An Octoroon: Reflections on a Play About Race, Performance, and the Performance of Race

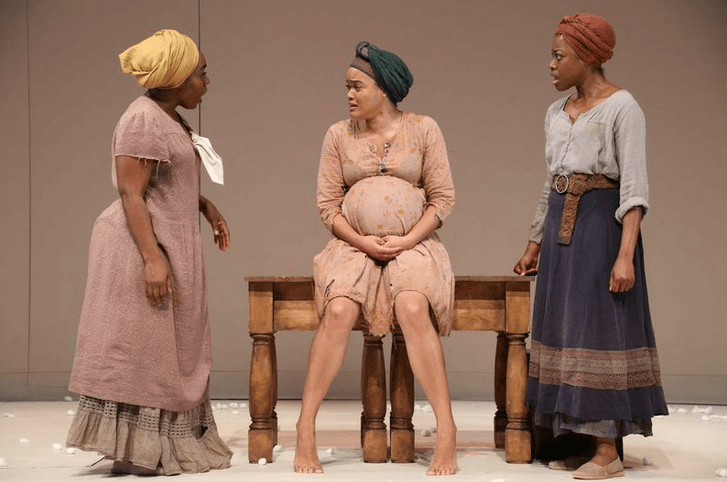

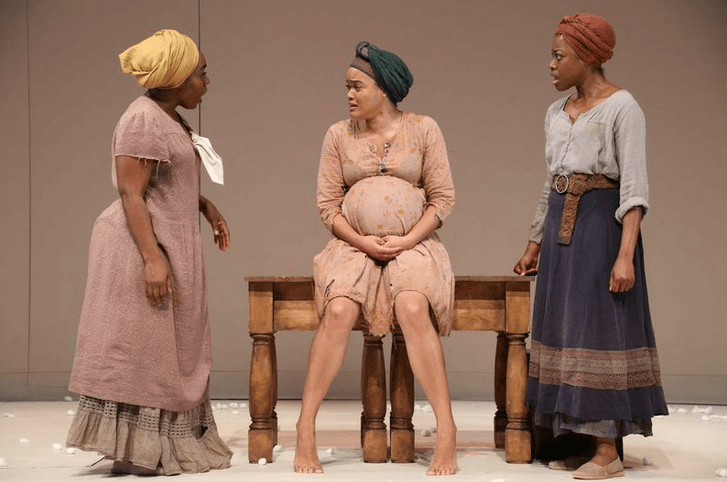

An Octoroon

Photo by Gerry Goldstein

Branden Jacobs-Jenkins knows how to end a play. The last scene of his 2010 play Neighbors (Public Lab) had The Crows, a black family in blackface—Mammy, Zip Coon, Sambo, Topsy and Jim—finally perform “the show” they’d been semi-rehearsing. As it turned out “the show” was the family staring straight at the audience for almost fifteen minutes as “Whistling Dixie” played in the background. When I saw Neighbors, I squirmed under the gaze of the cast and was desperate for an excuse to leave.

In the encore performance of his latest play, An Octoroon (Theatre For A New Audience), Jacobs-Jenkins does something similar—yet this time the gesture is more inclusive and less aggressive. At the end of An Octoroon, the cast sings an original ballad composed by César Alvarez in complete darkness. With the lights out, the audience and cast are united by our inability to look at each other. Jacobs-Jenkins understands that the complicated dialogue between audience and performer has turned into a kind of dual voyeurism, with both parties objectifying the other. But sitting in a pitch-black room, listening to a song that never names the one thing it’s about, I had never felt so responsible as an audience member, nor so painfully aware of my own complicity in a world that fetishized both the performers and the characters they played.

In Neighbors the act of looking, and being looked at, was on the artistic examination table, but with An Octoroon the audience is pushed to do the hard task of self-introspection by having our capacity to gaze taken away. Both moments were highly charged, and it’s out of those uncomfortable spaces that great theatre is made.

An Octoroon is the alternative adaptation of Dion Boucicault’s 1859 melodrama about forbidden love in the Antebellum South. Several years ago I worked as one of two Assistant Directors on Jacobs-Jenkins’s original adaptation of Boucicault’s work at PS122; it was an epic failure. The director, the set designer and half the cast quit right before opening night, and if that wasn’t bad enough, a leaked email from the male lead—about how much he hated the show—was published in the Village Voice. Eventually, all that was left was a play about the difficulties of putting on this play—which, though it wasn’t An Octoroon, turned out to be an intimate and vulnerable production about failure and the nature of collaboration in the theatre. I also like to think that the original experience, no matter how traumatic, gave rise to some of Jacobs-Jenkins’s most delightful and subversive strategies used in the more recent adaptation of An Octoroon.

With no play to put on back then at PS122, Jacobs-Jenkins came out and directly addressed the audience about his theatrical anxieties. In the current An Octoroon there is a similar framework: The character of the playwright (played by Austin Smith) starts us off with a monologue about the tension of being a black playwright. Throughout the production the playwright reappears to take the hands of the audience (or slap them as it sometimes feels) and lead us through the performance. In other words, to borrow from Philip Lopate, Jacobs-Jenkins likes to both show and tell.

Not only did ideas transfer from the first production to this latest, but so did three of the original cast members: Amber Gray (Zoe), Mary Wiseman (Dora), and Gabriel Levy (Ratts/Br’e). Each of these actors has the ability to dip in and out of the over-the-top comedy and melodrama to find at the heart of the text a nuanced pain. And they’re not the only ones—the entire cast (special kudos to Pascale Armand and Maechi Aharanwa, who play Dido and Minnie) gave graceful performances that leapt between a period drama and postmodern hijinks.

There was something special about the first table read of An Octoroon, done in a warehouse so close to the West Side Highway that everyone had to shout to be heard; even in its infancy the play was already crossing boundaries. The success of An Octoroon now is a testament to the importance of both form and theme, and Jacobs-Jenkins’s ability to subvert one, while exploding the other.

You might also like