The Continuing Saga Of The Slave Theater Gets Curiouser and Curiouser

Photos by Nicole Disser

“There are some crazy things about it and some things that aren’t as crazy as people think they are,” Jeff Strabone, chairman of New Brooklyn Theatre company told me over the phone. He was referring of course to the story of the Slave Theater, a place at the center of a real estate dispute full of so many twists, turns, conspiracy theories, and corruption that the word “crazy” doesn’t even begin to capture the situation at all. It’s a real life story that feels more like a dramatization, and the actors involved are as colorful as any cast of characters: real estate developers, the late John L. Phillips (aka the Kung-Fu Judge), so-called squatters, and a new theatre company. While Strabone has an interest in downplaying the drama of the story and focusing on the current and future work of his organization, others like Omar Hardy and his family would rather talk about in starker terms: “It’s a case of good against evil, rich against poor.”

In some ways, Mr. Hardy isn’t far off. However in this case the fight goes well beyond a battle between developers and longtime residents. And the appearance of New Brooklyn Theatre has made things all the more complicated. But let’s go back to the very beginning: The main point of contention here is 1215 Fulton Street, the Bed-Stuy building which long housed the Slave Theater, and its troubled history marked by avarice and deceit. The place is now owned by Fulton Halsey Development Corporation who, according to New Brooklyn Theatre (NBT), have promised at least part of the space to the production company, despite the fact that Omar Hardy (the son of Clarence Hardy, who told the Times is in 2012, “I’m in charge, the only person authorized to be there,”) is claiming his right to the building as well and whose family has been there long before NBT existed.

A walk down Fulton (between the Franklin and Nostrand stops on the C train) will lead to the Slave Theater, which now looks decrepit and imposing— a crumbling dead zone on an otherwise lively section of Fulton lined with hair salons, a residential construction site, a mosque, 99 cent stores, West Indian grocers, cheap clothing stores, and halal buffets. The marquee sags ever so slightly and the sidewalk is uneven and gravely. It may look abandoned on most day but beyond the iron gates, there’s life.

Though you wouldn’t know it based on what New Brooklyn Theatre, a non-profit founded in 2012, says. “One of our main goals was to see if we could bring this building back to life,” Strabone explained. “The building has been closed since 1998. Phillips was named incompetent and had a court appointed guardian who fleeced him and left him powerless to prevent his estate from essentially being robbed. So the building went into disrepair and various people wanted to bring it back, but nobody was able to do that.”

I live just around the block, and the Slave Theater has always struck me as a relic from a bygone era. Though Bed-Stuy remains a solidly African-American community, the Black Power centers seem to be slowly evaporating. See: the closing of True South, an independent bookstore that proudly displayed the visage of Malcolm X in the window, which closed in 2013 and is now a fancy home decor shop.

While speaking with Strabone, I mentioned I live close by to the Slave and still see signage outside calling on passerby to help “Save the Slave,” and once in a while, it’s clear that there’s activity going on inside the building—I’ve seen people organizing, handing out pamphlets, and generally hanging out in front.

“That’s the Hardy family,” Strabone interrupted me. “They’ve been squatters in the building for a long time. They’ve put up their own sign and they’ve broken the law a few times and so on. They claim that they are the true owners and that they’ve been robbed somehow and they’ve got a law suit. We’ve spoken to them a number of times, other local journalists have too, they never specify what court they’re in, whether it’s local or state or who their lawyers are, or who the judge is or what the case is about.”

That’s Strabone’s explanation, but Omar Hardy’s side of the story is completely different. Though he refused to share any documents with me, he was adamant that his family has been in and out of court defending their rights to the property. And a quick look at court records shows that Clarence Hardy pursued two cases against Reverend Samuel Boykin of Ohio, a man who emerged after the death of John Phillips, claiming to be the judge’s nephew and made claim to ownership of 1215 Fulton. (Omar Hardy refutes Boykin’s claim to be Phillips’ nephew, “Boykin is a fraud. Phillips didn’t know him and he didn’t trust him.”) One in 2010 and another in 2012. Both cases have been resolved, but the first was a dramatic one– Hardy requested a restraining order against Boykin, and the judge held Hardy in contempt of court, ordering “Clarence Hardy to vacate the premises known as 1215 Fulton Street,” because of his “blatant violation” of the court’s December 2010 order that he leave the building.

But in 2012 Bank of New York put the building up for auction in light of the multiple liens against the property. Jonathan Solari and Sarah Wolff jumped at the opportunity to purchase the building. They established New Brooklyn Theatre Company and started raising money for a down-payment through a Kickstarter campaign.

