Bar Owners Roundtable, Part #1: Talking With the People Behind The City’s Best Beer Bars

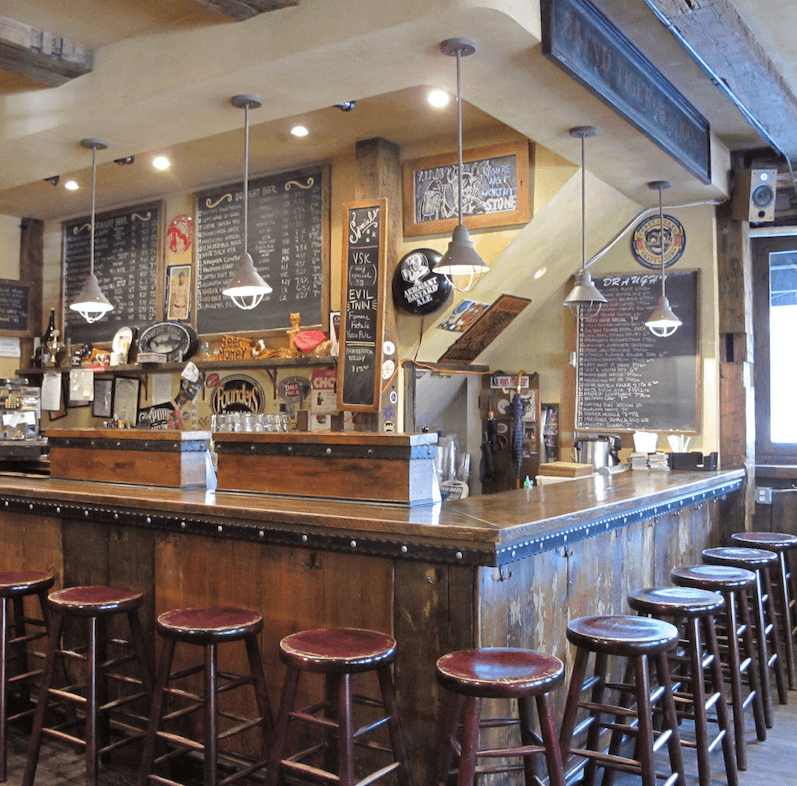

Mission Dolores

Bar Rescue is a trainwreck, but it’s a trainwreck that is strangely and addictingly thirstquenching, one that stirs and shakes grandiosely to serve us an entertaining mix of intrigue, incompetancy, intensity, and inspiration, and always in under 60 minutes; I always return for another.

The show, now in its fourth season on Spike TV, has a simple premise: A proclaimed-by-narrator-constantly “bar and nightlife expert” named Jon Taffer attempts to resuscitate severely mismanaged bars on the brink of extinction by presenting the bar as a battleground. He berates inept owners for their missteps with bulging eyeballs and a glistening integument of perspiration, but also works tirelessly to help fix them. Whether his five-day interventions are successful, whether the show’s definition of success is legitimate, or whether the show is even legitimate, are all unimportant to me. I faithfully watch because every episode is guaranteed to offer the same growly scolding from Taffer, who brilliantly portrays both the villain and the savior. He is a magnetic presence, and I am attracted to the bulging, the glistening. Every episode is a no-fail first-class ride shuttling us around Failuresville—and with the accompaniment of expertly mixed, perfectly poured cocktails!

After saying that, I should probably confess: “Bar Owners Roundtable” will not showcase any bars fit as suitable candidates for TafferAid. This series, instead, will focus on showcasing New York City’s thriving craft-beer bars by interviewing their owners in different sets of four, but always with the same four questions.

Meet David Brodrick of Blind Tiger Ale House; Gerard Leary of One Mile House; Jimmy Carbone of Jimmy’s No. 43; and Ben Wiley of Bar Great Harry, Glorietta Baldy, Mission Dolores, and the Owl Farm. Each has created and maintained a level of excellence for their patrons, executed with an unwavering dedication to serving dope beers—and an avoidance of all wackadoodery. I wanted to know how their bars were born, how their beer menu is compiled and priced, and how difficult it is to operate in New York City, one of the world’s most expensive retail markets. These are their words.

