DEBUT: Emily Terndrup and Derrick Belcham at the Knockdown Center

There is no good way to get to Maspeth, no matter what the neo-natives tell you. There are only worse or better ways, weighed among the pilgrims. “By bike” is the quick answer, but there is no guarantee you or your vehicle will arrive in one piece, if at all.

Last night, I was on my way to Maspeth to see the final, sold-out performance of Debut, a new show put on by Emily Terndrup and Derrick Belcham at the Knockdown Center in Maspeth, Queens. Like most things on Flushing Avenue east of the L, the Knockdown Center looks like a garage or an auto body shop or a garage-and-auto body shop–themed bar, but is in fact a former factory. It takes its name from the Knock-Down Door Buck, a kind of pre-fab doorframe invented in 1956 by Samuel Sklar. With 50,000 square feet of interior space in a three-acre industrial lot, the center is a haunting blank slate for the immersive dance theater of Emily Terndrup and Derrick Belcham.

In June of this year, I had the fortune of attending a single, invitation-only performance at the Knockdown Center of another Terndrup-Belcham production, called The Wilder Papers, based on the life of the composer Julian Wilder and the choreographer Dorienne Lee. Dark, haunting, and atmospheric, The Wilder Papers was similar in format to Debut, employing what the creators astutely term a “shifting proscenium,” in which the entire space becomes stage and theater. The Wilder Papers was such a success that Terndrup and Belcham were able to exceed their funding goal for Debut in less than three weeks on Indiegogo.

Debut tells the story of a group of high school students who sneak into an abandoned building on the night of their senior prom. Terndrup choreographed the show in collaboration with the six other dancers, Rebecca Margolick, Emma Judkins, Brendan Duggan, Matthew Ortner, Ross Katen, and TJ Spaur, and co-directed it with Belcham. She is a veteran of Sleep No More, the long-running, Hitchcock-heavy interactive theater show in Chelsea, and that show’s influence can be seen in the experience of attending Debut—“attending,” that is, as opposed to merely watching.

As in The Wilder Papers, audience members follow the dancers throughout the space over the course of the evening performance, each dance “scene” leading seamlessly into the journey to the next, not beginning or ending so much as fading in, then out. The performances overlap with no more announcement than the gradual thinning of the crowd, and the darkened flow of people across the open cement floor to the light and noise of a performance in the corner, or in a small outbuilding, or along the long factory nave. Music pervaded the space, much of it live, spiking the air with a tenuous mood that shifted as easily as a key change.

On entering Debut, the audience gathered in a small rectangular room bounded by curtains and lit by an enormous disco ball. Along one wall was a bowl of bright-red punch (virgin), and paper flowers hung in long strings from the ceiling. The mood was thoroughly mid-70s, but the unofficial uniform for attendees was dark knit layers and functional shoes. After a few moments spent contemplating the punch and scanning the room for acquaintances, a corrugated metal door came down over the entrance, and the show began.

The lights dimmed and a video played at two ends of the room, oblique, soft shots of flashlights, doors being pulled open, almost-kisses by the light of a dance floor. As the video ended, a curtain was pulled aside and we filed slowly into the enormous main room, which was filled with the fog-machine fog of every high school dance. It is the dense, sweet smell of stomach butterflies and done-up hair, of timid sexuality and a bit too much makeup. Our feet crunched across…something—twigs, we thought in the dark. The beams of flashlights cut through the atmosphere, leading the crowd to rows of seats set up facing a rear wall of windows. Throughout the space were lain haphazard, broken bits of furniture, desks and lamps, covered in plastic tarps in a disconcerting stasis of abandonment.

