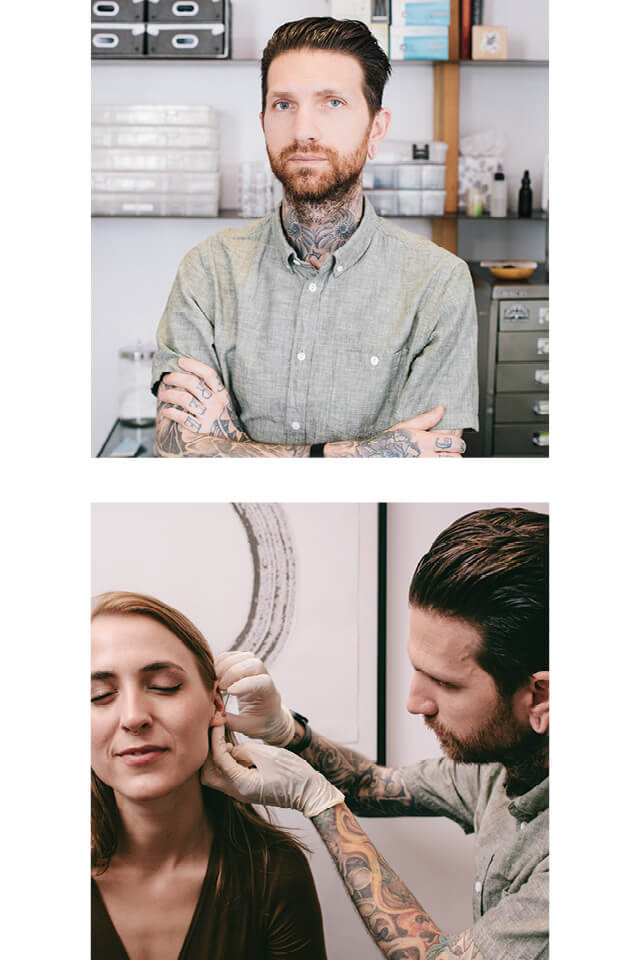

The Doctor is In: Why J. Colby Smith Is the Best Piercer in New York

Photos by Daniel Dorsa

In the suburbs, in the eighties, all the girls in my town abided by the same ritual for ear piercing: On a weekend, you begged your parents for a ride to the mall, walked into Claire’s, selected your designated birthstone gem earrings, and squeezed your eyes shut in anticipation of the piercing gun. You sauntered out feeling a bit prettier and definitely socially elevated for a few days, before quickly realizing earrings didn’t really make much difference in the arbitraries of high school hierarchy. So after begging my mother for years to partake in the sacred rite, I recklessly neglected my piercings and let them close. They survived all of two weeks.

One weekend last fall, I was inspired to disrupt my auricular anatomy again, to which my friend responded earnestly, “I think you have to drive to Jersey and go to a mall.” Two young women, a decade or two less ripe than us, tittered nearby and referred us to New York Adorned, where I was promptly informed to make an appointment and return in a week.

I soon learned I was naively trying to book a celebrity piercer by the name of J. Colby Smith, purportedly the most sought-after hole-maker in New York City. (And also Los Angeles, London, and Sydney, as his services are much desired outside the tri-state area.)

Even though I arrived at exactly two-thirty the following Sunday afternoon, it wasn’t until around three o’clock that Smith was ready for me. The 37-year-old looks like rain-battered graffiti sprayed on the side of a Williamsburg warehouse, with faded tattoos embellishing his arms down to his knuckles, across which his lucky number, 108, is tattooed. As a nod to his Salt Lake City snowboarder roots, he wears a knit ski-hat indoors, under which he bares stretched-out, nickel-size holes in his earlobes. His eyes are a washed-out pale blue; he looks used-up and recycled—a guy who earned his scabs and scars.

