Never Say Die: Why Do We Say Passed Away Instead of Die?

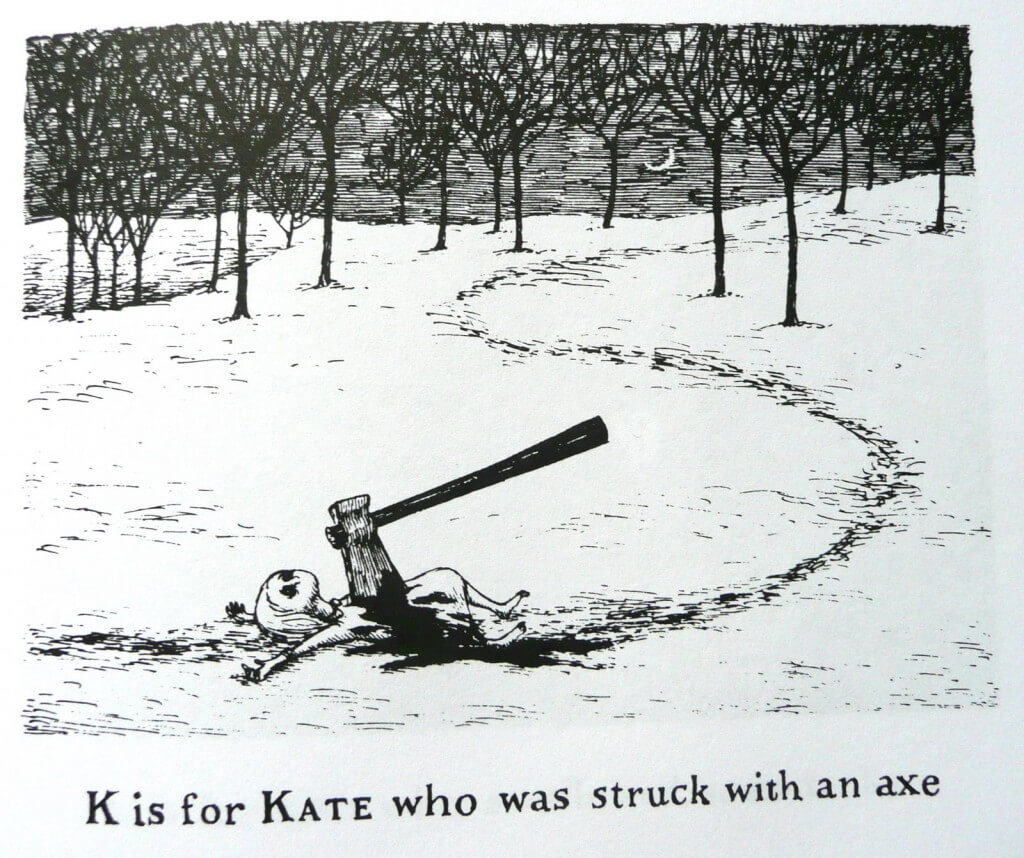

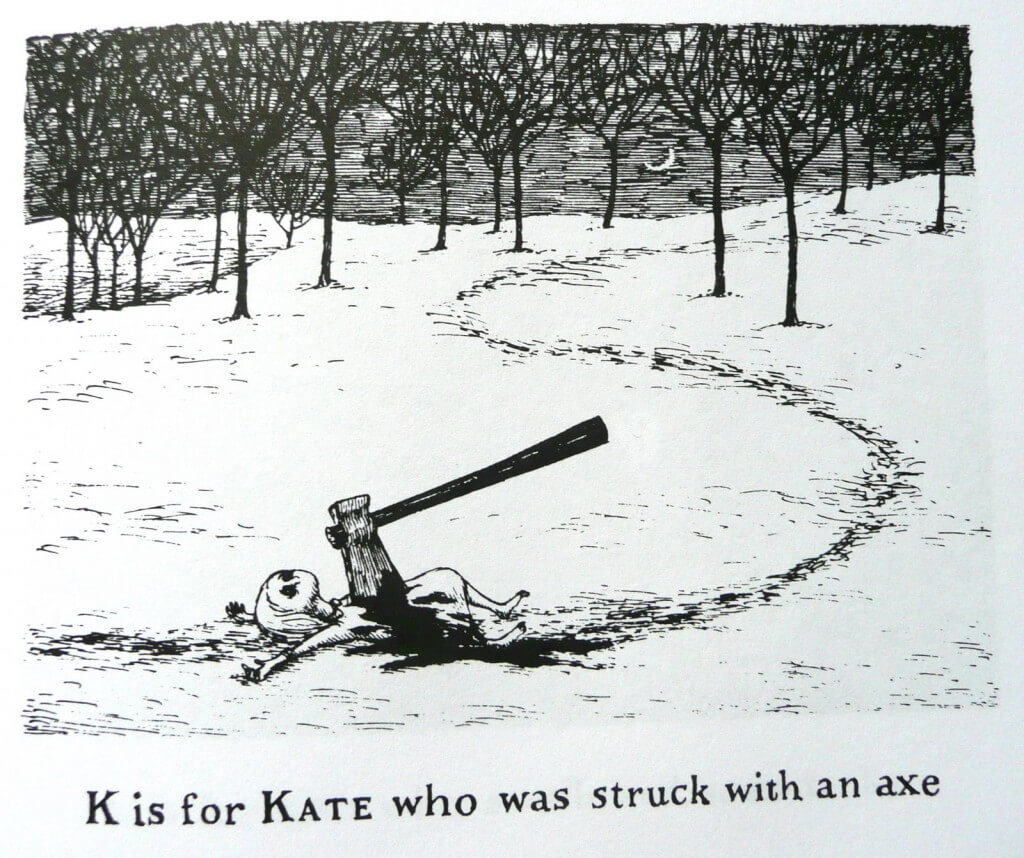

Gory Gorey

There are countless individual quirks in the house style guides of most media companies: Some italicize website names; others only do that for print publications; some believe wholeheartedly in the clarity only an Oxford comma provides; others don’t give a fuck about an Oxford comma. But one thing which I’ve found to be remarkably consistent among well-established media companies is that when it comes to death, there’s no room for euphemism: When someone dies, you say so—not that they’ve “passed away.”

All of which is why I stopped short when I saw the headline on New York‘s Grub Street blog which read: “Josh Ozersky Has Passed Away.” A founding editor of Grub Street, Ozersky was found dead in his Chicago hotel room after a night of attending the James Beard Awards, followed by karaoke. The cause of his death has not yet been determined, but the impact of his life and work has never been more clear, as countless notable chefs and food writers and critics pay their respects to Ozersky’s memory.

And, of course, among those giving tribute is the Grub Street staff, in the form of the previously mentioned blog post, which is a heartfelt paean to the man, and which, notably, employs the euphemism “passed away.” The fact that New York used “passed away” in a headline is a seeming aberration for the publication. Recent blog posts covering the deaths of everyone from Facebook CEO Sheryl Sandberg’s husband, Dave Goldberg, to NYC cop Brian Moore who was fatally shot on the job this past week, to Leonard Nimoy, all use the word “die.” Even when, in the body of an article, a