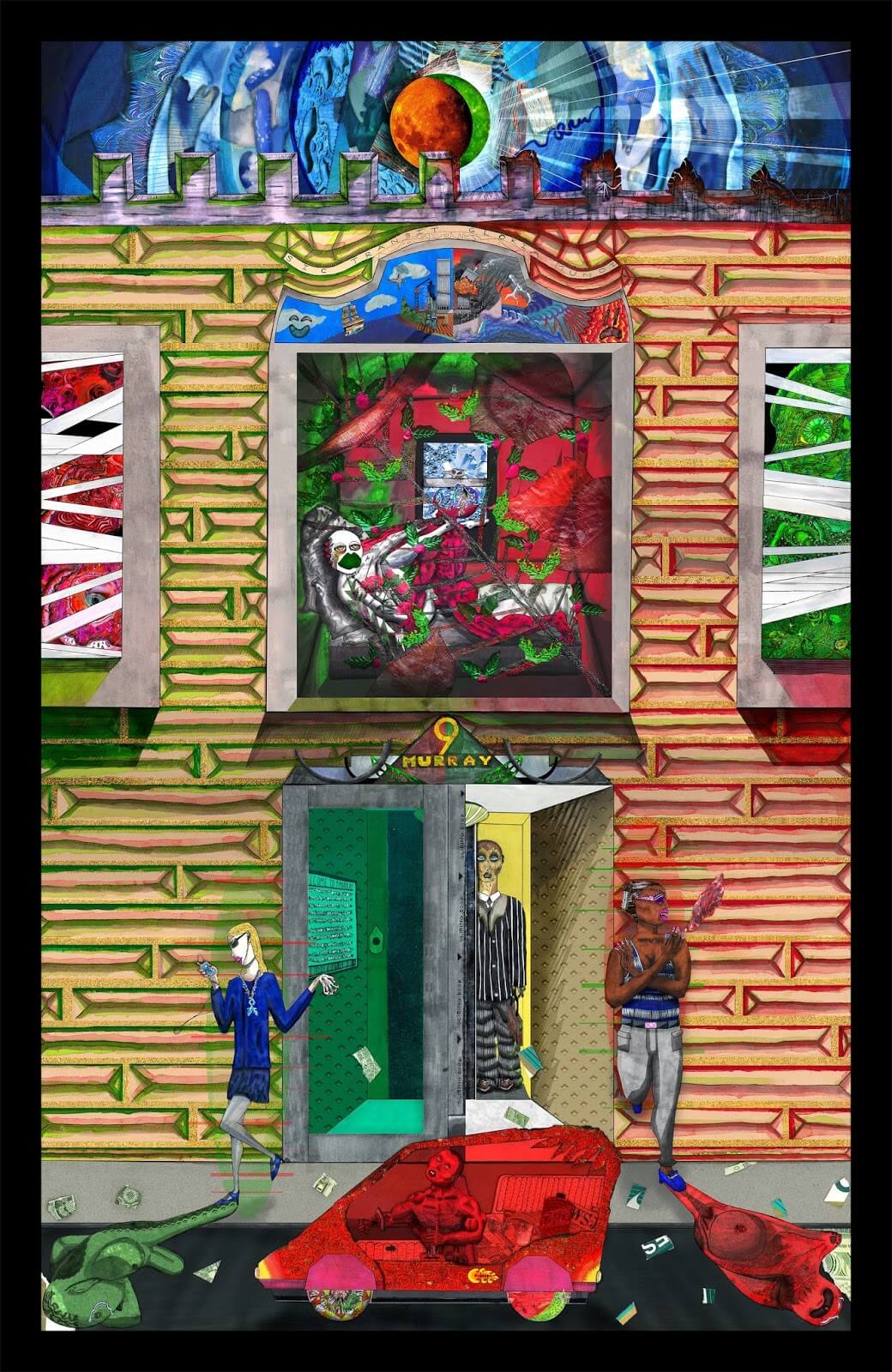

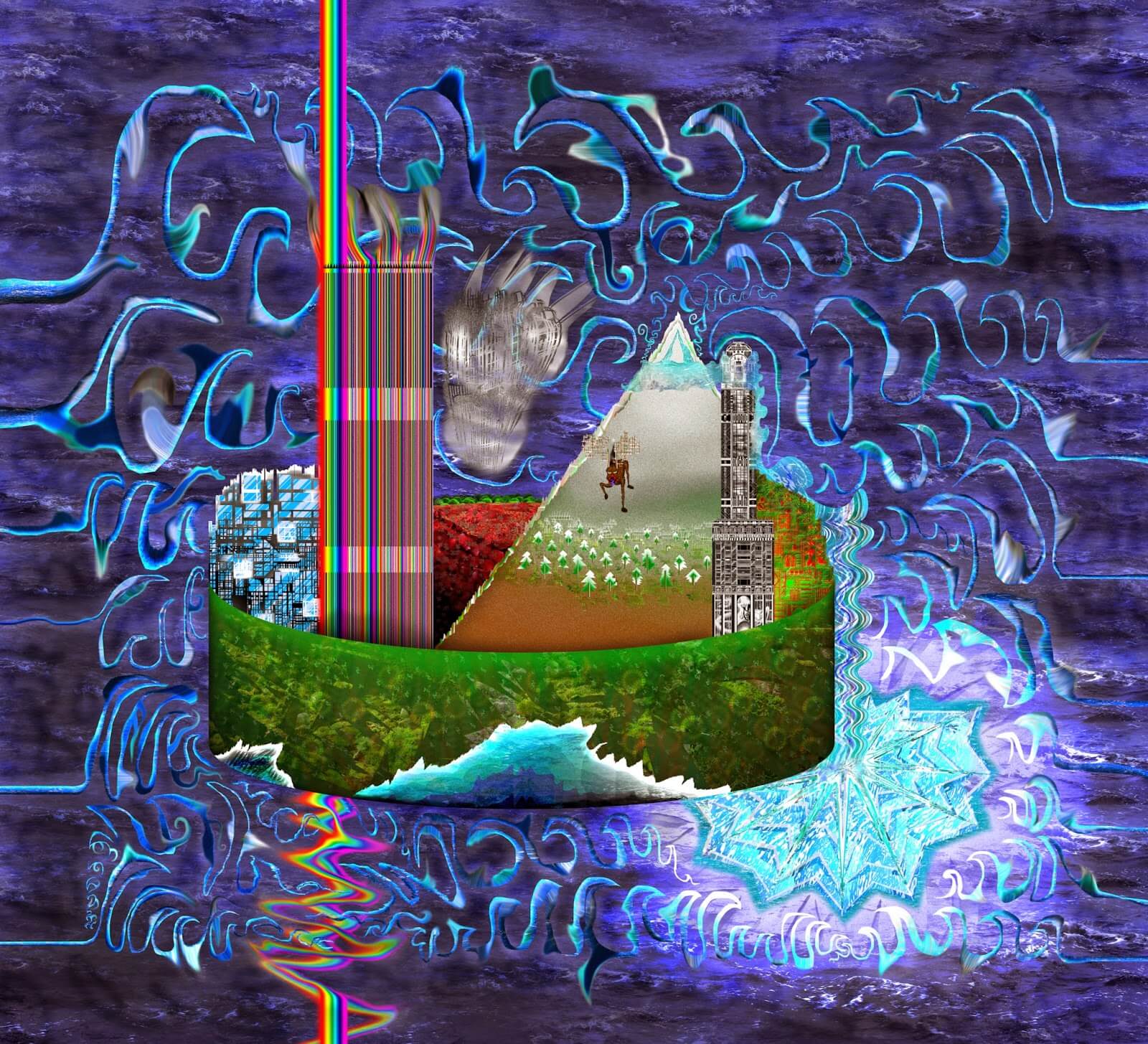

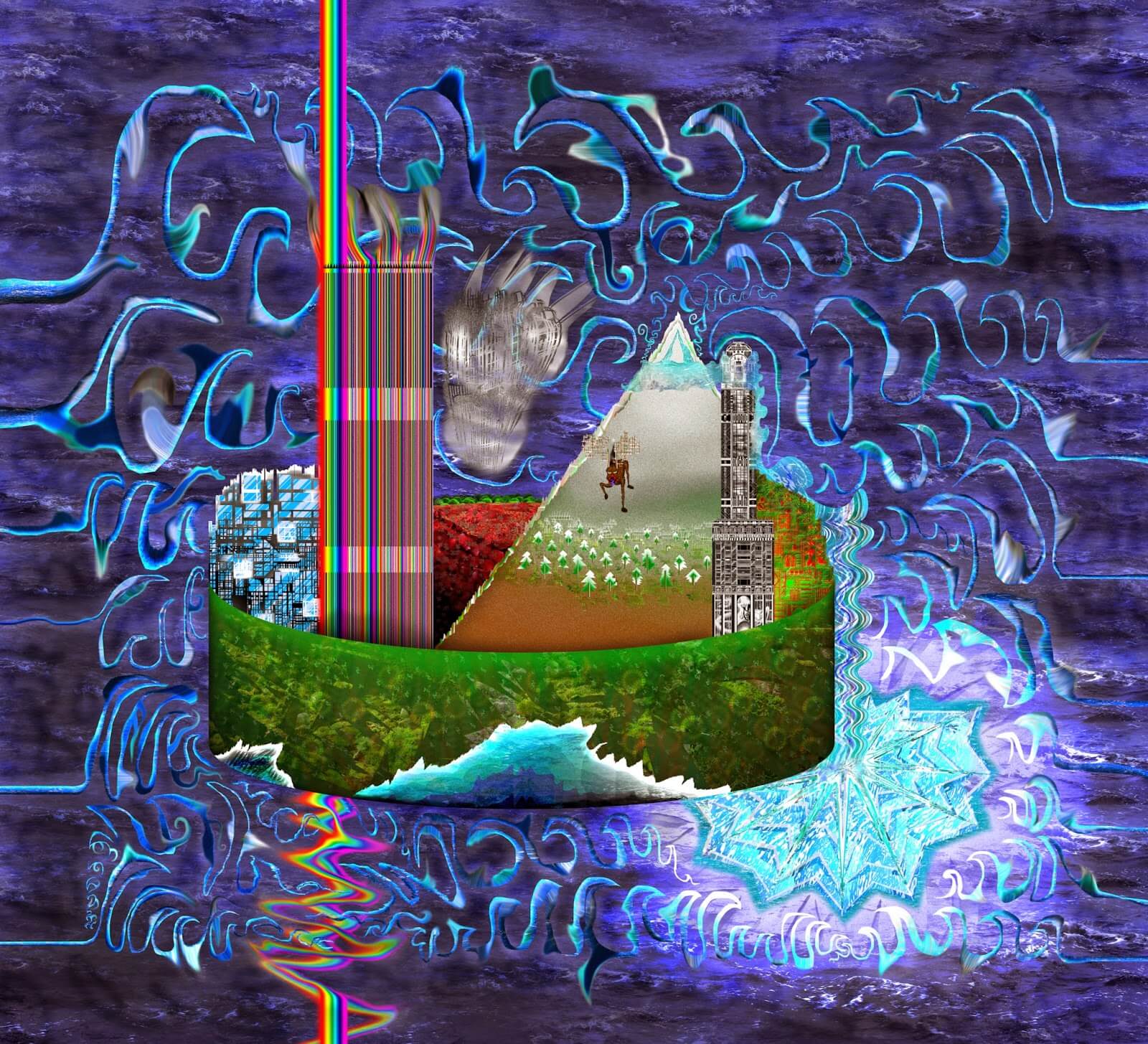

In the fourteen years since, imagery of the Twin Towers has become the central focus of Singer’s multimedia visual artwork, performance, and music composition. Instead of depicting the raw devastation of the events in realistic terms, he incorporates 9/11-related imagery into a vivid fantasy world; a dystopian, post-apocalyptic vision of New York City he calls “Barren Manhatta.” In Singer’s surreal hybrids of digital collage and magic marker drawings, what could feel like a hackneyed overuse of perhaps the most loaded visual symbol of this generation instead feels strange and new. It reads a bit like a child’s fairytale-informed understanding of an outsized tragedy.