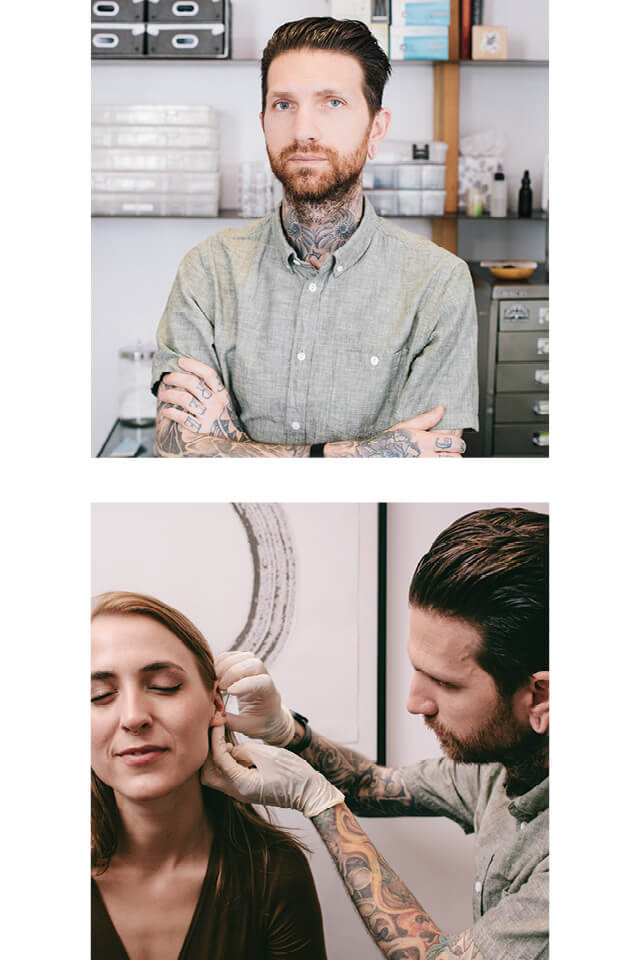

But when he speaks, his voice is an analgesic—plush, melodious, and soothing, like honey chamomile tea. He swiftly examined my ears, focusing on the barely-visible scars in my lobes. “I’m just going to use the old ones. No sense putting holes all over the place,” he stated matter-of-factly. I agreed.

Surgical gloves on, he held a jumbo needle to my ear, and while the words “I’m just going to do it” were still departing his mouth, he had already punctured my right earlobe. I barely felt it. Two minutes later, both lobes were pierced. Immediately after me, two girls shuffled in—one there for moral support. They were high-pitched and nervous. “We’re so grateful for you,” I heard one of them giggle. Smith giggled back. He spent awhile with them.

Smith estimates he sees fifty clients a day. Ten of them are bounce-backs—people who have a complication, or think they do. Two months later, I was one of those ten, concerned that my left ear had gone rogue. He took a brief history from me, examined my ear, and reassured me. He instructed me to clean the piercing with organic castile soap. I was already mentally scribbling down his words as if I were his patient. As a doctor myself, this was an unfamiliar feeling for me.

Curious about the emerging analogues between our jobs, I caught up with him again on his way to LA recently. “I think of it as a game,” Smith told me. I meet clients, and I have twenty minutes to unlock their mystery. Everybody deals with stress in different ways. I need to anticipate what this person needs, put myself in his situation, and figure out what he’s feeling.” He also uses a technique called mirroring to establish rapport with clients. That explained the velocity and direction of our encounters—he had calculated me within seconds of shaking my hand.

Smith grew up as a Jehovah’s Witness but abandoned the faith at twelve years old. Though he habitually ruined family photos with his obnoxious green hair, he still osmosed his father’s life lessons. Smith explained, “My dad always stuck up for the underdog—he treated everyone equally. Being nice to people will get you so much further in life. It’s the way I was raised.” Smith paused to pay the cab driver, apologizing to him for being on his cell phone, then apologized to me for interrupting our conversation.

Smith moved to New York on an impulse, having self-assessed his own outgrowth of his home city. He arrived with six-hundred dollars in his back-pocket after selling his “really shitty car and an even shittier motorcycle.” The cash was gone in three days. “For the first few years, my parents would call me, and I would tell them, ‘New York is so great!’ Meanwhile, I felt so cold and alone.” But to New Yorkers, he evoked comfort and sensibility. He inversely applied his father’s theory of reciprocity to celebrities, treating them like regular folk instead—and they liked it. Editorials and photo shoots came in spits and spurts, then streams and torrents. Smith said, “New York is such an amazing place. I’m living proof of that. I came here with not a clue about what I was doing.” But he still remains tethered to the gravity of his beginnings rather than the levity of stardom.

I told Smith that recently during my ER shifts, I found myself trying to embody his bedside manner. “Wow, that’s the most flattering thing anyone’s ever said to me.” He was silent for a minute, then said, “I grew up kind of rough, I didn’t go to college. But what I learned from meeting so many people gave me an education I don’t think you can ever pay money to get.” ♦

You might also like