PARTICIPANTS

David Brodrick, Blind Tiger Ale House

Gerard Leary, One Mile House

Jimmy Carbone, Jimmy’s No. 43

Ben Wiley, Bar Great Harry, Glorietta Baldy, Mission Dolores, Owl Farm

One Mile House

I. ON STARTING OUT

David Brodrick: It was 1995 and the only two beer bars in New York City were dba and Mugs Ale House. I hoped and prayed that the Big Apple could support one more, though my friends and family thought I was crazy and that there weren’t enough craft beer drinkers to justify another beer bar in New York. For the Blind Tiger, we took over the One Potato, an old gay bar in the West Village on the corner of 10th Street and Hudson. The previous owner had run it into the ground to the point where you could see into the basement when you were standing behind the bar. I really didn’t know what to do next. A guy I knew from a Hamptons summer share walked by that first day, saw me and asked what I was doing. He said, “You want some help fixing this place up?” Turned out he was a trained architect and contractor. The two of us gutted the place and then rebuilt it, even putting in new floor joists. When I started I could barely hold a hammer, but after working seven days a week, 16 hours a day, I knew every nail in that place personally. We never got any building permits. I didn’t even know the city had a Department of Buildings, which was probably a good thing. I only had a $100,000 budget for the whole project, and I wound up going $35,000 over, which completely freaked out my investors. We were screwing the front door on when the first people showed up for opening night. When the bar started filling up after about a month, I realized the city could definitely support three beer bars.

Gerard Leary: I remember meeting my sister at Monk’s Cafe in Philly when I was 19 for a happy hour. I had a great fake ID but a horrible taste in beer. All my sister’s co-workers were talking about this great beer called Duvel. 8.5% ABV? Sign me up! My interest in beer literally started at that moment. I moved to DC when I was 21 and used to frequent the Brickskeller. I really got to know the international brands at that place and realized that I wanted to go down that rabbit hole and find new and interesting beer. Then I worked at Stout on 33rd Street after moving to New York City and really got taught the business side of running a bar there. When the opportunity to open One Mile House came about, I knew I wanted to focus on beer. Opening a bar is a crazy mix of emotions. You’re excited about your new ideas, but you worry about them working. You stress about training your staff and all those moving parts in play. Then, add to the fact that you have partners and the financial responsibility to the people that put their savings into something that you personally believe in. The most important thing is the responsibility to each guest that walks in and decides that your place is the place they will spend their money at. I think after almost three years since I opened One Mile, the place is completely different in a good way. If you are open to learning and are not afraid to try things I think you can really give your guests something special.

Jimmy Carbone: I opened my first restaurant, Mugsy’s Chow Chow, in the East Village in 1994. I had an interest in wine, which naturally led me to the top beer and spirits people. Around that time, Brooklyn Brewery also acted as a distributor of top craft and specialty import beers like Chimay, Rogue, and Schneider. In 2005, I found an old ukrainian speakeasy basement on East 7th Street. It had been the epicenter of craft beer in New York City in the 80’s: upstairs at Burp Castle and Brewski’s, now Standings, the first New York City Homebrewer’s Guild meetings were held. Garrett Oliver was first tasting people on his beer, where he met Steve Hindy. The rest is history. The space had a beer-only license so I considered the options and took the leap, opening initially with just that. “Drink good stuff” was Ray Deter’s motto at dba—we opened around the same time. The first year, I had many people asking for Stella, so I always carried a specialty Belgian pilsner, at the time Strubbe pils. I also had a Guinness substitute, and a constant Chimay Triple line. Sixpoint was new at the time and it was another reason I felt confident opening with a beer-only license. For the first time in years, there was a new brewery in New York City that not only made good beer, but customers were excited to find it and drink it! So we had two or three lines of Sixpoint for the first few years.

