Brooklyn Music Factory: How the Next Generation of Brooklyn Musicians Found a Home in Gowanus

Big City Country

photos by Jean Bourbon, courtesy of the Brooklyn Music Factory

Last Saturday, two 12-year-olds sat talking at a picnic table inside the Brooklyn Music Factory—a music school for kids and the whole family—which occupies an old sun-filled soap factory in industrial Gowanus.

“What’s your name?” I asked the first.

“Jude, like the song,” replied Jude Rollison, who plays guitar and sings for a country cover band, Big City Country.

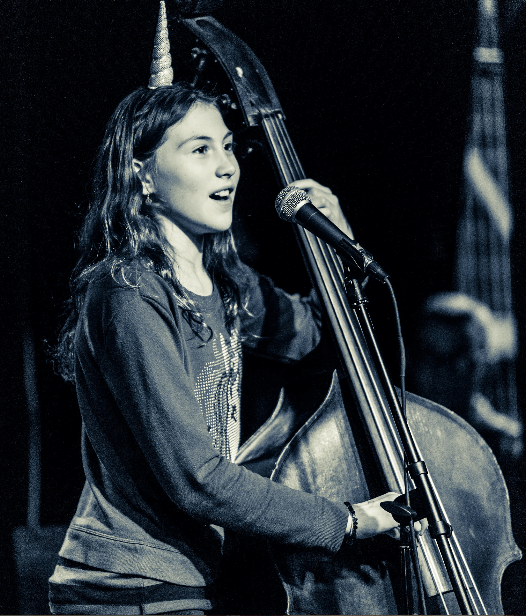

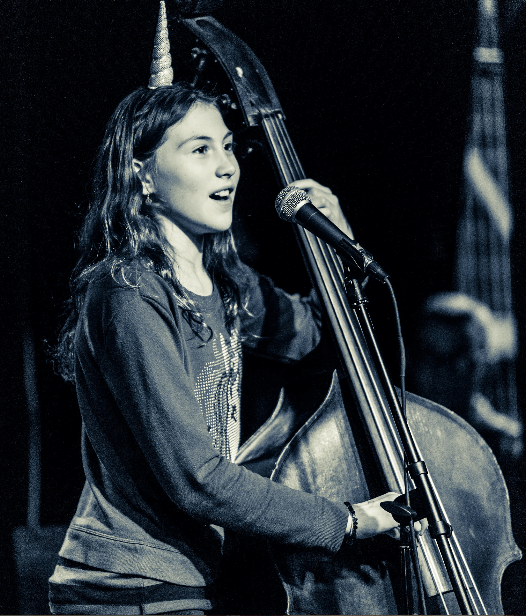

“I’m Grace, like the song,” replied Grace Isaacs, an upright bass player, pianist, and singer.

“Like the song!” Both girls giggled.

“Like the song?” I asked.

“Amaaazing graace… ” they sang in response.

Jude and Grace were waiting with their band teacher, Nikolaus Schuhbeck, for their drummer, 12-year-old Eoin Riley-Duffy.

“If Eoin doesn’t come, can we just do duets or something?” Jude pleaded.

“Yeah,” Nik said. “You can write a set list or something.”

The girls celebrated. “Yay!”

“Eoin always looks so snazzy,” Jude assessed enviously. “I’m like, where are my outfit goals? He always has a tie on. I can’t even put on a tie.”

Eoin appeared a few minutes later in the doorway wearing shorts, a yellow t-shirt, and—hanging loosely around his neck—a fat tie covered in blue polka dots.

“Eoin!” rejoiced the girls.

“Eoin, what’s happening?” Nik asked, checking in.

The group migrated to the band room. It was a big practice. The following Friday they would perform in a release show at the school for a CD of their music, along with the four other advanced bands at the music school. Eoin’s expression was placid, but in a way that made you believe he could handle whatever he needed to. The girls raced ahead and sang together in a mock country twang, already in harmony.

Remember when you were a kid and the way in which sitting alone in a room with your music teacher and struggling through scales felt like punishment? I do too. And probably that’s why today I have no musical ability whatsoever.

But what if it had been fun? What if becoming a good musician just meant hanging out with your friends, but with instruments in your hands?

