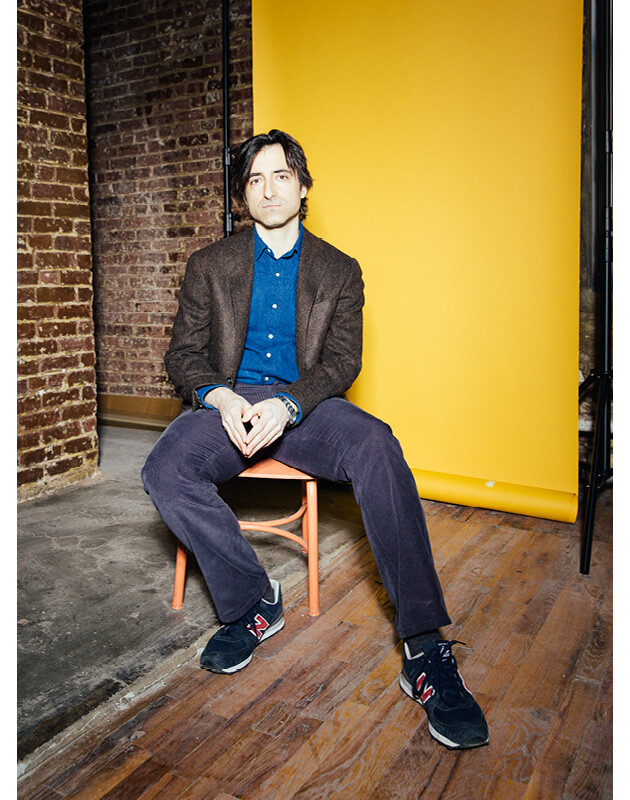

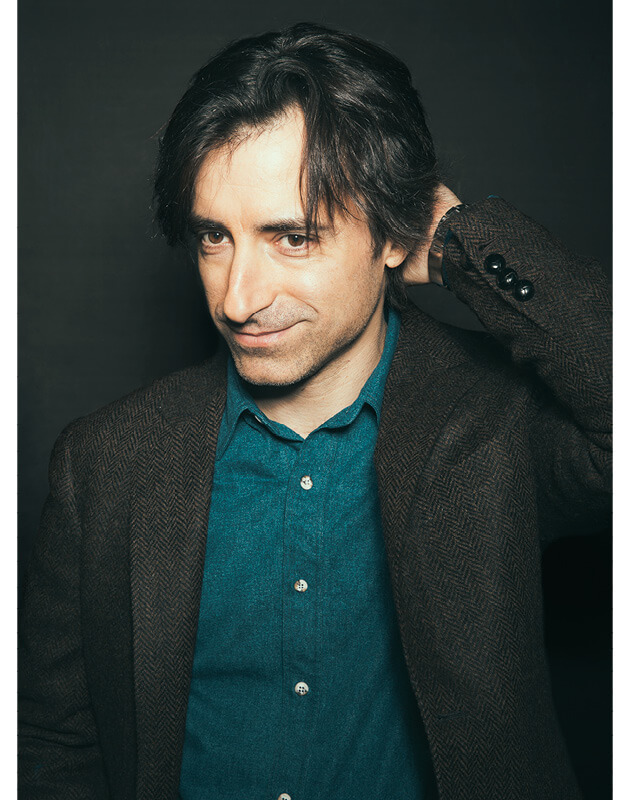

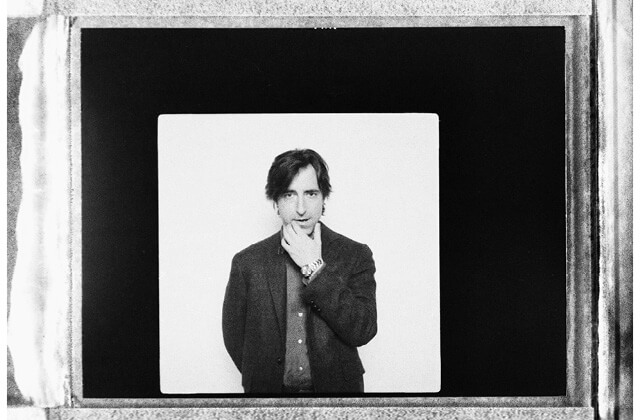

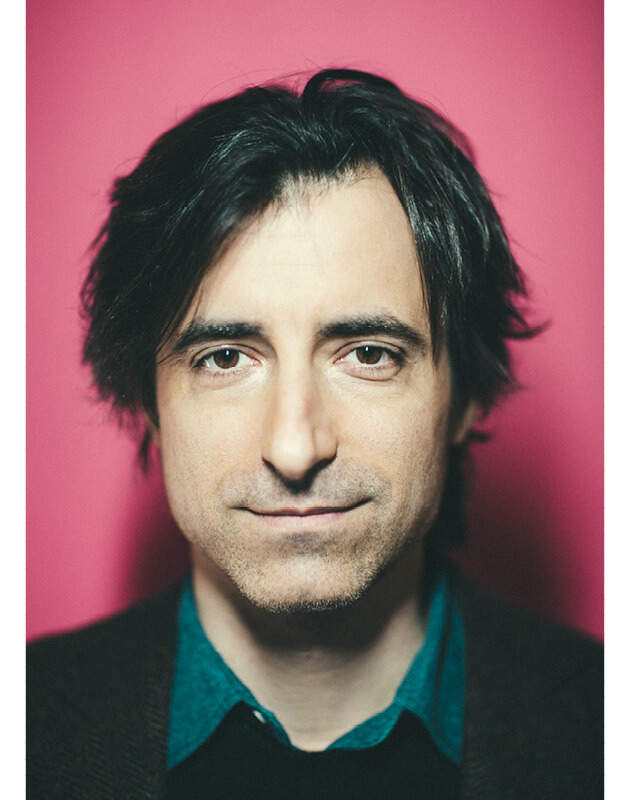

Noah Baumbach on Creativity, the Perils of Aging, and… Hipsters?

All photos by Eric Ryan Anderson

The first thing you notice about Noah Baumbach, the writer and director of films like Margot at the Wedding and Frances Ha, is that he is exceptionally well put together. Handsome, even. I am meeting Baumbach at Casa Mono, the Michelin-starred, Mario Batali-and Joseph Bastianich-owned tapas restaurant around the corner from his Gramercy apartment. It’s a blustery, freezing Friday, the coldest day in New York City this year, and OK sure—Baumbach’s just come from a photo shoot. Of course he looks composed. But one gets the impression that here’s a man who cares about details.

Baumbach built his reputation on a string of films, beginning with the 2005 breakthrough The Squid and the Whale, that unsparingly zero in on some of life’s more unseemly details—divorce, disappointment, death. His films are often about characters who are forcibly removed from their context, or whose context is changing faster than they can control, and the behavioral folly that results from such upheaval. As the titular character in Baumbach’s 2010 film Greenberg says, “A shrink said to me once that I have trouble living in the present, so I linger on the past because I felt like I never really lived it in the first place, you know?” The prototypical Baumbach protagonist is like that: bilious, acerbic, a bit misanthropic, “kinda angry at the world and not sure why,” as the director himself puts it. “Especially with those two movies after Squid [2007’s Margot at the Wedding and Greenberg], I was pressing down on things that I found true, but were also potentially pricklier aspects of human behavior.”