“NBT, they come onto the scene,” Hardy laughed, sarcastically. “No problem, cool. They talking about how they’re here to save the day. You come into my community, you don’t talk to me. Logically, if you’re new on the scene and you say you want to save the theater, you should go to the party that’s already there. See whatever the full story is, see how you can assist in helping to save this historic theater.”

According to Hardy, he had to approach NBT himself. “We still rightfully own it, we still possess it, we still go in and out of there every day,” Hardy told me. “Despite these fraudulent developers and all the other opposition, we’re working.”

“Once we launched the [Kickstarter] campaign, the property mysteriously disappeared from the auction calendar,” Strabone recalled. “We contacted Bank of New York [the people holding the auction] and they told us there was a party in contract talks to buy it.”

Apparently Reverend Boykin had somehow pulled the property out of the auction and quickly sold it to a real estate developer, the Fulton Halsey Development Corporation which is operated by Sterling Equities. “Frankly [the bank] wasn’t supposed to reveal this, but they told us who was in contract,” Strabone said.

What happened next is strange, to say the least, and can’t be proven given the lack of a paper trail. “We marched to their office in Bed-Stuy and knocked on the door and said, hey can we talk to you? And that began our ongoing dialogue with them,” Strabone said. “We said, look we don’t think you realize what an historical, cultural asset you have, you can’t just replace it with a pharmacy or a bank. And number two, if you did, there would be a high political cost in this neighborhood that would make other plans of yours possibly difficult because people care about this site.”

Though the real estate blogosphere was up in arms, convinced that the “historic Bed-Stuy theater look[ed] ripe for high-end condos,” Strabone claims New Brooklyn Theatre and the developers came to a verbal agreement.

Surprisingly, Strabone said the developers were “open to what we were saying,” and promised NBT ownership of a theater space, whatever that might look like in the future. But the agreement remains tentative, one based not on a legal contract but in mutual trust. “We hope it works out between them and us,” Strabone said. “We have no reason to doubt their good faith at this point.”

The theater organization says that their goal is to restore the existing theater to its former glory. “Part of New Brooklyn Theatre’s mission is to restore theatre to 1215 Fulton Street,” their website reads alongside a photo of the interior of the building and a recounting of the theater’s storied past. But the Department of Buildings lists more than 20 open violations for the building, and continues to hold a vacate order for the address, one that’s been in effect since 2012 after a floor collapsed. Even Omar Hardy admitted to the presence of serious structural problems.

“The thinking is that the building may have to come down entirely and a new theater built on the space. We’ve prepared architectural specifications,” Strabone said, though he said we’d be “getting ahead of ourselves” in discussing what that might look like. “We’re hoping in the future to build out, and then the theater will be the same size as what’s there now. Again that’s something that’s subject to negotiation, but that’s the likeliest scenario given the structural instability.”

I wondered if New Brooklyn foresees any chance of restoring the existing space. “Ideally we’d rather restore it, but we’re advised that would be a lot more expensive,” Strabone said. “In the end, that’s not a decision that New Brooklyn Theatre will get to make, that’s a decision the owners will get to make.”

This comes as a departure from New Brooklyn’s initial plan. Back in 2012, when the building was still up for auction Sarah Wolff (a theatre producer and one of the founders of New Brooklyn Theatre) told the Daily News, “this building is waiting to be saved.”

Understandably, Hardy finds statements like this to be offensive. “You can’t just come into a community and say… y’all have been here five minutes and you think you know what’s best, while we’re here on the ground fighting tooth and nail trying to save this institution for the community, for Bed-Stuy and beyond.”

At one point during our conversation, Hardy became audibly upset. “I’m sorry,” he said. “It’s just, I’m living it—you know?” But he’s not hating on the newcomers’ mission. “I told [NBT], I like what you guys are doing, but I don’t like how you’re doing it.”

And it’s kind of impossible to hate what NBT’s been doing over the past few years. Despite the trouble with the Slave Theater, NBT has continued to stage productions at other venues in Brooklyn and as far way as Istanbul. They focus on civil rights and activist-style programming, and have revived historically potent plays written by early African-American writers, and they’ve made some remarkable things happen in the neighborhood. Best of all, NBT’s programming has invited in a diverse group of theatre-goers including a good portion of people from the neighborhood.

NBT has garnered a great deal of attention from the Times and for good reason—last year the organization staged a play set inside Interfaith Medical Center in Bed-Stuy, a hospital that was slated to close despite its important role as an employer for a significant portion of the local population.

