James Franco Just Likes to Watch

Despite our best efforts to the contrary, we continue to have to pay attention to James Franco. After the close of his Broadway run of Of Mice and Men, the New York Times published a brief profile of him last weekend, in which it was revealed that he is sharing an apartment this summer with his frequent collaborator and avowed BFF, Scott Haze. Gawker called out this bit of news on Wednesday, with eyebrows raised, to which Franco responded first with a screenshot of the Gawker headline, and then with a series of elaborate stunt kisses and scribbled-on photos, calling out Gawker and other sites for capitalizing on what he called a “homophobic scoop.” But what about the moral grayness of publicly playing gay to make a sarcastic point?

For their part, Gawker backed up their raised eyebrows with yet more raised eyebrows.

I probably wouldn’t care so much—or at all—were it not for his near-constant involvement in films and other projects that turn heavily on the gay experience, nearly to the point of obsession. In the past decade or so, Franco has written, directed, or starred in at least six such films—seven, if you count James Dean, from 2001. The others include Milk (2008), Howl (2010), The Broken Tower (2011), Sal (2011), Interior. Leather Bar. (2013), and the forthcoming Michael, about a gay activist who renounces his homosexuality and becomes an antigay pastor. Franco also wrote and directed The Feast of Stephen (2009) and The Clerk’s Tale (2010), two short films that deal with gay characters, identity, and self-expression.

To hear him tell it, Franco’s interest in gay characters lies in broadening the palette of stories told in mainstream American culture. And while this is sort of a sweet thing to want to do, notionally, it’s exactly the sort of blinkered, Macklemorian advocacy that champions gay voices while at the same time denying that they might be heard without the angel investment of a Concerned Ally. Allies are and have been a vital part of the fight for gay rights, as well as for gay representation in film and television, and I certainly don’t mean to discount their importance. But where allies amplify the voices that already exist, Franco talks over them with his own.

Interior. Leather Bar. is Franco’s bizarre meta-mockumentary about remaking 40 minutes of cutting-room-floor pornographic footage from Cruising (1980), which starred Al Pacino. Franco was inspired to reclaim this footage, he says at its beginning, after reading Michael Warner’s 2000 book The Trouble with Normal: Sex, Politics, and the Ethics of Queer Life, which argues that normalizing homosexuality with institutions like marriage will rob the gay lifestyle of its radical sexual autonomy. It’s an interesting theory, and one that lives within the idea that homosexuality should remain always at odds with the mainstream (read: heteronormative) culture. Franco claims this as his jumping-off point in the first ten minutes, yet by the last twenty he is exhorting his star, Val Lauren (played by Val Lauren) to “put [gay sex] in the fuckin’ mainstream!” So who knows.