Ben Wiley: About eight or nine years ago, there wasn’t a beer bar on Smith Street. Everything was sports, or gimmicky, or too neighborhoody. No one was selling curated next-level shit, and my brothers and I thought this was what we could bring to the area with Bar Great Harry. I had gotten very into beer over the prior five or six years—I fell in love with fermentation and bread-making first, went to culinary school and cooked in pastry in various professional kitchens—all the while drinking craft beer at home literally nightly. We hatched our business model on napkins in our apartment we shared on Court Street. When we opened Harry, we immediately lived it. We were there all the time. For the next 3 bars: some of it gets easier—the contacts, the purveyors, the sub-contractors, all that shit—because you already know a lot of them. But balancing personnel gets tougher, being everywhere at once gets tougher, gauging different area’s customers’ wants gets tougher, differentiating yourself gets tougher.

II. CHOOSING YOUR BEER MENU

DB: The beer we pour first and foremost has to be something I want to drink. If it isn’t good enough for me, I’m not about to make my customers drink it. I also like to support breweries owned by beer people, meaning people who are truly into the craft of making beer above all else, with the bottom line a secondary priority. I also like breweries that have a real vision for what they want to do, or a new angle—in a way, their beer literally has a voice. I think that comes from my journalism days, which I studied before opening anything. Lastly: At the Tiger, our goal is to create an overall experience that isn’t dependent on having the latest and greatest keg or bottle. When you leave, we want you to talk about our place, not necessarily a particular beer you had.

GL: This is by far the best thing about my job! I always say putting together a great tap list is like the adult version of collecting baseball cards. You want your rare heavy hitters but you also collect your favorites. To me, outside of events, balance is most important. Having a good variety of styles and not being too heavy on one particular style is key. Staying true to the season. Having a couple extra saisons in the warmer months and a few extra stouts in the colder months is always a good idea. With that being said, don’t abandon the latter style of the season. Finally, listen to your customers. There’s always something out there that you’ve never heard of. Some of the best surprises came at the recommendation of a regular.

JC: Our beer lineup is always changing. When I first opened in 2005, I had nine of the 12 lines as specialty European imports. The other three lines were Sixpoint. Within a year or two, the demand for American craft beer grew. Three or four years ago, we gave more of our lines to New York City and regional craft breweries. It’s crazy now, though: There is always something new, always a style that people are bringing back. Right now, I have these various styles all fighting for draft lines: sours, ciders, good pilsners, big hoppy IPAs, fresh hop IPAs, a range of dark beers for fall, and so on. I love it. It’s the golden era of beer.

BW: Each bar is a little different but generally each line is a genre of beer. If you have 12 lines, it’s easy that way. If you’ve 30 lines, you can be more creative, doubling up on some genres. We listen to customers a lot, really. Everyone says that, but we really do. We are always trying to find that balance between curating and leading people in a direction, and then listening to folks and giving them what they want.

Jimmy’s No. 43

III. PRICING YOUR BEER

DB: We follow a formula for pricing as much as possible, keeping our beverage costs at 25%, which is the industry standard. With some kegs you can’t do that, they’re just too expensive, so we eat it a little on those, but if the beer is great, we look at it as a promotion. We try to keep our prices under $10 a glass, though the size of the glass might be smaller. I have no problem with putting a $9.50 price tag on an eight-ounce glass if the beer is worth it. I’ve paid a lot more than that for glasses of wine that weren’t worth it.

GL: I have a formula that I follow. It breaks everything down to a percentage and I try to get as close to a particular number as possible. As a bar we make the biggest markup on the product itself but being in New York City, you have large overheads and need to charge accordingly. Morally, I try not to charge anything over $9 a pour. Some beers like KBS, Parabola, or Bourbon County, you just don’t have a choice. In that case your customers know how much that beer costs and don’t mind shelling out a little more for quality. Sierra Nevada’s Pale Ale is a benchmark pale ale and I do pour it every once in a while but that’s not what people travel to my bar for. Having something new and interesting that someone hasn’t had before is what really gets people going at my place.