Calder Kusmierski Singer in performance

Singer, who was named after modernist sculptor Alexander Calder, learned by example to turn to art-making when dealing with trauma: All three members of his immediate family are professional artists. His childhood TriBeCa home is overflowing with alienesque stuffed creatures in neon colors, with names like “Loose Lips” and “Screaming Mimi.” They’re the work of his mother, painter and children’s book illustrator Janet Kusmierski. His father, Greg Singer, also a painter, works at MoMA and runs Plutonian Pictures, a screening series, out of the family loft, the title’s implication being that he’s an alien from Pluto. His sister, Avery Singer, named for artist Milton Avery, makes massive airbrushed compositions that mash up vintage computer graphics with cubism. Her work was most recently shown in the New Museum Triennial.

A cartoonish large-lipped doll-boy features in many of Singer’s drawings. It’s a 2-D rendition of Singer’s performance alter ego, the freakish, Butoh dance-inspired My Little Daemon. In dance performances, scored with his own electronic alien-carnival-soundtrack compositions, Singer transforms himself into My Little Daemon with giant red glitter lips and skin painted powder-white. In “Rediscovering His Office,” his senior thesis performance at Oberlin College, My Little Daemon was cast as an office worker in a destroyed World Trade Center cubicle; in another performance, he was cast in a “twisted Christmas terrorland.”

