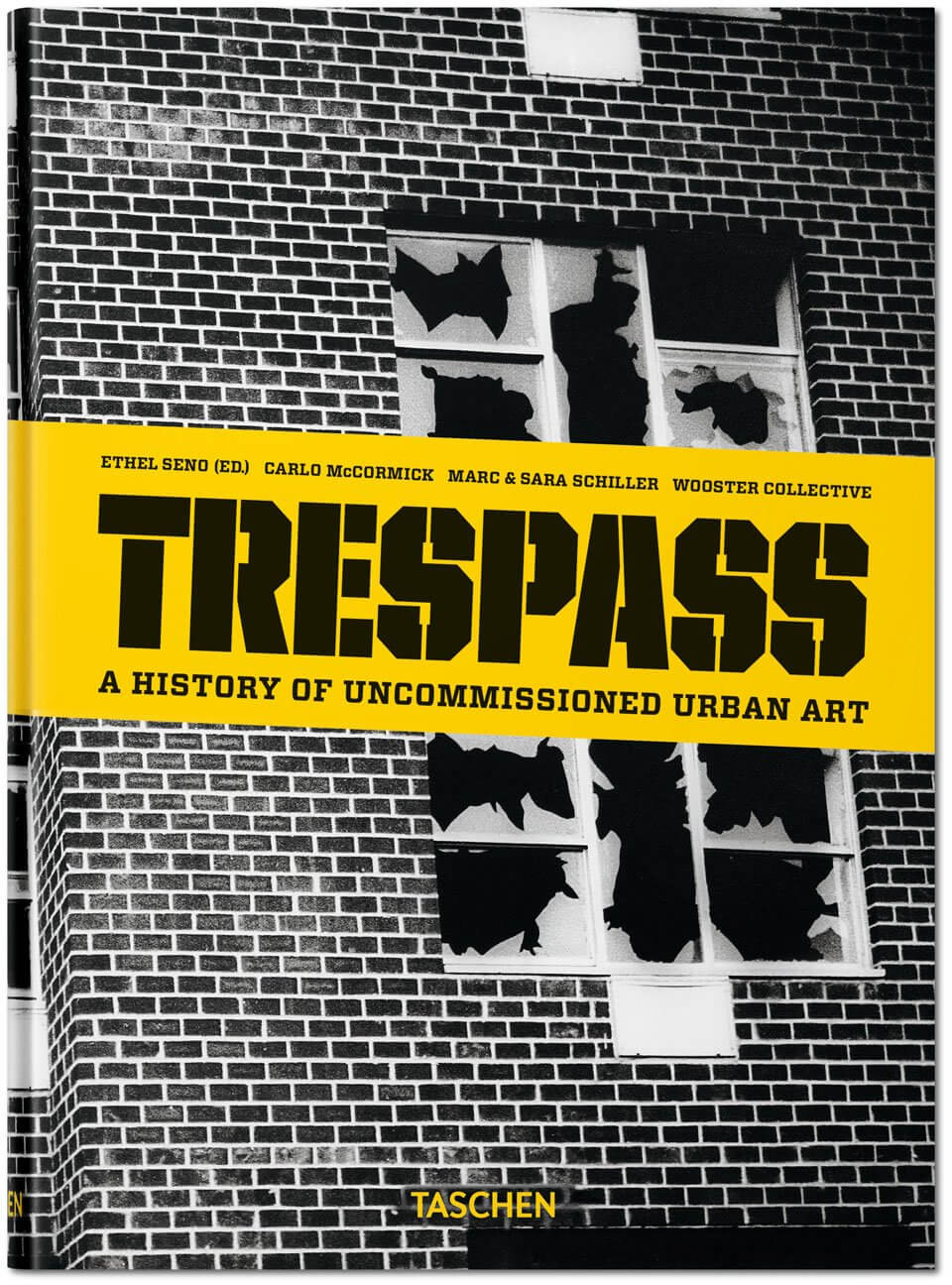

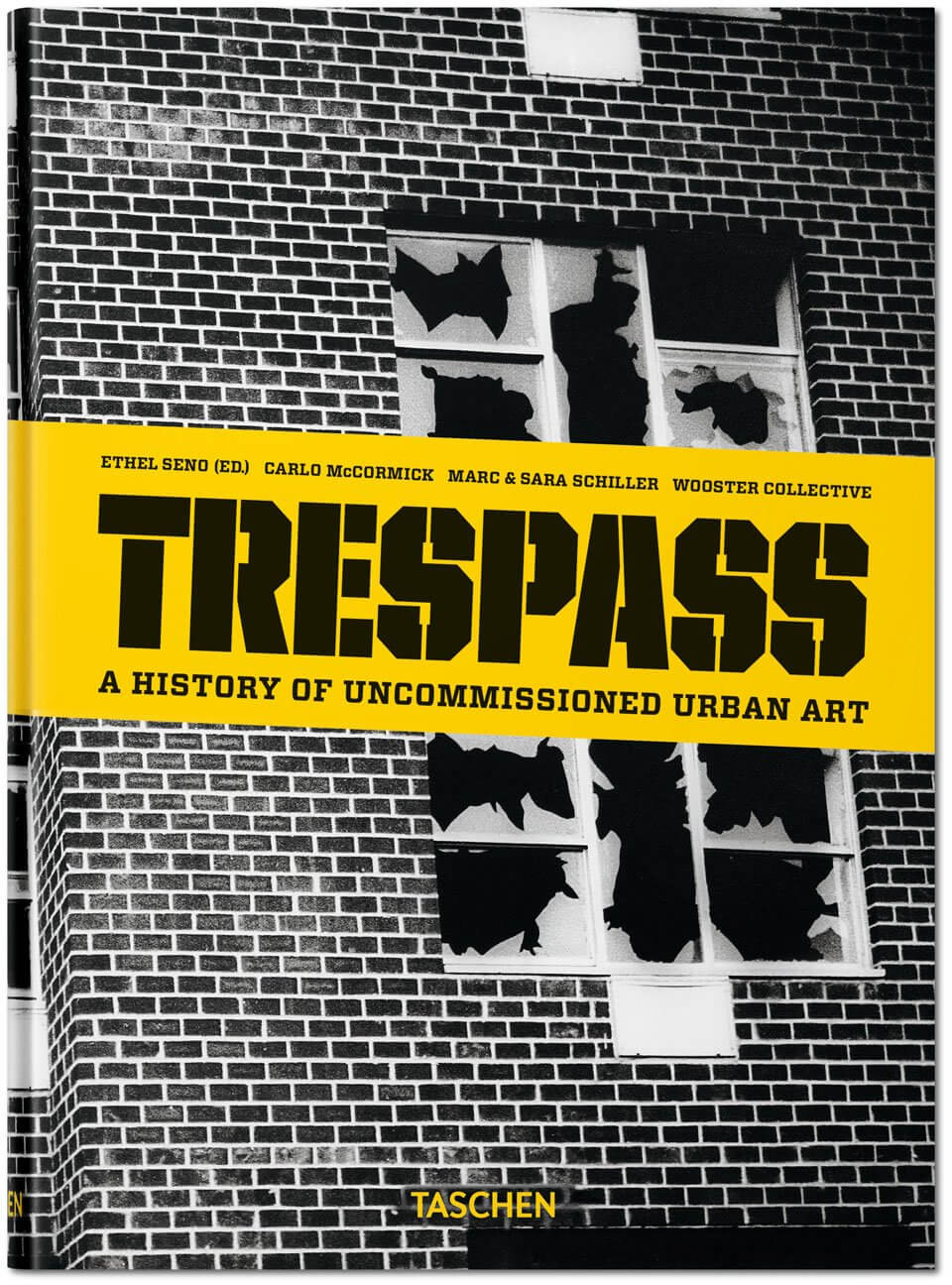

A Brief Visual History of Uncommissioned Street Art

During the rise of New York City’s graffiti culture in the crime-ridden 70s, spraypaint-wielding kids were considered vandals by much of the mainstream, their public art thought not much better than public urination. Now, though, the best contemporary graffiti writers are recognized for what they are–artists–and many, from Banksy to KAWS to Shepherd Fairey, have even won over the Ivory Towered fine art establishment. Trespass: A History of Uncommissioned Urban Art, by Wooster Collective founders Marc and Sarah Schiller, offers a visually stunning, in-depth look through generations of art found on mailboxes, billboards, pavement, buildings–basically, everywhere but behind museum walls.