So when Baumbach released Frances Ha, in 2012, critics and audiences alike were surprised. The film is a black-and-white comedy about youth in New York (which earned it a fair few Manhattan comparisons) that Baumbach co-wrote with Greta Gerwig, who also stars in the film. (The two became a couple during filming.) Frances is a 27-year-old wannabe dancer marooned in the gulf between her ambition and reality. She dreams of the bright lights and a fulfilling relationship, but her moves are coltish, she’s broke, and it’s her best friend who’s the one getting married and moving into her dream apartment. Frances fits the Baumbach mold—she sees herself one way and the world sees her another—but the film is marked by a sensitivity, generousness, and joy that felt like a breath of fresh air compared to the oppressive dourness of Greenberg and Margot at the Wedding. It was as if by removing the color from his film, Baumbach had let in a little light.

Now, this month, comes While We’re Young, a goofy, glossy comedy that deals with another common Baumbachian concern: aging. Ben Stiller plays Josh, a neurotic fortysomething documentary filmmaker who’s having trouble finishing an epic political film that his father-in-law, a celebrated director, describes as a “six-and-a-half hour film that’s seven hours too long.” He and his wife, Cornelia (played with brio by Naomi Watts, who does a lot with little), watch as their friends acquiesce to middle-age: They’re having kids, or going home early, if they go out at all. Meanwhile, Josh and Cornelia are childless, frustrated or betwixt and between, ensconced in a life dulled by routine. Their lives are comfortable but rudderless—outwardly appealing, but inwardly vacuous.