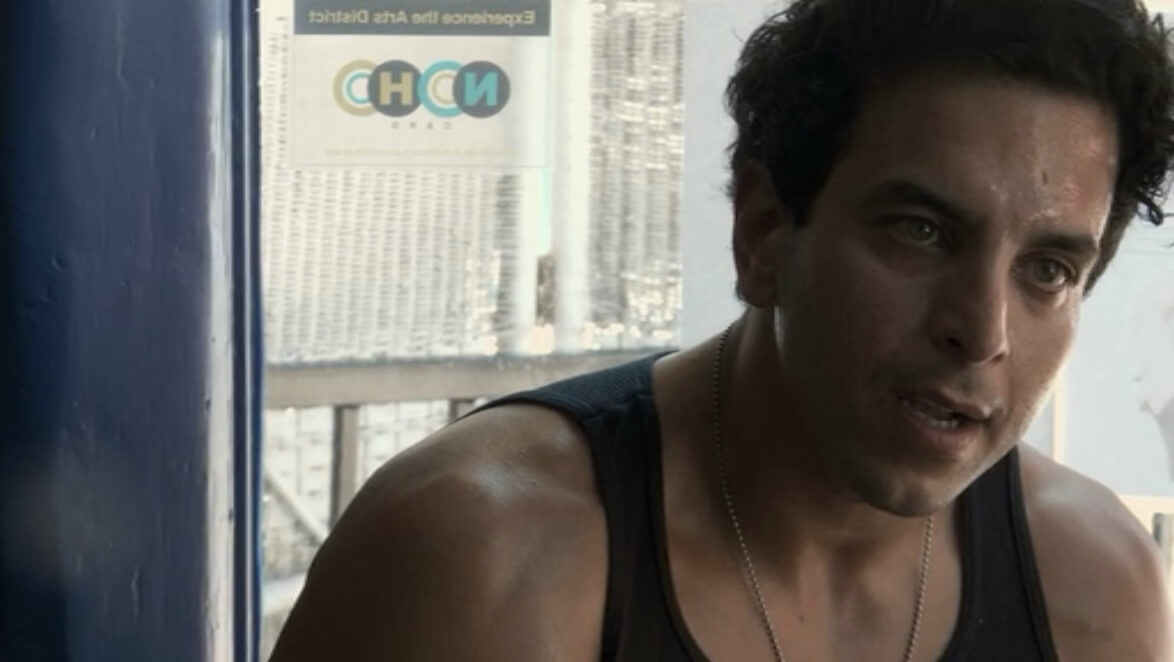

In many ways, Interior. Leather Bar. is a straight man’s fantasy of gay sexuality—raw, uninhibited, and, most of all, shocking! Franco plays himself, as director-visionary–homosexual apologist, and the precise distance between Franco and Franco-playing-Franco is not often clear. The same line is blurred with Val Lauren’s Val Lauren. Film Franco delights in Film Lauren’s shock in witnessing a real live gay S&M sex act during filming, as it affords him the chance to denounce the heteronormative patriarchy, and open Lauren’s eyes to what it’s made him believe. Lauren makes the following face:

“That’s beautiful and attractive?”

That Franco’s gaytopian vision is a leather bar in 1980 exemplifies the almost Orientalist view of gay life that the most fervent and vocal heterosexual homophiles often have: Men cruising the Ramble in Central Park, rioting at the Stonewall, or living free and easy at the Pines. (The same thing happens to all minority cultures in blockbuster films—they are either not seen at all, or seen in the same context over and over again.) Franco’s homosexuals—Hart Crane, Alan Ginsberg, Sal Mineo, Scott Smith—are historical, frozen in time. They are oppressed lovers and noble dreamers, tragic figures whom Franco unleashes with his broad-minded, sensitive artistic vision. Many gay men share this potted nostalgia, but they recognize that there is a gay present, too.

Last year, after his Comedy Central roast, Franco declared that all the gay jokes made at his expense didn’t bother him at all. In fact, he said, he wishes he were gay. It’s a strange thing to say, as a straight man. It’s the sort of comment that has the blush of post-modern masculinity, the sort unconcerned with proving itself, but which has underlying it insurmountable privilege. The straight privilege required to say “I wish I were gay” is as all-consuming as the white privilege that would be required to say “I wish I were Black.” Homosexuality must be an exotic, less privileged Other in order for Franco to play out his privileged interest in it, and in order for that interest to appear as the product of an enlightened mind rather than of a voyeur.

This apparent enlightenment comes from the darkly drawn boundaries around heterosexual male comfort zones. The film within the film of Interior. Leather Bar. casts both gay and straight actors in gay roles—roles originally played by gay extras in Cruising, who were simply patrons of the various bars where scenes were filmed—and the straight actors spend a great deal of time discussing “how far” they would “go” on camera with another man, and what degree of physical contact they’re comfortable with. These conversations might as easily have been overheard backstage of an eleventh-grade production of Angels in America.

The palpable heterosexual discomfort with other men’s bodies frames the challenge of playing gay as a series of ever-lengthening bridges to cross—kissing, but no tongue; tongue, but no nudity; and so on—such that the “further” one goes, the better, the more sensitive, the more luminary an actor one is. Or so Franco would have it. (There is no such lauding of gay actors who play straight—that is, if they are invited to.)

Interior. Leather Bar. is a rare occasion in which Franco does not play gay but merely directs it, walking a handheld camera in circles around two actors having sex. It is the height of voyeurism, assembling as he has the entire film for some more-sexually-liberated-than-thou social statement. Whether or not Franco is gay is uninteresting, except with respect to the liberty he takes in telling gay stories.

There’s a scene in Cruising in which Al Pacino’s character, undercover, wears a yellow handkerchief in his left rear pocket—indicating an interest in “watersports.” A man with a matching yellow hanky approaches him. “Are you into watersports?” he asks. Pacino brushes him off, saying, “No, I just… I like to watch.” Leaving, the man says, “If you like to watch, then take that hanky out of your pocket, asshole.”

James Franco likes to watch, and to be watched. Fashioning himself the creator and star of an oeuvre of gay biopics may be an attempt to atone for his privilege, apparently recently discovered, or maybe he earnestly believes cultural appropriation is a matter of benevolent artistic license. Or, maybe, he’s just an asshole, at a bar he doesn’t belong in, claiming just to like to watch.

You might also like