writer winds up resorting to “passed away” (but never “passed,” never that), headlines always remain stark and clear. The word “die” has no ambiguity, and feels almost lacking in emotion; “passed away” has a gentleness that allows us to more easily come to terms with what has happened. The reason the Grub Street headline gave me pause is because it is rare to see that sort of cushioning of the truth in a headline, where economy of words and strength of tenor are highly valued. The reason that Grub Street headline gave me pause is because it betrayed a level of true emotion rarely seen in this context, and made the article’s subsequent tribute to Ozersky all the more powerful.

Anyone who has ever had someone they love die knows how strong the urge is to not believe that what has happened is irreversible. Anyone who has ever had someone they love die knows how easy it is to resort to the kind of magical thinking that allows us to believe that if we just don’t name the terrible thing that has happened, it won’t actually be real. And anyone who has ever had someone they love die knows how hard it is to use the word “die,” a small word that stutters off the tongue and out of the mouth and which, once said, can not be softened or ameliorated. When you’re dead, you’re dead. It’s over. It’s enough. It’s ended. “Passed away” offers the hope of something better, or at least something—somewhere—different. It’s easy to understand why, then, it is so hard to use “die” for someone we know personally, as the Grub Street editors knew Ozersky, and resort to “passed away.” It might be a professional anomaly, but it is eminently understandable on a personal level.

Follow Kristin Iversen on twitter @kmiversen

You might also like