JC: Depends. We topped out our pints at $8. Some goblets we’ll go up to $10. Pricing is tricky. Our base costs—rent, fees, and insurance—have gone up three or four times since 1998, but the prices we can charge for beer aren’t that much higher.

BW: Pricing is tougher now than when we started, for sure. Beer costs a lot now. Without going into numbers, frankly bars in New York City just don’t make as much margin as they used to. Fact. Some customers in some areas will pay $1/ounce for esoteric draft beer, yeah, but in some areas people won’t. Bars just don’t make good profit on certain beers. But you know what, that’s our choice. I’m not complaining at all. We CHOOSE to sell what we do. We know what it costs. We know when we’re selling it to just feature a cool beer, to make people happy, or to establish connections with the producer.

Glorietta Baldy

IV. OPERATING A BEER BAR IN NYC

DB: With rents the way the are, it’s getting tougher and tougher to make money. When our 10-year lease ran out on the first Blind Tiger, we lost our space to a Starbucks. They were willing to pay double our rent, and it’s a lot worse out there now. And when we moved to our current location on Bleecker and Jones, the whole project cost almost 10 times more than the original. I would say our biggest challenges are shrinking margins, incredible competition, and keeping our concept fresh. New York is a city that keeps you on your toes, no matter how long you’ve been around. You have to keep up, you have to be ready for curveballs. It’s gone from three beer bars in early 1996 to almost 100 now. With more on the way, I’m sure. Everyone wants to be in New York City, and you have to compete with chain stores that don’t even have to be profitable. That’s tough.

GL: This is a city where a nickel cost a dime. The cost of doing business here is huge. Rents are some of the highest in the country, taxes, multiple city departments with their hands out, labor costs, and just straightup maintenance on your bar can all add up to large overheads; but the rewards are just as large. Some of the greatest minds in the restaurant world reside and succeed here. If you’re not motivated by that, then you don’t belong in the game. It’s one of the only cities that if you don’t know something, there are 100 people doing it better then most. Keep your eyes and ears open and learn. Also: The hardest part of opening a place here is being part of the hype. Some people pay for it, some create their own, and some just sit back and hope to be judged on what they do. There’s no right way, but being able to step out in front and be noticed among litterally thousands of bars is an amazing feat. After that, I think it’s up to you.

JC: There are a ton more places to get a good IPA or other craft beer. Many cafes, restaurants, and local bars will offer at least one quality selection. New York City is always changing. There can be ruinous competition. Just when you’ve established yourself, everyone realizes you have a good idea and you’ve already created the roadmap. No matter what the rent, bars sell one beer or cocktail or plate of food at a time. Margins are tight, but I’m in this for the love of hospitality and good beer. Period.

BW: In NYC, there’s loads of good quality bars, so the market is crowded. You gotta stay conservative in expenses and costs to be successful. This is old school basic shit but keep your nut low and you’ll get by—maybe you’ll even make a few bucks once you get in good habits. You gotta treat people well. Talk to bartenders and they’ve all worked for boneheads. Differentiate yourself by treating everyone like you wanna be treated and sell at a respectful price to people so you make yours, yeah, but so the customer doesn’t feel fucked. Everyone else in your operation has gotta be happy and content before you are. Then, you’ll wake up one day and be like “Holy shit this is actually working, I’m not getting robbed blind, people hang out and drink, and we’re making money!” The scene has drastically changed in the eight years owning bars with my brothers. There are loads of good bars but there are also loads of good, quality-seeking customers, so I like to think that a rising tide raises all ships and there is plenty of room for all of us bar owners to work hard and be successful.

You might also like