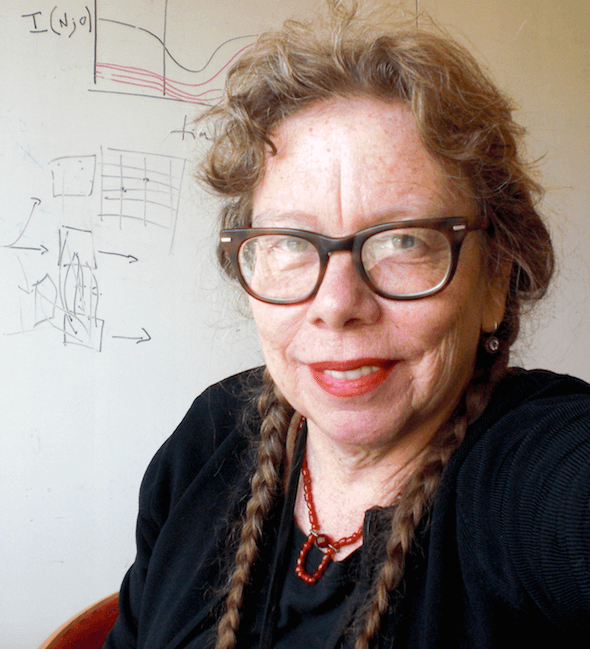

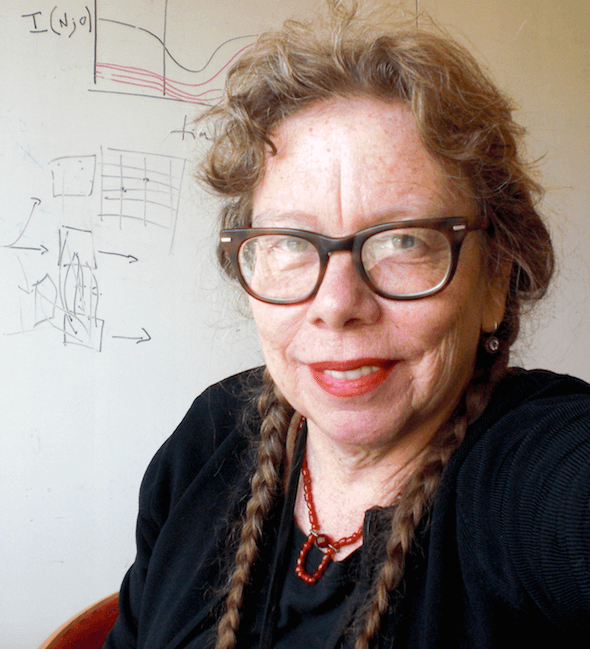

Talking with Lynda Barry About Cartooning and the Counterculture

Lynda Barry

Tonight at BAM, Lynda Barry and Matt Groening—highly acclaimed cartoonists, yes, but also former college classmates—will appear in conversation, talking “about 40 years of love, hate, and comics and the perpetual joy of driving each other crazy.” Groening is, of course, the legendary creator of The Simpsons, and Barry is a similarly celebrated cartoonist and teacher, whose latest book Syllabus: Notes from an Accidental Professor is a vibrantly rendered look at the relationship between the mind and hand and the resultant images. Recently, I spoke with Barry about her work at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, her decades long friendship with Groening, and what she sees as the role of a cartoonist in the world today.

Hello! So before saying anything else, I wanted to tell you that I’ve been checking out your Tumblr, the one you use with your students, and I just love it. Did you start using Tumblr when you became a professor? Or was it something you’d already been doing?

Well, actually, I started putting some stuff up right before I started teaching. But when I started teaching, I thought it would be something for just my students. But actually at this point we’re just 13 shy of 97,000 people! [Ed. note: It’s no doubt surpassed 97,000 by now.] There are a lot of people who follow it, which makes me wonder what they get out of the extra credit ideas! It’s really fun to use, even if it’s hard to search through; you have to just go through the archives, which is also kind of fun.

Yeah, I feel like Tumblr lends itself to discovery in a way that seems very much like how the Internet was originally sold to me when I was a teenager, as something you could just endlessly search through.

I agree with that! And the other thing about Tumblr is that it helps you with the desire to share the things you find.

Plus, for you, it must be a great way to share with your students, who probably already use it. And I commend you for that, because it’s nice to have a professor who’s that in tune with the ways students consume information these days.

It’s been really great. I love my students so much. It’s a neat way to present and still be part of the class. The thing that I always tell my students is that the hardest thing is being able to give their work back to them because they’re never going to love it as much as I do.

So your latest book’s title references the fact that you’re an “accidental professor.” What was the path to being the accidental professor? Is this a career that you always sought in some way?