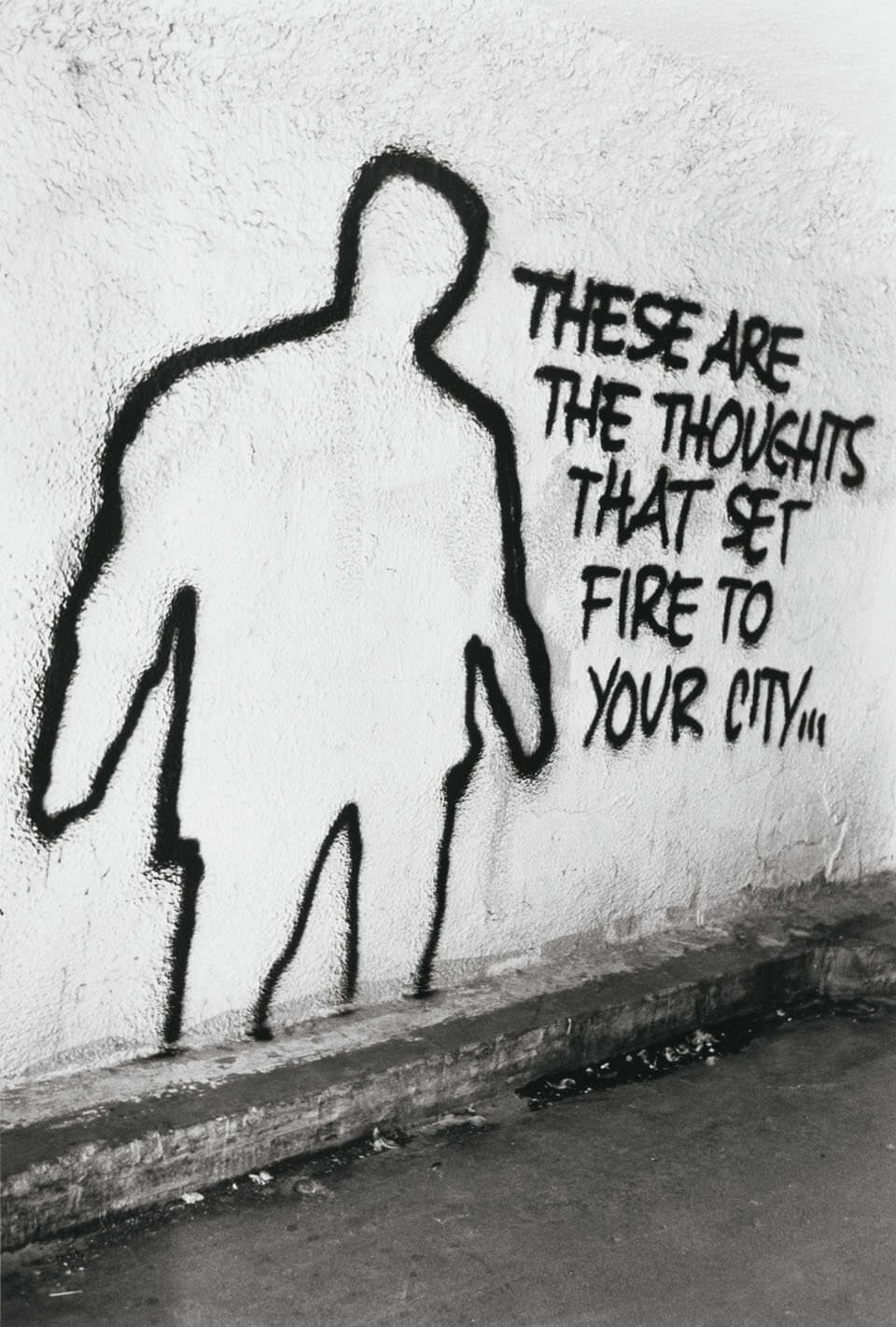

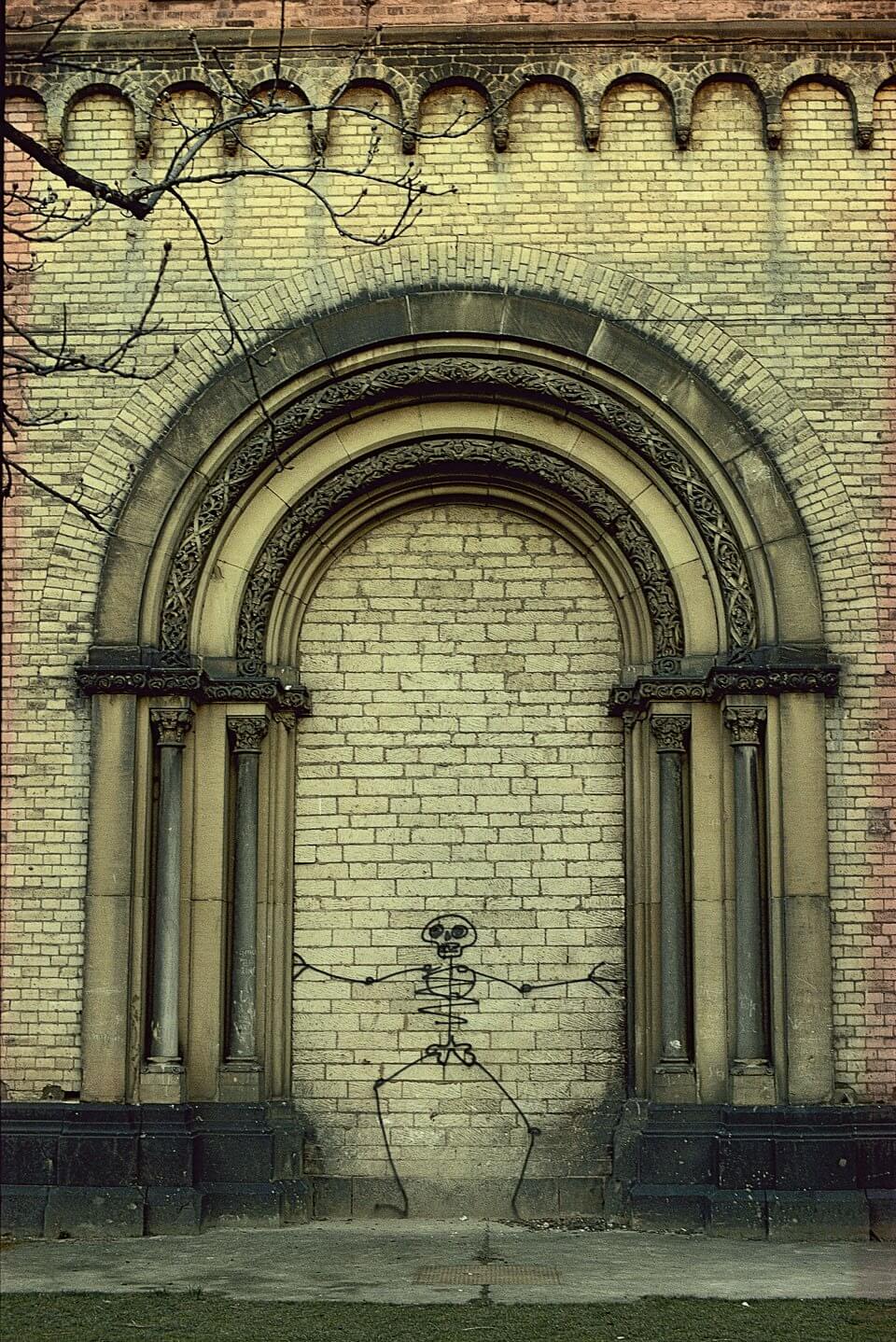

The urban canvases featured range from the irreverently sacrilegious (a silhouette of the Mona Lisa mooning passersby from a brick wall) to the political (a doctored London tube sign that reads “Mind the Income Gap”). And it’s the political elements of street art–its championing of freedom of speech in defiance of the law–that resonate most powerfully throughout Trespass. Ultimately, the images’ collective visual power makes a strong case for slackening draconian anti-graffiti laws, which tend to equate all uncommissioned public art, no matter how technically impressive, with vandalism. As Banksy writes in the preface:

To some people breaking into property and painting it might seem a little inconsiderate, but in reality the 30 square centimeters of your brain are trespassed upon every day by teams of marketing experts. Graffiti is a perfectly proportionate response to being sold unattainable goals by a society obsessed with status and infamy. Graffiti is the sight of an unregulated free market getting the kind of art it deserves. And although some people might say it’s all a big waste of time, no one cares about their opinion if their name isn’t written in huge letters on the bridge into town.

It’s largely thanks to street artists that the imagery dominating our cityscapes isn’t limited to a monotonous mosaic of photoshopped advertisements. But what would it take for lawmakers to take this into account, when state legislatures criminalizing graffiti make no distinctions with regards to artistic quality, instead broadly deeming all of it “visual pollution” and a “public nuisance?” One typical San Francisco Public Works Code article states that “graffiti is detrimental to the health, safety, and welfare of the community in that it promotes a perception in the community that the laws protecting public and private property can be disregarded with impunity.” New York legislature declares that “graffiti presents the image of a deteriorating community… [it’s] an assault upon individual sensibilities.” And sure, not every paint marker squiggle on a telephone pole qualifies as “art.” Still, the writers of Trespass make the case that this legislative perspective is damaging and alarmist, not to mention very costly–graffiti eradication efforts cost the nation $4 billion to $5 billion a year, and often to no avail, as graffiti endures.