“I cold-called them,” says Strabone. The next day, New Brooklyn Theatre organizers were meeting with hospital staff and for two months, The Death of Bessie Smith was staged inside the hospital to generate awareness about the closing.

“The reason we did that was to generate attention, publicity back to the hospital—the fact that people would die if the hospital closed. Members of Congress, labor leaders, public health leaders all came and after each performance we had a talk back with the audience,” Strabone explained. After the play closed, the state decided it would keep the hospital open. “It was an activist-theatre dream come true in that doing the play actually led to that outcome,” he said. “That hospital is still open.”

NBT has a full season of programming scheduled for the summer including plans to produce Rachel, a play written in 1916 by Angelina Weld Grimké, the first play by an African-American woman to be staged.

But regardless of the positive things New Brooklyn Theatre has done (and not just for theatre, but for the community), Hardy is dubious about the relationship between New Brooklyn and the mysterious “millionaire developers” as he called them. “I look at it as a strategic maneuver by the opposition,” he said. And there’s no doubt New Brooklyn Theatre is definitely the newcomer here and their language rings more than a little of paternalism. Their name pretty much says it all.

Though it should be noted Jeff Strabone has a history of going up against developers. In 2009 when Strabone was serving as president of the Cobble Hill Association, he rallied against Two Trees (the same developers behind the Domino Sugar Factory site) when they broke with Cobble Hill Historic District rules restricting the height of buildings so they could construct penthouses atop an Atlantic Avenue development.

But Hardy pointed to the lack of a contract or formal agreement between the Fulton Halsey developers and New Brooklyn as evidence that something suspicious is going on. “Of course they don’t have a written agreement or anything,” Hardy said. “They shook hands or something, some mumbo jumbo, but [NBT] is saying they are definitely going to operate the downstairs. Whatever the case may be, they’re dealing with [the developers] Fulton Halsey—and they made an illegal transaction.”

The Hardy family claims the sale of the building was illegal because it didn’t legally belong to the estate of Judge Phillips when Boykin sold it. “My father and Mr. Phillips they were good friends, they were business partners, and Judge Phillips was basically my father’s mentor,” Hardy explained. Clarence told the Times back in 2012, “This was Mr. Phillips’s vision, and I’m going to do all I can to keep it going.” Though how the Hardys came to own the building exactly is a matter of dispute, and one buried under piles of false documents and corrupt schemes orchestrated by local attorneys, allegedly including former Brooklyn DA Charles Hynes.

The story of the decline of the late Judge John L. Phillips is where the real “evil” Hardy referred to can be found and what holds the key to the multi-million dollar question of who actually owns the Slave Theater.

In 1984, the eccentric Judge John Phillips bought the building, formerly known as the Regent Theater, with the intention of rebranding it as a center for black political activity as well as a community arts space, thus renaming it the Slave Theater. Phillips had his hand in a lot of activities, perhaps most famously martial arts (he was known as the Kung-Fu judge for having founded the Gorilla Gnat System of Scientific Movements and Defensive Fighting) but for a time he dabbled in filmmaking too. In the early 80s he made a self-financed romance film and after encountering difficulty finding a distributor, he bought the Regent so he could have a venue of his own to screen the film. The Slave became a center for Civil Rights activism in the community; Reverend Al Sharpton held weekly meetings there in the late 80s.

According to the aforementioned 2012 Times article, as the owner of a number of Brooklyn properties, the Judge was a very generous landlord. It’s known for sure that he was eventually the victim of property theft, but when that all began is a matter of dispute.

Strabone suggested how I might go about finding public documents, something I’ve done once or twice. He encouraged me to go digging. “There’s no mention of the Hardys on any of the deeds going back to 1967,” Strabone claimed. “So I think they have a different model of ownership than most people, to put it diplomatically.”

But according to property records, the deed changed hands multiple times between 1985 (when it was transferred to 140 Herkimer Street Realty Corporation, though signing off a property to either an LLC or corporation is a common thing to do for property owners, if not something that makes for opacity or “well cloaked shell ownership”) and now.

Omar Hardy was insistent that his family has owned and operated the building since 1999. “Mr. Phillips didn’t own the theater, he was a lawyer for our corporation,” Hardy explained. And, in fact, a 1999 deed indicates 155 Herkimer Street Realty Corporation (which had claim to the property’s deed since 1991, according to documents) signed a co-ownership deed with J.J. Real Estate Corporation, what Hardy claims is his family’s company.