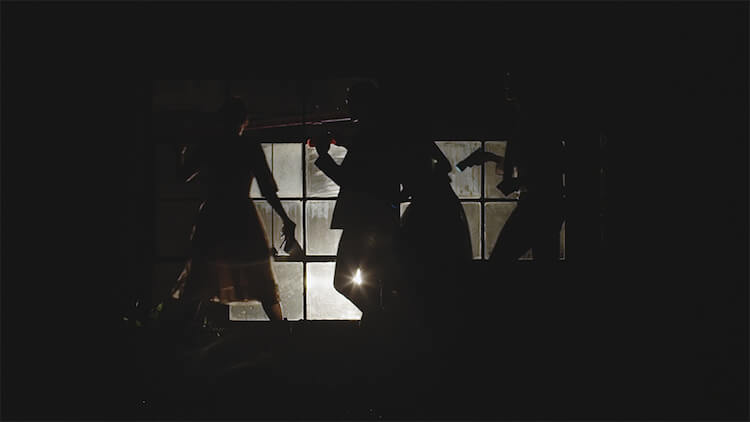

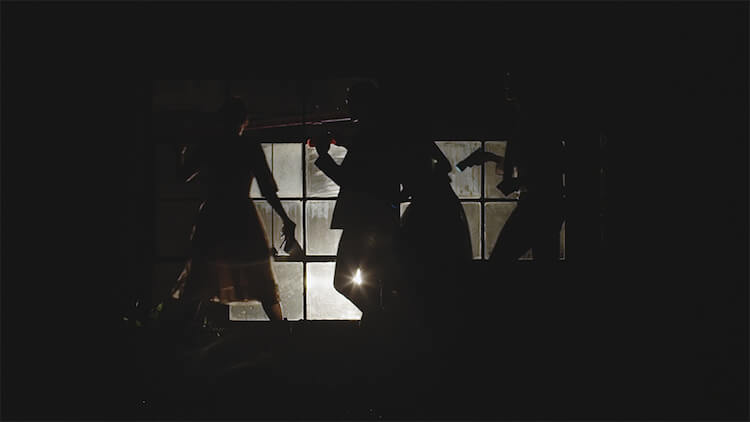

The seven dancers, dressed in promwear, entered from the gravel courtyard around the building through a set of glass doors. They passed bottles of contraband liquor among themselves, lit by a harsh spotlight. In that way that only dance can, their movement began to tell a story in gestures, in emotions made physical—halting, expressive, and deceptively spontaneous. High school boys and girls getting in trouble, drinking in the woods, narrated with the wordless tension of behaving badly together.

From here, the order of things is harder to pinpoint. The night began to feel like a party with no clear center, where in each room is something to see, and if you stay too long in any one place you’ll miss everything. The vignettes the dancers perform are like apparitions, existing for only as long as the crowd is watching; once we turned our backs, they seemed to disappear, and we followed the shifting light like moths. There is little sense of time to the performances, except within the captive space of each room, where the rest of the space seems to fall away. There are no other rooms, for the moment, until a noise reaches us from somewhere in the dark, and we go in search of it.

We stood at the edge of a three-walled room and watched two male dancers roughhouse in that too-drunk way of almost fighting, while a boxy wooden TV set played a black-and-white French film; from there we were drawn into an even smaller room, bisected by an translucent tarp on which the frenetic movements of a soloist played like a shadow puppet, for those who couldn’t squeeze around it to see her. Pulled by the slow movement back to the main space, the room emptied again, and another performance began.

A slow-dance in a foggy spotlight captured the squirmy difficulty of physical closeness, of where to put a hand, whether to kiss, and how, the half-formed intent of teenagers. We watched the crowning and the undoing of the prom queen, the former in a gorgeous, circular video projection ringed by flowers, the latter in the bathroom, in a dizzy, visually arresting dance against a long mirror above a bank of sinks. It felt like being too drunk in public, too drunk for the first time, trying to see yourself in the mirror without the disassociating blur of intoxication.

The finale found us gathered in the main space, the dancers lit by an enormous chandelier that had been invisible in the dark. The dancers ran and spun and caught one another in choreographed chaos, violent and tender in near-equal share, the spectacular, booze-soaked Götterdämmerung of prom night.

Debut was absorbing in its power, its hairpin turns of emotion and orientation, and beautifully delicate in its “shifting proscenium” arrangement. Wandering through the dark, the viewer may feel like a ghost, eagerly peering into the lives of the well-lit living. The show’s atmospheric richness and scenic depth is a hallmark of Terndrup and Belcham’s artistic vision, one we can only hope to see and experience more of, whether at the Knockdown Center or anywhere else they may decide to grace.

Follow John Sherman on Twitter @_john_sherman.

You might also like