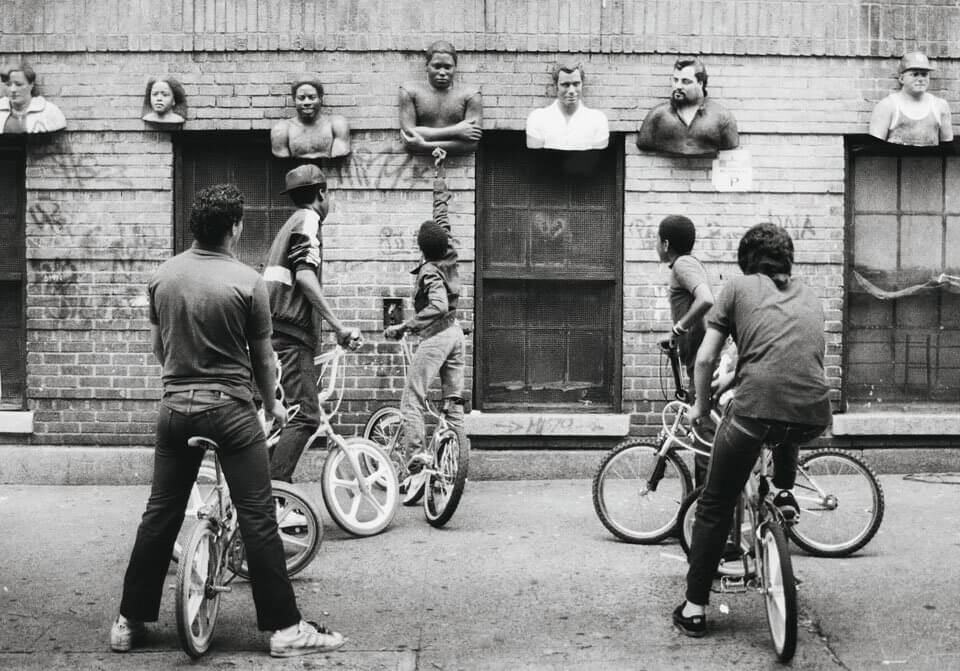

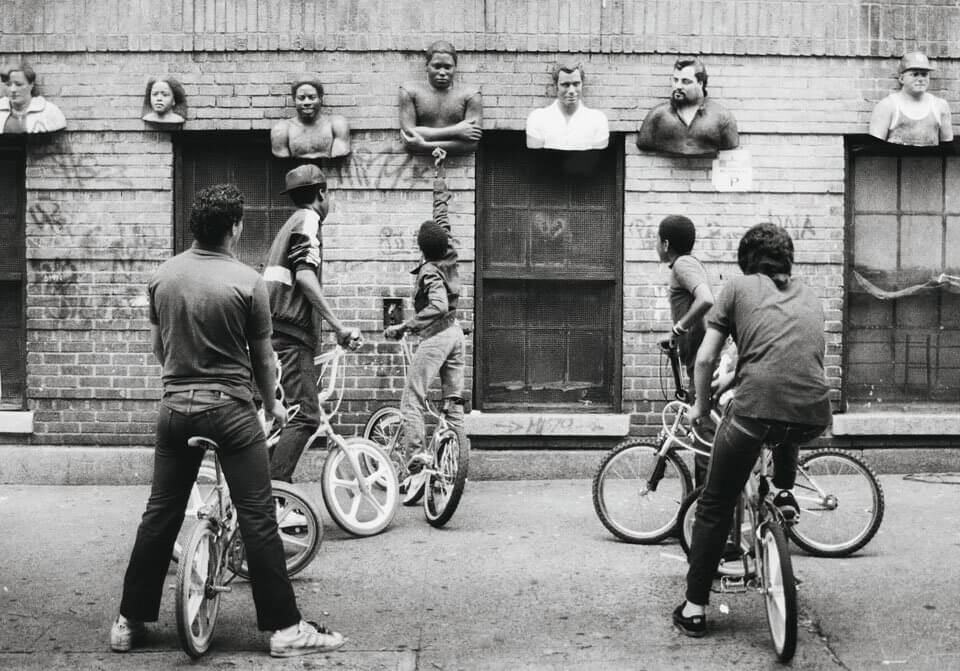

John Ahearn, Walton Ave, Bronx, NYC, 1985

“Outlawing graffiti is not an effective solution,” writes J. Tony Serra in the book. “All subcultures that feel in any way repressed by the dominant culture find an avenue by which to manifest their artistic creativity and their protest mentality. Graffiti is an outcome of psychological, intellectual, social, and political needs of a subculture, and broadly speaking, it is a symbol of the dissent by a minority faced with multiple forms of First Amendment repression.”

Such dissent has inspired the work of giants in the genre like Keith Haring, Swoon, Jean-Michel Basquiat, Blu, Jenny Holzer, and Barbara Kruger, as well as their lesser-known contemporaries, who are featured here next to their ancient counterparts (the anonymous creators of Egypt’s Sphinx, for example). “In equating all graffiti with vandalism, statutes and policies ignore the fact that graffiti and vandalism are not mutually inclusive,” Serra writes. If the distinction were drawn more clearly, both in the laws and by the art community, fewer artists would end up unnecessarily criminalized, and their art could be properly celebrated.

[metaslider id=33129]

Here, image highlights from Trespass.

Duke Riley, After the Battle of Brooklyn, East River, NYC, 2007. Copyright The New York Times/Redux/Laif

Recently rereleased in a Reader’s Edition from art book powerhouse Taschen, Trespass: A History of Uncommissioned Urban Art is available for $30.

Follow Carey Dunne on Twitter @CareyDunne

You might also like