Inspired by Judy Chicago, Female Inmates Turn Trauma Into Art

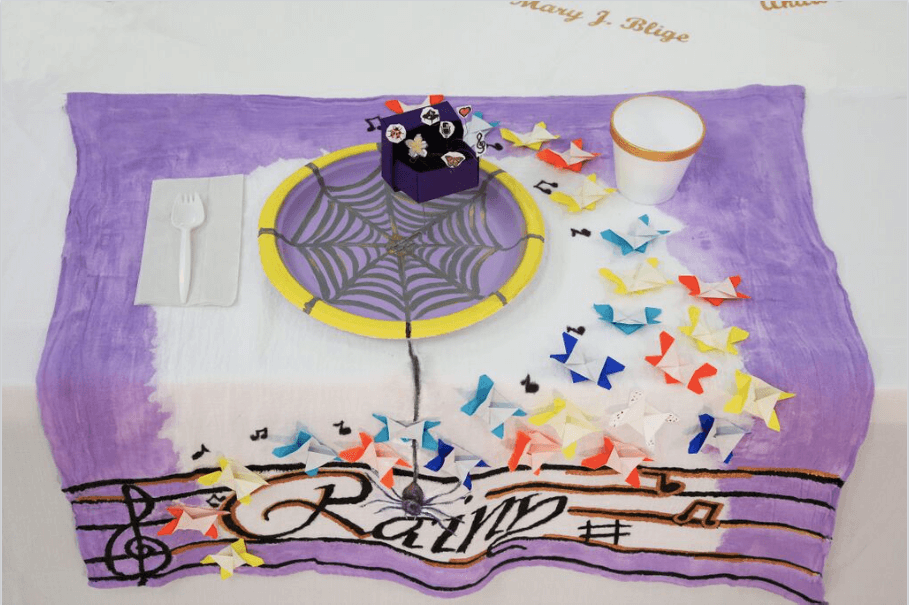

From “Shared Dining,” by Lisette Oblitas-Cruz, honoring Phyllis Porter, a woman who died in a car accident Oblitas-Cruz caused.

Paper plates, plastic cutlery, and cut-out Bible pages were among the meager selection of art supplies provided to the Women of York, a group of 10 inmates at York Correctional Facility, in an art program run by historian and activist Dr. Elizabeth Sackler. But the women were resourceful enough to transform these materials into powerful reinterpretations of Judy Chicago’s epic feminist artwork, “The Dinner Party.“

The Women of York’s final group project, “Shared Dining,” is now on view at the Brooklyn Museum alongside “The Dinner Party,” which has been installed there since 1997. Only a couple of the Women of York will get to see it the exhibit in person, though, before it’s taken down in September.

