New York City One Step Closer to “Banning the Box”

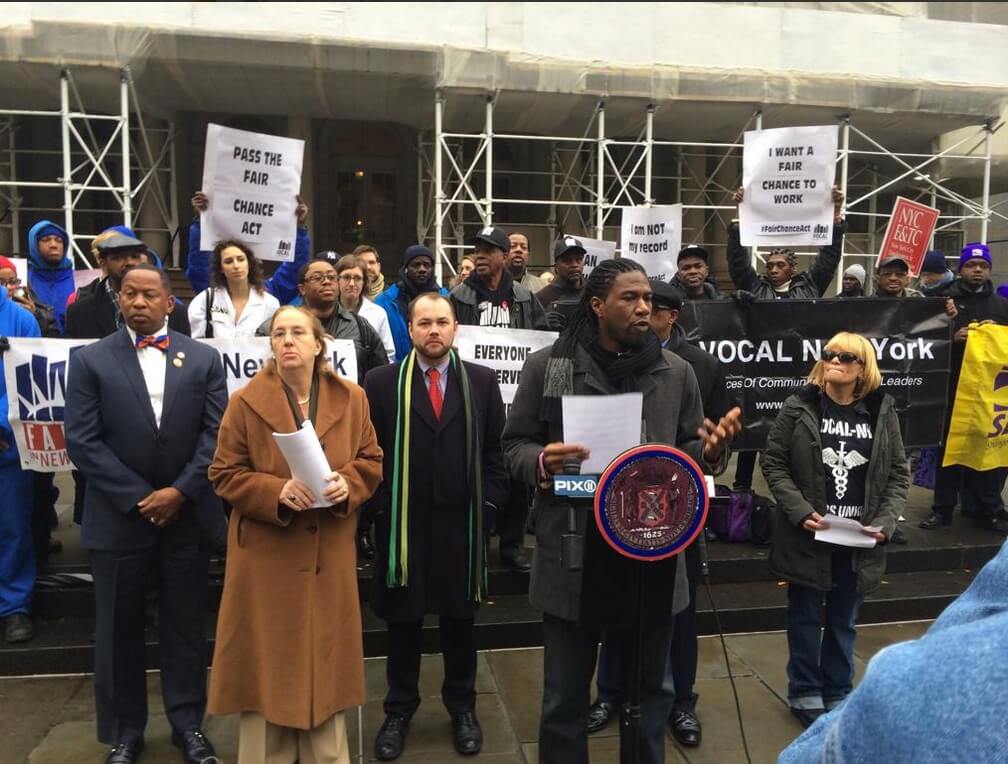

City Councilman Jumaane Williams speaks outside of Fair Chance Act hearing (Photo: Jumaane Williams Twitter)

Last Wednesday, city council members reviewed a bill for something called the Fair Chance Act, which would prohibit employers from inquiring about criminal history during the job application process. If it passes, job applicants across the city would not longer be prompted to check a box if they’ve been convicted of a crime.

In the state of New York, it’s already illegal to refuse someone employment based on previous criminal convictions, unless the crimes committed are directly related to the type of work that person would be doing. Yet employers are still able to get away with this type of discrimination because it’s hard to prove their intentions.

We spoke with the Alyssa Aguilera, political director of Vocal New York, an interest group that played a central role in calling on the city to reform stop-and-frisk and change policies toward marijuana. The organization started out as an AIDS advocacy effort in the early 90s, but has since expanded their policy.

Vocal NY has formed a coalition, Fair Chance NYC, in support of this particular legislation. “We have 35 supporters–” out of 51 city council representatives–”which means we have a veto-proof super majority.” So unless something goes very, very wrong, the bill is pretty much in the bag—it’s just a matter of when exactly the measure will pass. “We’re trying to get it passed by the end of the years,” Aguilera explained, though admitted it might drag on until early next year.

At last week’s hearing, the council heard testimony from advocates, personal accounts from formerly incarcerated people and others who have been convicted of crimes in the past and experienced the effects of the “box.” “They are still having to check the box, when it’s really not who they are anymore. It’s something they’ve worked hard to move past,” Aguilera said.

There were also a few others who testified against the measure. According to Aguilera, their views demonstrated that the box continues to exist because of a “fear-based stigma that says we can’t trust these people and we’re unsure of their ability to be good employees,” she said. “I think their concerns and their fears really exemplify why this legislation is needed.”

The proposed legislation would not stand in the way of employers ever knowing about an applicant’s criminal history, however business owners wouldn’t be able to access a background check until after making a job offer. By isolating this variable, it would simply make it more difficult to discriminate against eligible employees. Aguilera argued this would also help protect business owners. “It will be helpful to break down the biases of employers,” she said.

According to the National Employment Law Project, though most states have either banned the box or entirely or have at least one county or municipality with a similar law on the books, New York City lags behind. But Aguilera understands this as an advantage. “This will be the best Fair Chance policy in my opinion,” she said. “We really did our best to comb through all the different ordinances and pick the elements of it we think are the strongest and will do the most good and cobbled them together.”

While some big corporations like Bed Bath & Beyond, a business that was targeted by the attorney general after announcing at a job fair that felons need not apply, have voluntarily eliminated the box from their applications throughout the country, many companies still pose the question of past criminal convictions to applicants.

But Aguilera thinks that a push in New York City will set the standard. “It’s so important because there are so many major organization and retailers in New York, and we can say hey, if you’re living up to these standards in New York City, why can’t you elevate the standards elsewhere?” she said. “We’re hoping it will be a model policy that will be exported to the rest of the country.”

You might also like