That is, until they meet Jamie (Adam Driver) and Darby (Amanda Seyfried), a twentysomething bohemian couple living in Bushwick whose exuberance and creativity Josh and Cornelia easily fall in love with. (It helps that Jamie fawningly enthuses over Josh’s work—misery loves flattery.) Jamie and Darby are near-parodic sketches of Brooklyn hipsters: They hoard vinyl, ride bikes, use a typewriter, explore hidden train tracks and abandoned water towers, fetishize their parents’ pop culture, eschew Facebook, etc. Some of the satire feels sharp, and some of it feels sloppy and outdated. “You’re dealing with the clichés of Brooklyn, which in some sense I chose to ignore and not worry about,” Baumbach explains. “There was a certain point where I was like, ‘I don’t know if anyone’s roller blading anymore, but I’m sure they will be at some point, probably by the time the movie comes out.’”

Jamie and Darby inspire Josh and Cornelia to relocate their own joie de vivre, and the generational gap is fertile material for broadly humorous gags, such as when Darby takes Cornelia to a hip-hop dance class, or the couples go to an ayahuasca retreat. Hijinks ensue. It’s also a battleground for warring artistic egos—suffice to say, there’s more to Jamie than first meets the eye (the same can’t be said for Darby, who, like Cornelia, is sadly underwritten).

“There’s a line I had to walk to convince the audience that Josh and Cornelia are going to fall for these people, without selling them out,” Baumbach says. “But I also wanted it to be funny, and for that it has to be somewhat ridiculous. It’s an essentially funny idea, falling in love with a young couple.”

While We’re Young is Baumbach’s most accessible film. And it’s not just the cast—the setup and the humor are as close to mainstream as the director has gone, thus far in his career. “I was thinking of movies the studios used to make when I was a teenager in the 80s,” Baumbach says. “Movies that Mike Nichols or Jim Brooks or Sydney Pollack would direct—every year, there was a smart comedy about adults. There was something kind of fancy and nice about them.”

Fancy. Nice. Comedy. Could it be that Noah Baumbach is…happier?

When I suggest this, he chuckles, his wary, taciturn face crinkling into a smile. “The story just naturally felt this way,” he reasons. In Frances Ha, While We’re Young, and Mistress America, another upcoming feature co-written by and starring Gerwig, Baumbach says he “wanted to tell stories that were no less true, but are just different angles on human behavior. If you look at filmmakers I really admire who’ve had long careers—Rohmer, Truffaut, Bergman, Woody Allen—they did different takes on similar themes. Some are sunnier, some are darker, but for those filmmakers, their genre is their personal movies—a Bergman movie is a Bergman movie, even though the films are pretty varied.”

Baumbach sees himself in this vein—if not necessarily the equal of those luminaries, then operating within the same tradition. “For whatever reason, I always felt that movies could be a way to express personal views and experience,” he tells me. Baumbach is often asked if his films are autobiographical, and indeed his work often seems to interrogate aspects of his own life—his postgrad years, in Kicking and Screaming, or his parents’ divorce, in The Squid and the Whale, or the anxiety of turning 40, in Greenberg. But those are “often not actual experiences I’ve had,” he points out. “They’re interpretations of characters or experiences. By the time I’m done writing a script, and certainly by the time I’m done shooting a movie, it’s been twisted and turned in so many ways that it has little actual bearing to anything that went into it.”

Baumbach, who’s 45, was born in Brooklyn to the critics Jonathan Baumbach and Georgia Brown, and grew up in the Park Slope of the 70s and 80s. From an early age, he knew he wanted to make movies, but had no idea how one actually did that. “It was just a kind of idea,” he says. “I don’t think it felt like something that would ever happen until it did.”

But he always thought in terms of movies, writing stories and sketching out ideas that he could imagine on the silver screen. As a boy, Baumbach’s parents frequently took him to movies at the Plaza Cinema on Flatbush, which is now an American Apparel. His father, in particular, would often take him to films “that I wasn’t quite ready for”—R-rated fare like The Jerk, Animal House, and Apocalypse Now (an “oh shit” moment, Baumbach says). “These things were mysterious—they would just arrive, fully formed. I never knew what was coming. It seemed so magical to me.” Baumbach would see all the films made by the Saturday Night Live stars of that era—Steve Martin, John Belushi, Bill Murray—and comedy has always been important to him. He is perhaps more apt than others to think of all his films as comedies.