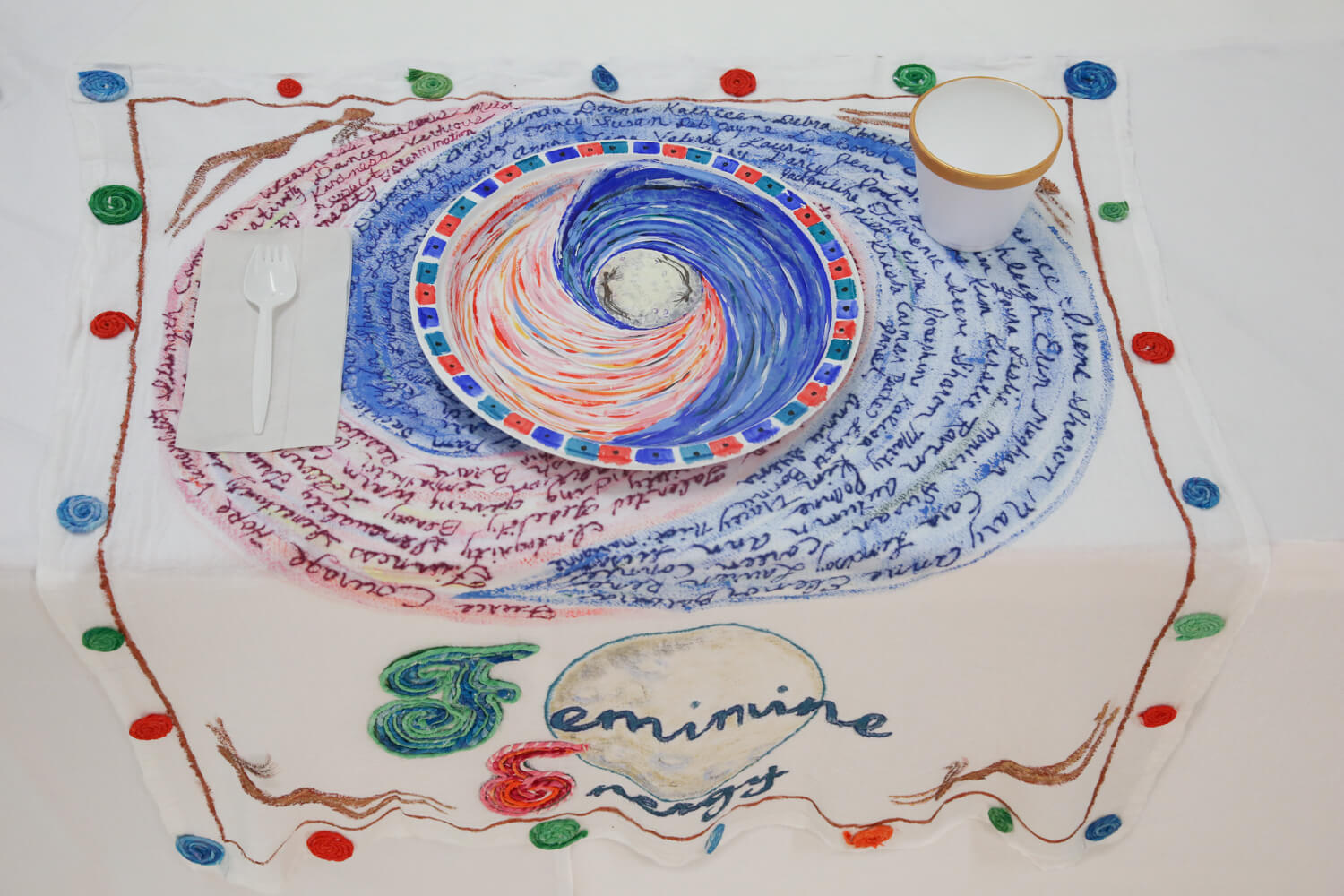

Inspired by Chicago’s work, which features ornate table settings for 39 influential women from history and mythology, the Women of York each created a place setting that honors a female figure who inspires them, from Malala Yousefzai to a great aunt. Over the course of six months, in a prison library workshop, they turned styrofoam cups into gold-painted chalices, cardboard and carved soap into silverware, and Bible pages into origami flowers.

Amid the nationwide scourge of mass incarceration, the artists’ testimonials and the power of their creations make a strong case for art programs in prisons. “It was a form of therapy,” Lisette Oblitas-Cruz, one of the Women of York, says in a phone interview. “Every time I grabbed that brush and mixed some colors, it was like escape for me, I was no longer in prison.”

A table setting honoring Malala Yousefzai, activist and youngest-ever Nobel Prize Laureate

Oblitas-Cruz, now 34, created one of the most compelling works in “Shared Dining.” It honors Phyllis Porter, a 77-year-old former florist who died in the 2009 car crash that Oblitas-Cruz caused while using her cell phone driving home from Mohegan Sun. Oblitas-Cruz was sentenced to four and a half years in prison for misconduct with a motor vehicle and a DUI, and was released one year ago.

“I knew instantly who I would honor in this project,” Oblitas-Cruz says. She was “humbled” when Ms. Porter’s two daughters publicly forgave her at the court hearing, telling her, “All humans make mistakes.” One daughter continued to write letters to Oblitas-Cruz while she was in prison, urging her to forgive herself. “It was a gift,” Oblitas-Cruz, who immigrated to the U.S. from Lima, Peru at age 17, says. “The apple doesn’t fall far from the tree, so who would I be thankful for but for Ms. Porter herself?”

Oblitas-Cruz says the only times she felt “free of pain and guilt” in prison was while she was working on the “Shared Dining” project. On a paper plate, she painted Ms. Porter’s “motherly, guardian angel” eye from a photograph. She adorned the place setting with references to the former florist’s love of music. The creation process wasn’t easy, but it was ultimately “healing,” Oblitas-Cruz says. “We were our own worst judges. We’d look at our placemats and say, ‘How do I make this art piece happen? Does this look good?’ But we empowered each other, and there was a sense of sisterhood, which was so unlikely in prison. You usually have to wear a mask, otherwise people walk all over you.”

Oblitas-Cruz laments that more prisons don’t have similar art programs. Of the 1,000 inmates housed at York, in Connecticut, only ten were able to participate in the Shared Dining project. Now back at her former job as a nanny, she hopes to get involved with prison reform movements and potentially go back to York to teach art to inmates.

“It’s a compelling story about someone who’s trying to process a traumatic event,” curatorial assistant Stefanie Weissberg says. “It certainly speaks to power of art for rehabilitation and processing crimes.”

“It’s a great supplement to The Dinner Party,” Weissberg says of “Shared Dining.” “It speaks to the multiplicity of stories that can continue to be told, not just of women who were historically and canonically famous enough to be researched by Judy Chicago, but also women who maybe are lesser known, but significant to individual people.” In addition to Phyllis Porter, the women honored here include mothers, the Virgin Mary, famed Nascar driver Danica Patrick, and Malala Yousafzai, the Pakistani activist for female education and the youngest-ever Nobel Prize laureate.

“We were moved to honor the women who have touched our lives,” the artists, most of whom chose to be identified only by their first names, explained in a statement. “Our plates represent their strength, struggles, courage and achievements. These women are models of who we aspire to be. We have not been limited by the lack of resources; our imagination and creativity allowed us to turn commonplace objects into art.”

Perhaps the best example of this resourcefulness: The Women of York wanted to crochet, but weren’t allowed to use needles. So, instead, they crocheted with staples, making red and green rosettes and ornate yarn borders for their table settings. You’d never know the difference.

Women of York: “Shared Dining,” a Collaborative Project Created by Incarcerated Women, is on view at the Brooklyn Museum through September 13, 2015, in the Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art’s Herstory Gallery.

All photos courtesy The Brooklyn Museum.

You might also like