That might sound like magical thinking, but it is precisely what is happening at Brooklyn Music Factory, a five-year-old music school for the whole family that is churning out dozens of precocious kid musicians and bands. On demand, students can crank out a chilling cover of an old country song or a nuanced track of their own and make it look like child’s play.

Of course, the beauty of it, is that it literally is child’s play—and the fact that it’s children playing is also what makes the music come to life. Because despite the fact that students get thorough technical training, the reason they get so excited to practice twice a week—even after a long school day—is that they get to do it with friends.

Last Friday, like old pros, Big City Country delivered “countrified” rock songs and current pop music (like “These Boots were Made for Walking,” on one hand, and Beyoncé’s “Halo,” on the other) with a sped-up country train beat, an upright bass, and sweet harmonies. They also played an original track, “Stuck on You,” which is not only catchy, but also pumped full of emotionally advanced lyrics that sound like they came from a late-stage teenager rather than a group of tweens. And when you look at them and are reminded that they are still just 12, you start to feel real pangs of regret that you did not join a band with your friends when you were seven, too.

Sure enough, that longing for what music education could have been, and should ideally be, led to the start of Brooklyn Music Factory. Co-founders Peira Moinester and Nate Shaw had each been disappointed by overly formal and physically isolated experiences learning and teaching music.

Peira grew up on Third Street in Brooklyn, not so far from the school, and wanted to sing. “I took boring singing lessons and piano lessons and sang opera at the Brooklyn Conservatory of Music,” she explained. On her own time, she played in rock bands. After college she got into toddler music education in Brooklyn public schools, but eventually there were budget cuts. “I was like, ‘What was I going to do?’ Open something I would have wanted when I was a kid.”

Around the same time, Nate Shaw–who had toured with bands and been a jazz musician in the city for most of his adult life–wanted to see his kids more and make money at the same time, so he built a basement studio where he could write music for TV shows and movies. But the schedule was grueling and wore him down; meanwhile, he saw his family even less. “I got in so deep (into scoring) that I hit a dark space personally. I was working ten and twelve hours a day, producing music and not really actually seeing my kids at all because I was working all the time.” On top of that, it took away the part of music making that he enjoyed most: playing it with other people.

So he started teaching again. But he realized he needed to tweak the system. “Part of what I didn’t like about teaching private lessons was that it was a solitary thing. One student came in, another left, and no matter how much I tried to introduce them to one another and get gigs with students and rent a jazz club, which parents loved, that wasn’t the point: the point was I wanted these kids to get to know each other.” And because he had kids of his own this time, he became fixated on the process of learning–how to effectively communicate information to kids so that they would come back each week with what they learned, curious and self-motivated.

When he boiled the process down to the essentials, there were two key ingredients: community and fun.

At the same time, Peira (who had already begun her own school called Brooklyn Kids Rock) and Nate were running in the same music circles, and found they shared the same philosophy about music education.

“Nate said, ‘Let’s just do this together. Our mission is about process, and keeping it fun. Kids are motivated by fun and community. Let’s put them together,” Peira recalled.

Certainly–and more than ever–there are music schools for kids that focus on creating bands, and putting on shows. School of Rock, on the very same block, is one of them. But, Peira explained, the focus is usually about making rock stars, not musicians. “I don’t care if they play around the campfire, I just want them to be musicians for life. And if that means making music with your family, then that’s cool.”

The curriculum at Brooklyn Music factory follows a student’s entire childhood, from ages 4 to 17, and all of it is built around games. Band classes start out with a drum circle, then progress to movement games, and culminate on the bandstand. From the get go, kids are challenged to be creative and improvise, in private lessons and with their bands. As they age, the hope is that that kind of elastic thinking evolves into songwriting. Next year, Big City Country will write and record an entire album of original music.

The school doesn’t have an official headcount. It keeps tabs on the number of student families instead–kids and parents included. The current number is 220 families; in the fall there will be room for 280, a couple hundred private lessons, and 39 bands (which includes a number of adult bands, too). “[Big City Country’s drummer] Eoin is the perfect example–his whole family is just thriving here,” Peira pointed out.

“To us, you’re educating the whole family,” said Nate. “The paradigm shift is not measuring what level of book you get through or how many hours you practice, but by the number of gigs that students play with one another. Ultimately, music is a social art form.”