Like many other cinephiles, Baumbach’s cinematic education broadened and deepened in college. He got “very into” the American independent auteurs of the late 80s, including Jim Jarmusch, Spike Lee, and the Coen brothers, as well the European canon. He took a screwball comedies course and became enamored with the works of Howard Hawks, Preston Sturges, Ernst Lubitsch, and Frank Capra. And he was obsessed with Woody Allen. By 27, Baumbach had made Kicking and Screaming and Mr. Jealousy, two glib comedies of manners about urbane young men in ill-fitting sports jackets that bear some resemblance to the work of Allen or Whit Stillman.

Those directors, the cinematic poets of New York in the 70s and 80s, stoked in Baumbach a smoldering fascination with the city as a template for expression. Growing up, he “fantasized about living and working” in Manhattan. He laughs. “The joke on me is that everybody moved to Brooklyn. But for all the issues I have with how Manhattan has changed, I still do love living here. I love the street culture, the energy, taking my son to see the knight armor at the Met, being around it all but able to stay in your own space at the same time.”

Baumbach is a creature of habit, returning again and again to the same restaurants and cafes as he does themes and character tropes. He often likes shooting in familiar places that carry prior associations. Even Greenberg, which was shot in Los Angeles, was largely filmed in neighborhoods and restaurants Baumbach knew from his brief attempt to live there. “There’s real merit in going to a new place and seeing it for the first time,” he says, “but shooting in New York City gives me ideas. I don’t know the brain science, but it triggers some part of my brain that seems to feel creative.” Even Casa Mono, the setting of our interview, is a familiar locale—soon after Baumbach sits down across from me, a waiter poured us two flutes of the house cava. They were gratis, a privilege reserved for regulars. “He’s been so good to us over the years,” a hostess told me afterward.

With While We’re Young, Baumbach wanted to “embrace the city both as I love and remember it, and also as it is now in ways I don’t know as well—Bushwick life.” He’d also, for many years, wanted to make a comedy about couples that explored the individual dynamics within a larger group dynamic. He played around with several ideas, but nothing came together until he started thinking about middle-age. “You know, that feeling you realize every adult feels, once you get there, of still feeling younger than your actual age,” he says. “Of just starting to figure things out, and then realizing you’re not young anymore.”

Baumbach can relate. “I was 24 when I made my first movie, and I was so used to being the youngest person in the room. People were always asking, ‘How old are you?’ That seemed to go on for quite some time. Then, all of a sudden, no one’s asking you that anymore.”

That’s why Josh, Ben Stiller’s cranky character, clings to his artistic purity like a life raft—if he’s not going to be as successful as he’d hoped, well, at least he won’t indiscriminately appropriate, like the younger, up-and-coming Jamie. “It’s folly,” Baumbach explains. “Josh invests Jamie with so much more power and significance than any people should have, certainly than any twentysomething Bushwick people should have.” Josh’s investment in Jamie is more about his own desperation, his growing sense of obsolescence. It’s inevitable that it wouldn’t end well. Baumbach compares the power dynamics between the two main characters to the fable of the Scorpion and the Frog, in which a scorpion asks a frog to ferry it across a river. The frog, fearful of being stung, is reluctant, but the scorpion argues that stinging the frog would sink them both. The frog agrees, and begins swimming across the river with the scorpion on board. Halfway across, the scorpion does indeed sting the frog. Before drowning, the frog asks the scorpion why it stung him after all, to which the scorpion replies: “It’s in my nature.”

Baumbach doesn’t see much of himself in Josh, though. “It’s not an accident I’m making movies professionally,” he says. “I tried really hard to do this, and Jamie understands that in a way Josh is embarrassed by.”

Still, the tightly-wound, angst-ridden Josh is perhaps less Baumbach’s opposite, and more his dark shadow. After all, he sweats the small stuff. He’s at the very beginning of working on something new, which he won’t tell me much about. He’s in that place where “you forget all the hard parts, and that you had this exact feeling on the last one. You’re just back to hating what you’re doing and struggling with it. Then you get through it. And once the films are done, they’re these imperfect things you hoped would be perfect, and they’re out in the world. Now I’ve got a few of them, so people can tell you which is their favorite.” •

Hair and makeup by Joanna Pensinger.

You might also like