I’ve always been interested in how images move between people. And also what images are; this is a question my teacher asked me when I was nineteen. And I realized that about five years ago, I’d been teaching workshops for a while, and I’d learned so much from teaching because you really learn about your field of study. I’d gotten as far as I could with my own practice teaching these workshops when I saw there was an artist-in-residence position at the UW, about an hour away from where I live. And I looked at it and I thought, well, I will get a class for a semester and find out more of how images move. The other thing I was interested in was witnessing what it was like when you walk someone who has given up on the possibility of drawing, what happens when you walk them back, not for the purpose of making something that’s pleasing visually but more as something that would bring them back to a completely different arena for thinking.

And then I got the position and I just fell in love with it. There’s something about walking into a room where you have twenty really smart brains and bodies. And I really stressed having an interdisciplinary class and the widest age range I could manage. After that first semester I was just hooked. And the university has just allowed me to do really peculiar things. One thing I’m doing right now is working with a lot of grad students, particularly PhD students, and I’m pairing them up with and getting them to work with 3- and 4-year-olds. So basically what they’re doing is I’m having them go into these different Pre-K schools and having them be a Pre-K kid again. So they have to participate in circle time and sit on the ground, but mainly I want them to see what human beings are like before everything is categorized. Because that state of mind is very much the state of mind that I’m encouraging everyone to get to before they draw. It’s a completely different way of thinking of things. It’s the difference between creative reasoning and argumentative reasoning. And argumentative reasoning is what’s foisted on PhD students.

It’s hard to be present and creative when you’re constantly trying to figure things out or put labels on them or intellectualize every little last thing.

I have a little lab at the university now and I get people to come in the lab and work. And one of the things that everyone says—and I think it has to do with the shift of mind that takes place there—they always talk about how long it’s been since they’ve done something like that, and there’s always some sadness. And they talk about how their sense of time gets warped. And the last thing they say is how they feel refreshed physically after working with children; those three things are something that’s worth researching, I think.

I feel so lucky to be teaching now. In one way it was an accident, but I really owe a lot to my teacher at the Evergreen State College, which is one thing Matt [Groening] and I are going to talk about.

So you and Matt have known each other since college?

We met when he was the editor of the school paper. This was a little experimental college back then, it wasn’t even accredited the first year I was there. I was from Washington State, and Matt came up from Portland. When he became editor, he made this announcement at the paper that he would print pretty much anything anyone submitted, and I remember reading that and thinking “Realllly?” And so I tried to write things that he wouldn’t print. So the first thing I wrote was an outraged letter to the editor about soemthing that had happened to me in the Girl Scouts in the fifth grade. And he printed it. I kept trying to find crazier and crazier stuff. And I started doing comics, these little cartoons, and the first one I submitted was an argument between two guys, and one looked like a regular guy and the other one had no legs and was on a skateboard. And the two of them were having an argument about which it was worse to be: and asshole or to have no legs. And in fact it’s not a very good comic at all! It’s very offensive, but he printed it! The other thing about Matt was that this was a hippie college. It was a hippie college in 1974. But Matt wore Oxford shirts and khaki pants and shoes with laces. I had no idea at the time, but that outfit was calculated to annoy the hippies. Our friendship began as a way to irritate others, or to challenge others, and it’s been that way since.

I can’t think a more beautiful beginning to a friendship! Sounds like he was the perfect counter to the counterculture.

Isn’t that him? Isn’t that him all over? He always loved butting heads with tyrants. He is the only guy I know who gets giddy over getting a phone solicitor. Mostly because he likes to lead those guys on. Like someone will try to sell him a condo in Florida, and he’ll talk and talk and then suddenly ask: “Does this come with noodles? Hot buttery noodles?” And that will drive them crazy and that makes him the happiest. Matt takes great delight in that kind of stuff.

It all comes back to the whole idea of challenging authority…

I think it’s certainty that he challenges.

Which makes me think of how cartoonists actually fulfill that role in such a specific way. What about the medium of cartooning makes that possible?

I think one thing about comics is that I think they’re very fast. I was talking with Art Spiegelman about the nature of comics, and one of the things I said that’s really wild about comics is I can sit down with one scrap of paper and a pen and I can draw a comic and hold it up to you and it will make you want to punch me in the face! There’s nothing else like that. And Art pointed out that there’s also intent in it. That’s something I necessarily wouldn’t have put in there, but it’s true. It’s just paper with ink on it but it will make people react. It does that faster than just thinking.

Right, and with speech, the words vanish when they leave your mouth, but an image is indelible.

I think so too. I think people feel like they have a voice in cartoons. Chris Ware has an amazing saying about how people go to a museum and if they don’t get a piece of art, they think they’re stupid, but if they’re looking at a cartoon and don’t get it they think you’re stupid. And I love that! It makes everyone feel like they can access the ideas behind it. Now it’s getting a little beyond that because it’s a field of academic study, but I feel like comics are sort of every man’s way of looking at a story.

This interview has been edited and condensed for publication.

Follow Kristin Iversen on twitter @kmiversen

You might also like