Singer is one among a generation of artists responding to 9/11 in their work, much of which is now on view at the recently opened 9/11 Museum. His work was featured a pop-up show, Loft In The Red Zone, held at 23 Wall Street on the 9th anniversary of the attacks. “The space was formerly a bank lobby, eerily (and appropriately) covered in grey dust that brought to mind the fall-out from the fallen towers,” Singer says. Singer’s take is more fantastical and less reverential than most, since part of his intent is to “challenge the default perspective on the buildings,” he says. “Interpreted as ‘missed,’ many forget how oppressively the buildings hung on the skyline.”

We talked to Singer about his surreal vision of a dystopian abandoned New York City, his creative process, and coming of age in the wake of a national trauma.

How did the events of September 11th affect you as a middle schooler growing up in TriBeCa, and how do they continue to affect you?

Calder Singer: I grew up on Murray Street, a few blocks from the WTC site. The buildings were always there, oppressive and large. I did not feel much for them; they were among the many other tall, light-hogging high rises in Lower Manhattan. I was 11 years old and already uptown in middle school when the events unfurled. Sheltered in my school’s environment (and pre-cell phone), I had no idea what was actually going on. I heard that two small planes crashed into the towers, implying a minimal amount of damage & casualty. Oblivious to the reality, I was only excited to get out of school early. My parents and sister convened downtown before walking the 5 miles to the Upper East Side. We spent that night in the projection booth at MoMA (where my father was employed). I remember watching footage of the planes over and over. In the booth, it seemed like it was footage from a movie, maybe an art video that was being reviewed for the next day’s show. As days passed, the reality of the situation began to sink in, but it would be years until I could better empathize for the losses on that day.

What is the story of “Manhatta,” the recurring setting in a lot of your work, and who is the recurring character with the big glittery lips?

CS: All of these drawings are set in Manhattan. Some of these settings are truer to the actual locations, but more of them are set in a city dramatically re-imagined. It is a fantasia, a personalized reinterpretation of Manhattan as a mystical, surreal realm. In our actual world, the landmass of Manhattan has been heavily altered by man through the years. Think of Battery Park City: it is entirely built up from landfill (and from earth that was dug out for the original World Trade Center foundation). In some imperceptible future time, I imagine that the landmass of Manhatta has been smoothed and refined –– as it were a slow-evolving piece of sculpture, as if the Upper East Side had its way and rebuilt the whole island –– into one that extends endlessly north, its entire surface covered with white tiles (like the foam drop ceilings of office towers). It is a sterilized land, and it is haunted with spirits and memories from those who used to inhabit the city. It is thought of as a cursed place that one does not dare to go, haunted by the dark energies of desire, greed, and sorrow: the collective emotion of those who were present in Manhattan eons pat.

The characters differ in each piece, but revolve primarily around an androgynous, large-lipped doll-boy. He is something of a self-portrait, a cartoonified rendition of how I present myself in performance. He is our protagonist in this distorted future. We gather insight into his life and this place through some of these drawings.

CS: Ideas come from all places, but mostly through day-dreaming. The potent imagery of the WTC has been stirring in my mind since high school. I think of it as an empty fish tank filled with a few objects; there are endless ways to arrange the objects inside; I want to explore the possibilities.

CS: One thing is for certain: I’ve been infected with the now unavoidable symbolism of the Twin Towers. What were once two boxy, sun-hogging, unloved buildings have now become direct metaphors for patriotism, tragedy, and destruction. Like two steel rods that wound through the thousands of layers and hundreds of floors of the Twin Towers, the WTC and attacks of 9/11/2001 seem to be a touchpoint for most humans on earth. Invocations of the Twin Towers (images, words) stir connotations at the crossroads of many dark tropes: death, corrupt politics, American innocence lost (something we never had), misplaced hatred, the karmic retribution of backward economic systems, the shifting frontier of modernization, the fragility of everything (even that which seems unbreakable). I want to explore various contextualizations of the Towers, subverting the ways they are understood, misunderstood, and overly-worshipped.

Suddenly, I lived three blocks from one of the most talked about places in the world: Ground Zero. I felt I had to tie myself to them; many seemed to have that need. Ultimately, the Towers became a touchpoint for my own darkness and moods, although (all in all) I experienced little sorrow over the events themselves at the time. They ushered out my feelings of loneliness, isolation, romantic disappointment, and the chills of post-modern city living. I want also to challenge the perspectives of the buildings. Interpreted as “missed”, many forget how oppressively the buildings hung on the skyline.

“Governor’s Island,” 2010

You might also like