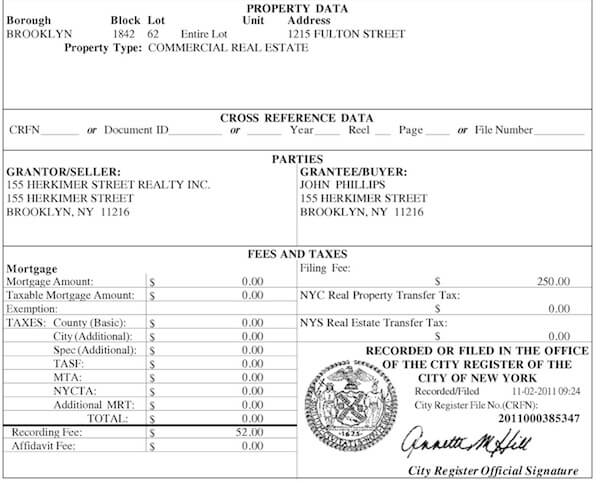

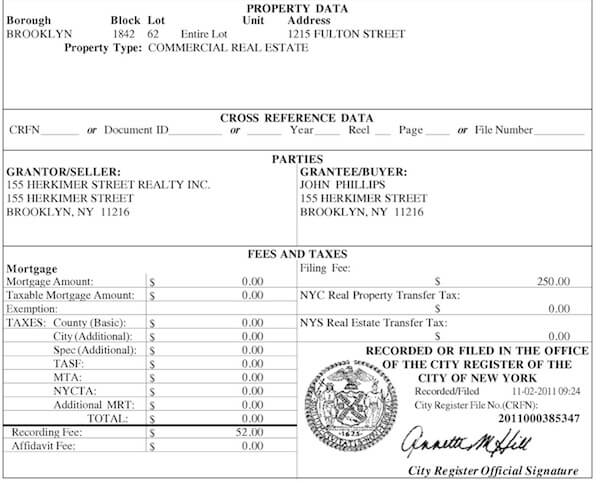

Besides multiple tax liens taken out against the building, the deed doesn’t budge again until 2011, when part-owner 155 Herkimer Street Corporation transfers ownership to “John Phillips” of 155 Herkimer Street; Judge John Phillips had already passed away, broke and confined to a nursing home (A judge decided in February of this year that the Prospect Park Residence was responsible for the wrongful death of Phillips, who reportedly froze to death after the heat had been shut off in his room for two weeks). It’s more than a little strange to see a dead man’s name as the “buyer” on a deed.

a portion of the 2011 deed (ACRIS)

“Everything [Samuel] Boykin’s been doing is wrong,” Hardy told me. “Not only wrong but illegal. In 2012 he tried to sell some properties that were not in the estate of Judge Phillips. But through fraud and trickery, he made it happen.”

On sight the 2011 deed simply doesn’t add up. And judging by how many attorneys were involved in blood letting Phillips’ estate, turning up fake records isn’t out of the question.

Things had started to go downhill for the Judge in 2001 when he made clear his plans to run against existing District Attorney Charles Hynes. It was later discovered Hynes abused his power to target political rivals, including orchestrating “politically motivated prosecutions,” like allegedly convincing a colleague, Attorney Frank Livoti of Long Island, to pursue charges against Judge John Phillips. Under New York State law, almost anyone (besides family members and heirs, “a person otherwise concerned with the welfare of the person alleged to be incapacitated”) can bring a case against someone alleging they are mentally incapacitated. Livoti won the case in 2003 and perhaps more disturbing, he became the legal guarding of Phillips, a man he didn’t know at all.

Phillips’ guardianship passed through multiple hands before prosecutors finally discovered something was amiss. Emani Taylor, a Brooklyn-based attorney was found to have been “improperly enriching herself from the Phillips estate,” raking in more than $300,000. Taylor was one of many who stole from Phillips while he was still alive; she was eventually disbarred.

And though much of this information was uncovered by journalists back in 2007, as the Brooklyn Rail predicted, the story of John Phillips has almost effectively been “erased.” NBT acknowledges the judge was a victim, but they do not agree with claims that the sale of the Slave Theater was illegal.

I tried contacting the developers, who Strabone warned me “don’t talk to the press,” and have received no response.

“If you guys want this property or you legally own it, then why haven’t I been arrested or anything?” Hardy argued. “Because they are frauds, they think we are just going to walk away, they think we’re just going to give up.”

But Hardy remains steadfast and is confident the developers are in a weaker position. “This Slave Theater thing is a big deal, it’s an institution that needs to be utilized by the community, especially with all this madness that’s going on. Our boots still have to be on the ground, we still have to maintain our property, and stop these guys from doing what they’re trying to do.”

You might also like