And that goal–getting kids together to learn from and challenge each other–was the original idea behind Big City Country. The fact that it was country was beside the point. Nate had been doing a gig at a place called Rodeo Bar, where he became more familiar with people like Hank Williams and Johnny Cash. “[The kids] think they care about aesthetics but they really don’t. They don’t need to dictate the music as much as they think they do,” said Nate. So for two years, the band played country covers and nothing else.

But as hoped, they evolved. Now the group makes their own arrangements of basically anything. “The core of that group has been together for three or four years, and amazing things happen with kids that are able to stay the course in terms of being in something together,” said Nate. “It’s an ass-kicker to learn how to play an instrument and sing and work with a band, but if you do it in a communal way, a magical level of confidence starts to grow. Of course, an eleven-year-old girl doesn’t put it in those terms, but they know that something bigger is happening. And that’s what you witness in [Big City Country].”

In the practice space, Jude, Grace, and Eoin (who were two band members short without Bella and Ruby, who also sing and play keys and guitar) were getting ready to run through their CD release set. Grace thumped on her bass, Jude strummed her electric guitar like it was an extension of her hand, and Eoin sat behind the drum set. His head just poked out from behind the symbols. Grace had jotted down a set list on her phone that they would follow.

They started with an upbeat cover that sounded like something Johnny Cash and June Carter might have belted out together in energized harmony. But it wasn’t that at all. It was seventeen-year-old pop singer Lorde’s mega-hit from a couple of years ago, “Royals.” But the arrangement was so expert that, as far as I’m concerned, it far surpassed the original.

The girls, between songs, laughed and chatted and usually sang a melodramatic verse from the song that was about to follow. Eoin stayed behind the drums and kept cool.

An assistant teacher, Jack, asked Jude to describe the tempo of the next song, the pretty—and pretty dark—Dolly Parton number “Jolene.” Eoin followed with three drum taps to start the beat. Jude entered deep and soulfully. “Jolene, Jolene, Jolene, Joleeeene, I’m begging of you please don’t take my maaaan.”

Jude was no longer Jude the 12-year-old with sneakers and braces. That Jude was somewhere else. Instead she became a conduit for this deeply moving music. Grace joined with a simple bass progression, followed by Eoin on the drums. As the verse continued, Grace added a delicate harmony, which was pitch perfect and brought the song to another emotional place. There was a symbol brush, and Jude finished, “Please don’t take him just because you caaaan.”

“See, one of the things that is so great about them is that half of the band is missing, but you wouldn’t even know it,” Nik commented. “They’ve been together as a band for at least four years. They’re a real band.”

Every time they finished a song, there was a jolt back to reality–mainly to the fact that, once again, it was a bunch of kids who had brought you to an emotionally complex space that they themselves have likely not experienced. It’s a thrill to see any kid do something well; but to see a group of them working together, doing something better than most adults will ever do, while still unselfconscious of themselves, is a power of its own.

At one point during the song “These Boots Were Made For Walking,” there was a slightly off-beat transition. It was confusing because all I had been aware of was that I was listening to a song I’d heard on the radio countless times. So when the rough patch arrived, and I saw Jude’s big bracey smile, and Grace’s polka dot socks and Converse sneakers, and Eoin, mostly hidden by his own instrument, there was a cognitive dissonance between where I had been in my head and what I saw in front of me.

“That was really great, guys,” Nik commented.

They finished their set with their original, “Stuck With You.” Catchy and rich with compelling harmony, a rock-and-roll beat, and filled again with surprisingly advanced lyrics, the song had me bopping my head along with them, and feeling good. It made me reflect on what was so fantastic about them, how they are a band, and how they can’t imagine not making music with each other. Which means that, even more excitingly, they still have so much further they can go, and only time to get there together. And how the way they feel as a band—and how audiences feel watching and hearing them perform—was an extension of how all the kids and families at Brooklyn Music Factory might feel. This, anyway, was what I was thinking before being brought out of my reverie rather abruptly by the end of the tune.

“That is the driest song we’ve ever played,” Jude said into the microphone, deadpan, as soon as it ended; mic drop accomplished.

You might also like